How COVID-19 Suddenly Halted Music, and What May Be Next

COVID-19, the terrifyingly asymptomatic virus that's killed more than 100,000 Americans, stopped the music industry in its tracks two months ago. At first, however, the threat ran parallel to business as usual.

Chinese media reported the first-known death caused by the novel coronavirus on Jan. 11. Styx were finishing a two-date stand that night at the Celebrity Theatre in Phoenix. Elton John was beginning a run of shows at Australia's Hope Estate.

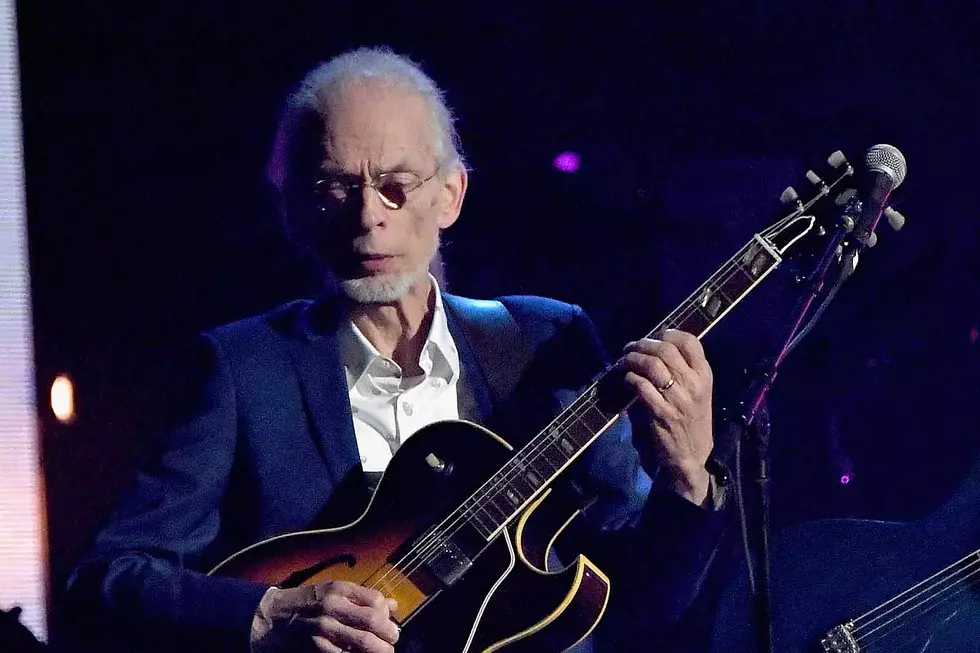

The first confirmed U.S. case followed on Jan. 21 in Washington state, as a man developed symptoms after a trip to Wuhan, the epicenter of the Chinese outbreak. Yes announced that Alan Parsons would take part in a series of pre-Cruise to the Edge dates later in the day. Tours by Alice Cooper and Hall and Oates were also announced.

By Jan. 31, the World Health Organization had declared a "public health emergency of international concern," as Tool's tour in support of Fear Inoculum reached Memphis. The disease caused by the novel coronavirus was given a name, COVID-19, on Feb. 11. Meanwhile, Gov. Henry McMaster officially declared it Kiss Day in South Carolina.

The first reported U.S. death arrived on Feb. 29, but rock fans were still more focused on Australia, where widespread wildfires prompted an all-star benefit concert featuring Queen + Adam Lambert, among others.

The music industry finally awoke to the looming threat, just prior to President Trump's declaration of a national emergency on March 13. Concert promoters Live Nation and AEG suspended all dates for March the day before. Yes had already pulled out of their scheduled performances; the Who, Kiss and Lynyrd Skynyrd quickly followed.

Doctors were warning fans that close contact in enclosed places, both of which were unavoidable in concert situations, was a principal risk factor in the spread of this disease. At the same time, contact tracing tens of thousands of concertgoers from each show would prove extremely difficult if not impossible.

Yet, there were those who continued to hold out hope against the pandemic. Guns N' Roses subsequently played a festival date, appearing March 14 at Vive Latino in Mexico City. Nikki Sixx encouraged fans to "dampen down the hysteria" a day later.

Watch Elton John Perform During 'One World: Together at Home'

That's perhaps understandable, with so much early confusion about the virus – and so much on the line. The music business is powered by live events in the streaming age, and shows had turned into a seemingly endless money-making machine. The concert trade publication Pollstar was again predicting record ticket sales based on first-quarter ticket sales.

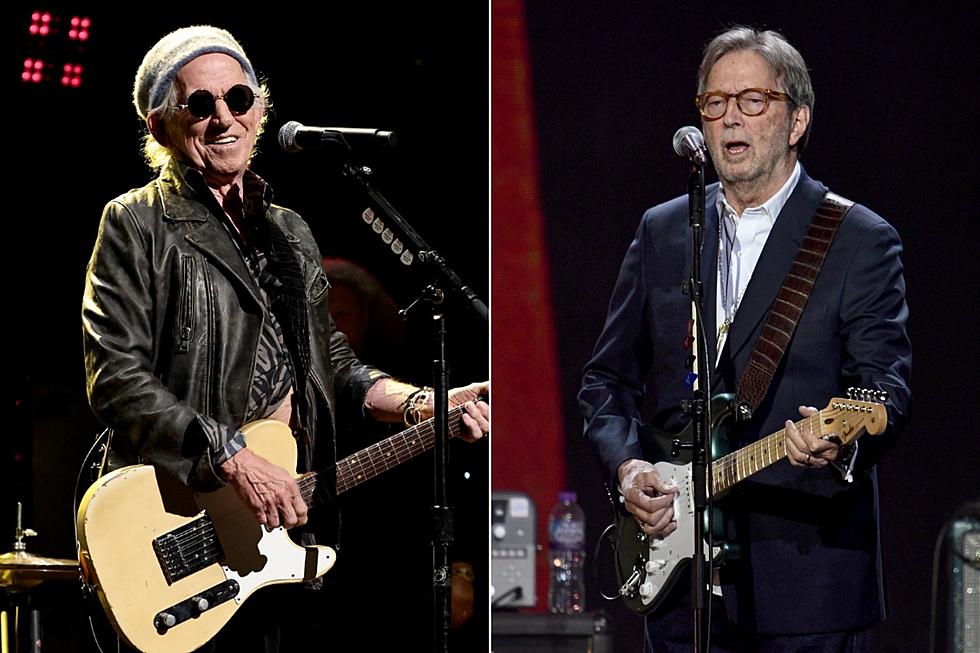

By the following week, however, the scope of this health crisis had become more clear: Guns N' Roses pushed back their South American dates until November. Rolling Stones shows were delayed indefinitely on March 17, as Ozzy Osbourne producer Andrew Watt was diagnosed with COVID-19.

Everything then ground to a sudden and nearly complete halt as quarantines became widespread. Even some new albums, including those from Nick Mason and Dennis DeYoung, were initially put off. Music sales bottomed out. Musicians like Geddy Lee, Paul Stanley and Rob Halford began urging people to stay home.

Nevertheless, the United States was taking the lead in a very grim race: By March 26, no other country in the world had more confirmed cases. Cancellations became a drumbeat, until the concert trail was deserted. As fans waited out the worst of it, rockers' homemade lockdown videos emerged as viral hits, then livestreams and virtual concerts became the norm in April.

Live Nation worked feverishly to develop a new refunding process for thousands of frustrated ticket holders. In a sign of the times, empty streets gave municipal workers a chance to repaint the famous crossing at Abbey Road.

The economic impact of all this was immediate: Ticketmaster furloughed a quarter of its employees, as surveys showed most concertgoers wouldn't buy tickets before a cure for COVID-19 was discovered. But experts said finding a working vaccine could take a year or perhaps much more. As unemployment spiraled toward 40 million claims, states began re-opening in piecemeal fashion – and so did local elements of the music industry.

Other glimmers of normality emerged. Pearl Jam released a long-awaited new studio album; Bob Dylan put out an epic new song. The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame announced a rescheduled November date for the previously postponed induction ceremony.

Watch the Doobie Brothers Perform 'Black Water' While in Isolation

Still, by then, Jackson Browne and Bon Jovi's David Bryan had also tested positive. COVID-19 wasn't going away. Talk turned to how technology might help live music survive, and the idea of drive-in concerts was floated. One enterprising promoter organized an early show based on social-distancing guidelines, setting a standard that could be followed moving forward.

June was set to dawn with some smaller live-music venues open, while others remained shuttered – depending on the state where you lived. No major tour had resumed. In fact, Guns N' Roses hadn't even confirmed when their postponed North American dates would take place. Joan Jett admitted she was "not comfortable" with the idea of playing stadiums amid the pandemic, creating a potential snag in Motley Crue's reunion tour.

Reported coronavirus cases topped 5 million worldwide the same day. Nearly all of the remaining holdouts relented, as bands like Steely Dan and the Doobie Brothers finally canceled or postponed.

What's next? Good answers about the future remained hard to come by, despite growing plans to reopen the country. Some experts suggest that live music might not fully return for many months, perhaps not before 2021.

"I can't imagine that happening until we have a vaccine," Travis Rieder, a research scholar at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics, told USA Today in early May. "The risk of those events as we would have done them in the past outweighs the benefit of doing them. We are flexible creatures. We're going to have to do things differently."

The question, of course, is how. Uncertainty about safely conducting large-group events like concerts and music festivals could actually end up making them one of the last parts of every-day life that returns to normal, Peter Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes, told CNBC.

Meanwhile, Pollstar predicted the concert industry could lose almost $9 billion in 2020.

More From Ultimate Classic Rock