How Jethro Tull Tried to ‘Out-Prog’ Everybody With ‘Thick as a Brick’

Ian Anderson had a point to make when he turned his thoughts to Jethro Tull’s fifth album. He wanted the work to act as a response to reviews of 1971’s Aqualung, which had been generally positive but was called a concept album.

“Concept album? No,” Anderson tells UCR. “It was just a bunch of songs, and two or three of them happened to have a link. When I came to do the running order and work on the cover text, as you do when you wrap a Christmas present, you choose nice paper and put a nice bow on it. That process in presenting the album gave it some cohesion. But it was whimsical individual oddities, written in hotel rooms, very often in the U.S.”

Anderson decided to prove his point by giving the world what it thought it already had – a genuine Jethro Tull concept album. The result was Thick as a Brick, a milestone in the progressive genre, which arrived on March 10, 1972.

The problem was that a lot of people weren't likely to get the joke. “It was a spoof of what was happening in the world, with particularly British bands like Yes, ELP and Genesis and so on,” Anderson says. Describing his approach as “competitive,” he adds, “I was going to out-prog them, really."

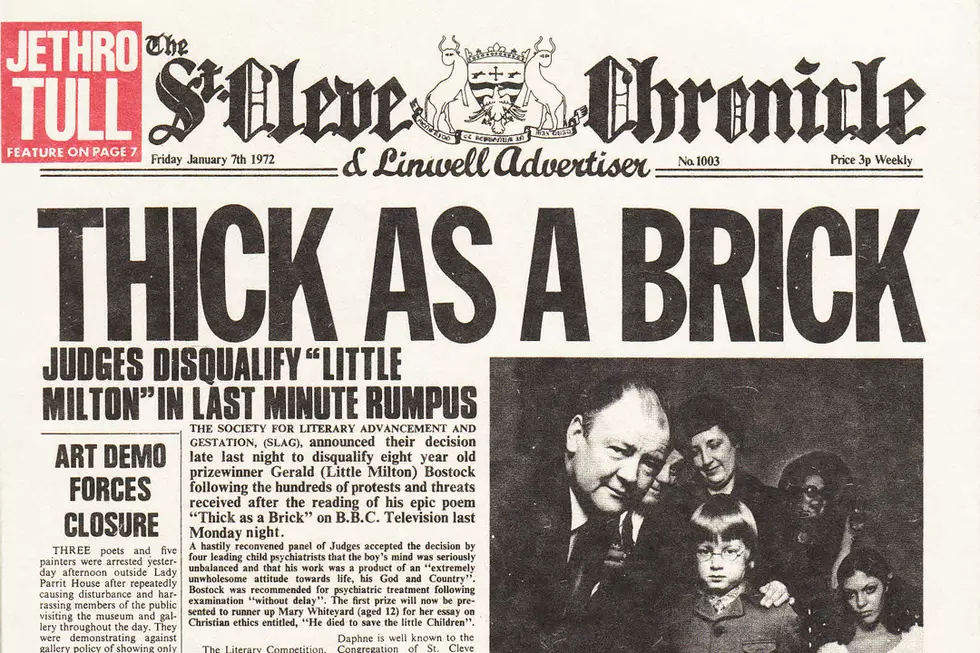

So he was aware he was taking a risk; but instead of shying away, Anderson decided to charge forward. Thick as a Brick featured just one track, split into “Part I” and “Part 2” on the vinyl release, and cut into eight separate titles for the 40th-anniversary edition of the album released in 2012. But that wasn’t far enough. Anderson pretended that the lyrics on the LP had all been written by an 8-year-old boy named Gerald Bostock, who’d become notorious after using a swear word on TV, leading to a poetry award being revoked.

Anderson admits that Bostock’s writing had an element of autobiography about it, in parodying the Boys’ Own-type of publications that portrayed Germans as “Jerries” and fell alarmingly short in providing heroes that weren’t part of the British establishment. “I was subjected as a schoolboy to the nationalistic and unpleasant boys’ magazines, which were not the best way of grooming young minds for the ‘60s and ‘70s,” he notes. “There was a radical change in society, most notable in the U.S. We weren’t prepared for that in schoolboy literature.

“It was that stereotyping that I was lampooning, pretending the album had been written by someone writing adult themes through the distorted mind of a schoolboy," he continues. "It was relatively easy to do. It was a tall order to have it accepted.”

Listen to Jethro Tull Perform 'Thick as a Brick (Part 2)'

His approach had been inspired by a British brand of humor, known mainly in the rest of the world through Monty Python, but remembered as much in the U.K. for the genius of Spike Milligan and the Goons, Round the Horn and many others.

“That humor works, but it’s not just about rib-tickling, wisecracking humor. It’s got to have some substance. It’s got to be making a point,” Anderson says. “Monty Python, at its best, made those points. Sometimes it degenerated and it wasn’t always good, which I’m sure the Pythons themselves would be second to recognize. Sometimes, there were a lot of duds in there.”

To hammer his point home, Anderson created a 12-page provincial newspaper named the St. Cleve Chronicle, which served as the album cover. “It was very carefully studied,” Anderson says. “I amassed a pile of papers and drew inspiration from the really silly stories that people would write about because there wasn’t anything else to write about. That was part of the fun, and definitely made it a concept album.”

That was unfortunate for John Lennon. “He had his album Some Time in New York City in the works. He’d used the The New York Times as the cover. Thick as a Brick came out a few weeks before his – he had a single page, whereas the St. Cleve Chronicle was an altogether more ambitious affair, which luckily made it to the record store before his.”

A one-track record; a fictional lyricist; a spoof newspaper and a very British approach to art. How could it possibly succeed – especially when Jethro Tull’s live set included elements of live comedy cut into the performance? “I had a rule of thumb when we went out and did concerts,” Anderson recalls. “My assumption was that 50 percent of them got it, 50 percent of them didn’t. But 100 percent of them didn’t ask for their money back.

“I think it worked as a musical package," he adds. "Whether people got what was going on was a moot point when you got to countries where English wasn’t even a second language. It wasn’t the international language it is today. People didn’t understand what was going on, but that didn’t stop us from doing well.”

Listen to Jethro Tull Perform 'Thick as a Brick' at Madison Square Garden

Two territories stand out for him. “The Japanese just stared at us blankly, despite our manager Terry Ellis going out on stage with huge signs written in Japanese, explaining the quirky oddities – and apparently naked, although he had underpants on that couldn’t be seen behind the placards," Anderson says. “It was a surprise that it got across in Scotland. My Edinburgh tones had long gone, and as a Scot going back to play something that seemed worryingly English, I felt a little self-conscious. It was a welcome relief that it didn’t antagonize the Scots.”

He was also surprised how well the U.S. accepted the work. “It was a blessed bit of luck that it did okay," Anderson said. "It spent a number of weeks at No. 1 in the Billboard chart, which came as a surprise to everybody – including Mr. Bill Board.”

Nearly half a century on, Thick as a Brick has inspired two follow-up solo efforts: 2010's Thick as a Brick 2: Whatever Happened to Gerald Bostock? (which came complete with an online edition of the St. Cleve Chronicle) and 2014’s Homo Erraticus (which credits Bostock as co-writer).

The original LP remains one of the Tull albums that, for Anderson, “would rise to the surface like the scum on a cold cup of tea." “Stand Up was the first album that wasn’t just pastiche 12-bar blues, so it’s always going to be close to my heart," he says. "Aqualung was a singer-songwriter album, and it marked a difference for me because I was in the studio with an acoustic guitar, performing songs on which the other band members would join in.

“Thick as a Brick was a landmark, then we jump ahead to Songs From the Wood, being more of a folk-rock album; then Crest of a Knave, which did really well in America but not so well elsewhere. You can toss Heavy Horses into that, and I’d guess most people would agree with four or five of my choices.”

Top 50 Progressive Rock Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock