35 Years Ago: ‘Crossroads’ Offers a Twisted Take on the Blues

Robert Johnson went down to the crossroads and, according to legend, sold his soul to the devil for world-changing talent. Ralph Macchio went down to the crossroads and, well, shredded the blues into a speed metal and neoclassical orgy with guitarist Steve Vai in 1986’s Crossroads.

It’s a long, long way from Johnson's raw, rootsy, seminal blues to the pompous, ridiculous, glorious bombast of ’80s hair metal, but director Walter Hill took audiences on that fun and oh-so bumpy trip on March 14, 1986.

The movie stars Macchio as 17-year-old Eugene Martone, a blues fanatic and classical guitar prodigy studying at Juilliard, the prestigious arts conservatory. Eugene’s talent is plain — in class he adds a tasteful blues coda to Mozart’s “Turkish March.” But his classical curriculum leaves him cold. He remains obsessed with the idea that Johnson wrote a lost song that was left off the 1936 recording sessions that produced “Come On in My Kitchen," "Kind Hearted Woman Blues" and "Cross Road Blues.” Eugene’s love of Delta blues and his research on Johnson leads him to harmonica ace Willie Brown, a friend Johnson calls out to in “Cross Road Blues.”

Played by Joe Seneca, Willie has been locked up in a minimum security hospital (maybe he killed somebody, maybe he didn’t). Eugene breaks Willie out of the facility and agrees to get him to Mississippi in exchange for the old bluesman teaching him Johnson’s lost song. The two head South and engage in a not-so-subtle twist on The Karate Kid — here the blues stands in for karate, and Willie turns out to be just as inscrutable as Mr. Miyagi and twice as irascible.

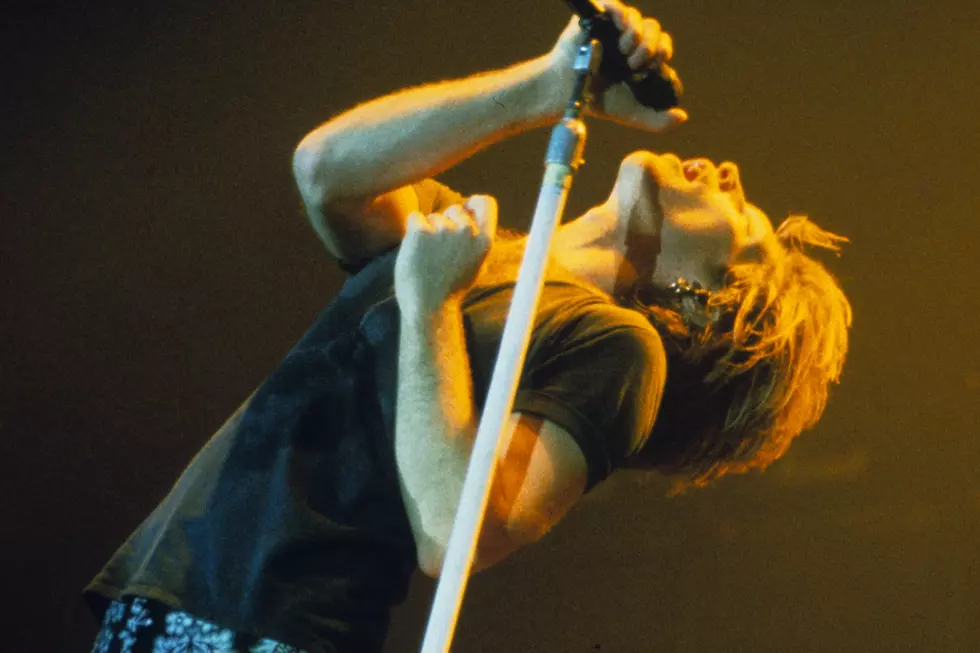

Along the way, the pair “hobo” through the South: hitching rides and walking rural roads, teaming up and quarreling with teenage runaway Frances (Jami Gertz), wowing an audience at a “jook joint” and arguing relentlessly. It all leads to the aforementioned showdown with Vai’s Jack Butler, a guitarist who has sold his soul for skills that make him good enough to stand in for Eddie Van Halen in David Lee Roth’s band.

The whole yarn is fun, dumb, blunt and artful: Hill knows how to shoot a movie, as evidenced by some tense and stylish flashback shots of Johnson done in a blend of black-and-white and sepia. It’s also chock-full of dissonance.

Screenwriter John Fusco, who once worked as a gigging blues musician, wrote the script for his Master's Thesis at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. And as a screenplay, Crossroads has some brilliant turns. One of Willie’s long-running gags is mocking Eugene as a mama’s boy. Can’t play the blues? Go cry to your mama. Can’t pay for bus fare? Go cry to your mama. Afraid to steal a Cadillac by holding a pimp at gunpoint while trying to save your love interest from a live of sex slavery? Go cry to your mama.

(Another great gag comes with Willie repeatedly mocking Eugene for being a “bluesman” from Long Island – but Ry Cooder, who helmed the soundtrack, comes from Santa Monica. If there’s a less bluesy place than Long Island, it’s probably Santa Monica.)

Nicely, Fusco doesn’t shy away from confronting the obvious: Eugene loves the blues but also wants his connection with Willie to bring him fame and fortune. “You're just one more white boy rippin' off our music,” Willie says, referencing, well, arguably everyone from the Rolling Stones to Led Zeppelin and even Cooder. The line comes at a time when many of the Black originators of the music had died but white players doing various versions of their heroes' art were never bigger (see Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan, ZZ Top). Hill, a director who made racial tension a dominant, uncomfortable theme in 48 Hrs., seems in familiar territory here.

Hill’s images, Fusco’s words and Seneca’s Willie make for humor and drama that can rise above the cliches the film trades in. Back in 1986, New York Times critic Walter Goodman summed up what works, writing, “Joe Seneca turns in such a solid performance as an old blues hand in Crossroads that when he is on screen, the movie seems to settle in around him and you can almost overlook the trite goings-on. Almost.”

Instead of following the complex and dark storylines — of which there are many for an ’80s film starring Ralph Macchio and Jami Gertz — down the road, the filmmakers let this darkness disappear. The film brings up questions about race and art, generational differences and art, commercialism and art, but instead of answers it offers a bizarre guitar duel and neatly-tied-up ending full of hope.

The film pushes toward a vision of authenticity. Willie repeatedly ribs Eugene for his soulless renderings of old classics. For 90 minutes, the filmmaker, writer and cast insist that blues must be born in the Delta, developed through pain and treated with the utmost reverence. After all, it’s a music worth selling your soul for. Then we get a flashy, gaudy and downright jarring dream sequence that undercuts the film.

When Eugene and the devil-touched Butler engage in a head-cutting session, or guitar duel, Robert Johnson’s genre is nowhere to be found. Hell, Robert Cray’s genre is nowhere to be found. Instead, the guitarists climax with an electrified, fingers-on-fast-forward mashup of Mozart, Paganini and Yngwie Malmsteen. The nod to Paganini, a 19th-century violin virtuoso who was rumored to be in league with the devil, connects with the narrative, but musically it misses the mark. Eugene wins the duel by abandoning the blues, not celebrating the style.

Despite the happy ending full of lighting-quick hammer-ons, tremolo dive bombs and whammy bar madness, the film knocks at the door of cult classic status. Upon its initial release, it bombed: Nearly $6 million wasn’t enough to even put it in the Top 100 grossing films of 1986. (Notably, bonafide cult classics Clue and Highlander both made about the same at the box office.) But a second life on VHS and cable TV, Cooder’s brilliant score full of slide guitar magic, Vai’s over-the-top histrionics (out of place in the film yet so deeply enjoyable to watch) and the enduring charm of Macchio have kept Crossroads alive.

The film's legacy is a strange one. Undoubtedly, the story and score introduced a generation of teens to Robert Johnson, Willie Brown and the Delta blues. It also anticipated the era of jacked-to-the-max blues-metal and glossy pop-blues. Maybe it pushed Columbia Records to release the 1990 Johnson anthology The Complete Recordings. But it definitely primed the market for hits such as Clapton’s “Pretending,” the Jeff Healey Band’s “Angel Eyes” and the Fabulous Thunderbirds’ "Tuff Enuff.”

10 Essential Movies That Turn 50 in 2021

1971 Movies

More From Ultimate Classic Rock