Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason on ‘The Early Years’ Box Set and More: Exclusive Interview

Pink Floyd's mammoth 27-disc box set, The Early Years 1965-1972, allows die-hard fans to immerse themselves in the band's history with more than 11 hours of audio, 14 hours of video and five hours of rare concert footage. The collection, released in Nov. 2016, spans the era from when Syd Barrett, Roger Waters, Richard (Rick) Wright and Nick Mason formed the band through Barrett's exit, when David Gilmour became a member.

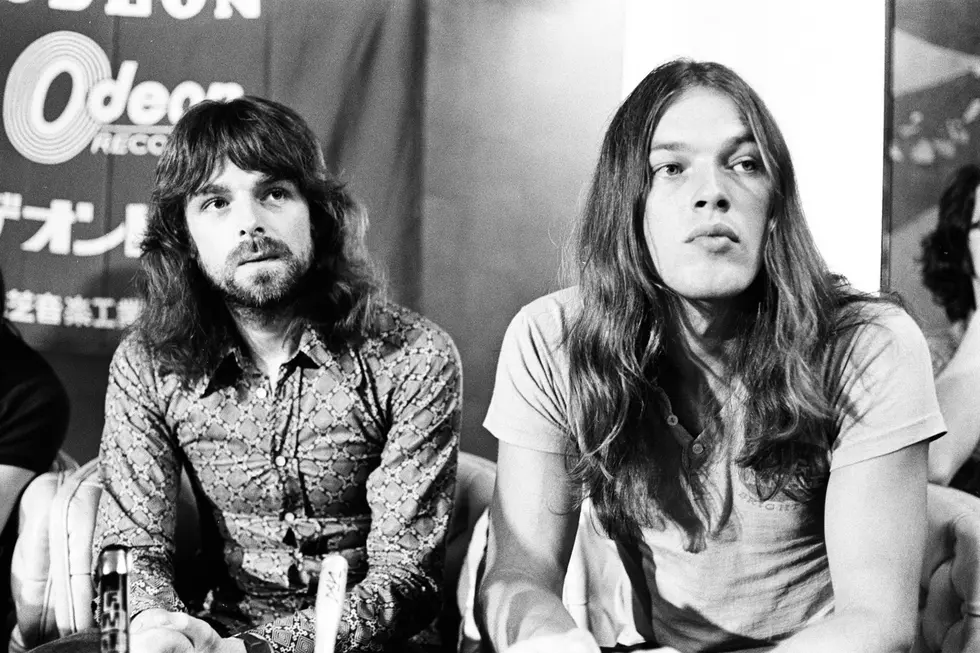

Mason, the band's drummer, talked with Ultimate Classic Rock in New York about recording and performing the music of Pink Floyd's formative years that would lead to the 1973 release of their mega-hit, The Dark Side of the Moon.

If Syd hadn't had health problems and remained with the band, what musical direction would you have taken?

Very hard to answer because, I mean, it's theory of chaos, it could have gone in a million different directions. It's fairly easy to say we'd continue along this sort of pastoral, slightly quirky English thing like "The Gnome," "Scarecrow." But actually Syd was absolutely instrumental in "Astronomy Domine," "Interstellar Overdrive." So we might have continued down that road as well. What would have happened with Roger if he turned into the songwriter he became, or would he have ended up held back because Syd had established himself as the major writer? Maybe it would have lasted two years and that would have been it. Maybe we never would. I can't see Syd leading on Dark Side, maybe that's perhaps the way to put it. It would have come to some sort of end.

What songs did you think went unappreciated by fans at the time?

It's difficult to say because there's a whole swath of early tracks that are missed by an audience that we think started at Dark Side of the Moon. That's the problem because we actually changed from being a slightly underground band to – I won't say overnight – but that one album pushed us suddenly into a whole new world. The interesting thing is that quite a lot of particularly younger people who discovered Dark Side don't look backwards, they look: "What did they do next?" So I suppose I'd say the album that I'm particularly fond of is A Saucerful of Secrets because I think you get a transition from Syd and you almost get a wonderful goodbye from Syd with "Jugband Blues."

Tell me about recording "Jugband Blues."

The interesting thing with "Jugband Blues" was at which point did Syd feel that he really had to have that silver band, the brass section? The stage that we were recording those songs, the songs that never got released, I think Syd was almost deliberately looking to just upset things. Looking back on it now I think he wanted out and he didn't really know how to achieve that and so it was wanting the brass section and getting me to sing on some other tracks and things like that. All of which were part of a "let's throw everything up in the air." I think that because of the way that the silver band works, it's really sort of touching, a really sad element to the piece. I think really strong, a wonderful goodbye from Syd. Unexpected too.

At the time, did you think "Arnold Layne" was the best choice for the first single?

Yeah, I did. I think I was totally taken aback when the BBC banned it. It really didn't seem like a salacious or difficult record. And the bizarre thing was that it's almost as though someone said to someone at the BBC, "Well, you know what this is about." Because what was learnt from that was don't ever explain things to the BBC. Six or nine months later they were playing "Walk on the Wild Side." Which is absolutely about a world that the BBC – they would have banned it like a shot if someone had just said, "You know what this is about." So it was really peculiar but I thought the record, I still listen to it now and think it sort of sounds like a perfectly good single from the period.

The follow-up, "See Emily Play," brought more success. How did things change for the band at the time?

With "See Emily Play" we were on Top of the Pops; our agents could then advertise us as "as seen on television." We were sort of, I won't say established but we had a record, which meant we could work constantly. Which was very good for our playing. And was what we wanted to do. The problem was that our repertoire only included "Arnold Layne" and "See Emily Play" and a couple of other Syd songs. The rest of it was improvisation and of no interest to a lot of the audiences in the North of England who wanted soul bands. At the time, soul band was king. I remember doing a show – one show – where we were fourth or fifth on the bill. And the other people on the bill was Cream and it was Jimi Hendrix. And neither of them were top of the bill. Top of the bill was a band called Geno Washington & the Ram Jam Band, who played Otis Redding hits. They were a cover band of American soul music. And so when we went off to play to these sorts of people, they were really unenthusiastic [Laughs].

What did David's arrival bring to the band?

It brought all sorts of things. Stability, I think. The interesting thing was, it didn't immediately bring in a replacement songwriter, which is one of the things we should have thought we needed. But the stability of David, he was both a great guitar player, and great singer. You know I'm still surprised how we just were so relieved when Syd went. We could just get on – even though we were playing his repertoire, mainly, we really enjoyed it. And I look back on that and I just think, it was such a relief. And just the feeling that we can get in the van and go off and play and enjoy ourselves, do what we really wanted to do, which was to play this music. So he was a savior in a way. I wouldn't say that to his face because he's conceited. But he was the perfect solution.

As Roger took a greater role in the lyrics and the music became more complex, how did your percussion work develop?

Well, I think it just kept abreast of what was happening. The interesting thing is that I played the drums but I hardly played at all before we had turned professional. As soon as we did then suddenly I was playing every day instead of once a week. I think that's true of most of us, Roger's playing as well, and Rick's probably. We just all developed together. The nice thing was that I can't remember really ever any of us telling each other how to play or what to play. We would almost always accept, more or less, what we did as individuals. So no one went, "Nick, I don't think you should do it like that, you should do it like this." And I don't think anyone ever said that to Roger or to David or to Richard.

Is that unusual?

Yeah, I think someone would bring a song in and then allow the others to interpret it. Normally either there's a particularly assertive songwriter or there's a fairly assertive producer and we certainly avoided certain producers until we got to The Wall, really. And even then, that's the first time I can remember actually sitting down with someone and talking about what the drum parts should be and how it should work.

Was that the period that you started bringing in other percussion instruments?

No, we brought in other percussion instruments whenever they were available. One of the things about working at Abbey Road was that quite often because there were sessions going in and out all the time, you'd arrive in the studios and find that someone had left a bunch of equipment there which was to be picked up by the rental company. So there might be tubular bells, there might be tuned tympani and there might be rototoms. The rototoms were just by chance, the day we were working on one of the Dark Side tracks and they'd been left in the studio, for collection, and we'd found them and just set them up and thought, "Oh, these are good." Did the intro for "Time" but by the time we came back after dinner, they were gone again, so there was no retake [Laughs].

How did "Careful With That Axe, Eugene" evolve over time?

The first version, I think, was done as a B-side for a single and it was just that octave thing that Roger played and Rick warbling along. It evolved because we'd almost immediately took it out and played it live. Once we did that, it moved from being two-and-a-half minutes to about five and then to seven or whatever. If we had an idea, or it was something that we liked playing extended, we'd extend it until we actually thought either the audience was bored or we were.

You've said that at that time, you wanted to be rock 'n' roll stars and make singles. How did you decide that you would become an album-oriented band?

The real simple answer to that is we didn't decide, the public decided for us because they stopped buying the singles. We released two or three singles after "Emily" and they were of no interest. They didn't sell, simply. I think we then announced rather grandly that we were an album band. But by that time Sgt. Pepper's had established the fact that albums were the new big thing. We have a huge debt of gratitude to the Beatles because it transformed the relationship with the record company, who stopped trying to make us make singles and more or less said, get on with it. And it gave us far more studio time and far more opportunity to work on different ideas and so on. That was about the time of "Point Me at the Sky" and "Paint Box" and so on.

You've said that the most significant show on your 1970 tour was a few blocks from here at the Fillmore East. What happened there?

It was one of those things [Laughs] that we never quite got right. There was the thing of being in the band room and the usual thing, we hadn't really worked out, was what other musicians looked like and who was who. There were these people who sort of wandered into the band room and we were rather anxious to get rid of them, thinking who are these people, are they sort of off the street? And only found out afterwards that it was the Band. And we were all huge fans of them. I mean, Music From Big Pink was one of the albums that we all owned and had all bought in America. It's one of those things that 45 years later we're a little bit embarrassed about it.

You've written that roadies often created problems for the band in those years.

The sort of classic roadie is almost a thing of the past. They've been replaced by techs. I used to have a drum roadie. And it's the same guy but he's now a drum tech. It was probably what it was like sailing in the Navy in the 18th century. You had this crew who if released on shore were really a frightening thought. They had to be collected by a press gang later on. I think that so often, the roadies had the wild life and the band would really be back at the hotel having hot chocolate.

What were the challenges in recording Atom Heart Mother?

The biggest challenge was that there was a directive from on high that we use two-inch tape, which recently arrived, these multi-track machines. It was not to be edited, not to be cut. Because no one knew whether there'd be recurring problems with that and whether it would maybe break or distort. That meant that Roger and I had to play the entire backing track from beginning to end in one take. And neither of us liked click tracks. So we just embarked on this pretty monumental journey to do 23 minutes. We probably broke down twice and had to do it again, but I have to say, when I listen back to it, I can definitely tell when I'm beginning to get a bit tired and sort of get on again.

It's no secret that Pink Floyd's music is often played by stoned fans who want to enhance the experience. Is that considered at any time when you're in the recording studio?

I don't think so. The reason I say that is because if I was trying to describe how things are done in the studio – it's very selfish. The record is nearly always made entirely to please ourselves. We are the arbiters of what we think is great. We very rarely go, "Our public will like this." Because I think second-guessing what the public will actually like is impossible. There are a few people who could do it – maybe a Phil Spector but it's certainly not a skill we ever had. And what you end up with is, if you please yourself, then that seems to work. Then people like it. But start going, "Oh, let's put this in because there'll be a load of stoned hippies who will go, 'Ooh, what's that? Man! It's going backwards!' … If we did even do that it would be said in jest. To try and actually tailor your work to the man who's just done a big reefer is a bridge too far.

How were you able to expand your experimentation with sound on Meddle?

I think because we had more or less unlimited studio time when we were making Meddle, we certainly spent time not so much experimenting – we didn't embrace new technology. I think the Moog might have just about have been beginning to surface about then. What we did do was fiddle with the stuff we already had. So we did quite a lot of things with miking up Leslie speakers. That sort of sound that came from nowhere. Rick hitting the note but then feeding it through the Leslie speaker and then putting a mic on maybe two sides of the Leslie speaker so we got this stereo thing – which sounds exactly like working for those stoned hippies but wasn't. I suppose it's just that thing of going "what if" – what if we plug in the other way around? What if we put the microphone over here? What if we do that? So it wasn't very scientific but it was quite experimental.

A few years later you released Animals. Do you think it got the appreciation it deserved?

I think it got the appreciation it deserved. I think it's a record that maybe would benefit from revisiting, perhaps for the mixing of it. I'm sure David and Roger at times mentioned it as the one album that might possibly be looked at again for a remix. And partly because we've probably still got the multitracks, so it'd be relatively easy to do it. But also because technically it didn't have the advantages of an Abbey Road crew doing it. And Brian Humphries is a very good engineer but we were using slightly less glamorous equipment. We were using the MCI machine, which was perfectly serviceable. When we started on The Wall demos with the same machinery, it was very quickly shifted out by our producer James Guthrie in favor of slightly more elaborate, slightly more expensive equipment. So it's technically a little bit flawed. But in terms of public acceptance or knowledge of it I think it's quite a lot to suggest that people haven't taken some piece of work seriously enough or given it enough attention. Because I think that's for them to decide. It sounds a bit pompous really to say. The interesting thing with Animals is how it collided with the punk revolution. I believe the album is just that little bit rawer because that was the time that it was developed. And prog-rock was becoming so overblown at that given time. We were not cutting edge anymore. We'd become maybe a bit mainstream.

You've written that you were determined not to become one of those overblown prog-rock bands but you didn't mention any names.

First of all, everyone was beginning to go in toward an orchestral array. Yes – Rick [Wakeman] was definitely loading up with orchestral blurs. But I think ELP [Emerson, Lake and Palmer] were going out, I remember Carl [Palmer] had this sort of handmade Indian carpet that his drum kit was arranged on. It was beginning to feel that you could see why Johnny Rotten might take issue with some of this.

As you put the box set together, was there one song that made you wish you'd done something different?

No, not really. I think I can listen to almost anything we've ever done and think I'd do it differently. But I'd have said the same thing at the time. I very rarely played the same thing identically. I like to think that that's one of the great things about being in this band, that you're not required to slavishly learn every part. But you can reinterpret every song slightly differently every time if you want to. And I think I'm quite forgiving in that respect in terms of listening to things and thinking, actually that's about right. Yes. I would do it differently almost certainly but there's nothing that I really regret. I'd certainly change my shirts and take the mustache off. But musically I'd leave it alone.

When you look back at those old photos, what do you think of those fashions?

I cringe. But that's what we did. Why did I keep wearing this cowboy hat? Someone described my mustache as "adventurous."

The band was far out even then.

Then there was the taste for everyone trying to look Wild West. And everyone had a buckskin jacket with fringes and the more senior you were in the rock 'n' roll hierarchy, the longer the fringes.

And the more beads.

Yeah, the more beads, and the more authentic as well. More or less, if someone looked like a full-blown Indian chief, it was probably Eric Clapton.

Pink Floyd Albums Ranked Worst to Best

More From Ultimate Classic Rock