Pink Floyd’s ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’: A Track-by-Track Guide

Over the course of decades, Pink Floyd’s 1973 album The Dark Side of the Moon has become legendary for a lot of reasons, including the 741 weeks it spent on the album chart, the iconic cover art and the urban-legend connection to The Wizard of Oz. But this track-by-track approach to the LP centers on the music – the sounds, creation and concept behind one of the most successful, popular and celebrated albums in rock history.

“Speak to Me”

The line on Dark Side isn’t just that it’s a masterpiece, but that it’s a masterpiece because the album displays Pink Floyd at the apex of the members’ collaboration. After former frontman Syd Barrett left the psychedelic rockers rudderless, they gradually found a collective focus by 1972, with bassist Roger Waters handling the concepts (and lyrics), guitarist David Gilmour and Rick Wright contributing musical ideas and vocals and drummer Nick Mason maintaining a steady beat while messing with brain-tickling sound effects.

Each of Floyd’s four members received writing credits on Dark Side, although Mason was listed as the sole composer of album opener “Speak to Me.” It was a decision that proved controversial in the later, more acrimonious days of the band (more on this in a bit).

Devoid of lyrics, the one-plus-minute track isn’t much of a song. Conceived in the later stages of the album’s recording sessions at London’s Abbey Road Studios, “Speak to Me” was created as a starting point for this grand, contemplative LP.

“It’s kind of a classical overture, a standard device used for hundreds of years,” Waters told Uncut in 2003, “put some elements of the work together at the beginning, as a taster.”

“Speak to Me” might have been classical in concept, but it was more experimental in execution, with layers of fragmented sonic references to Dark Side’s forthcoming songs. You can hear ticking clocks (“Time”), a cash register (“Money”), crazy laughter (“Brain Damage”) and a woman’s scream (“The Great Gig in the Sky”), all interwoven with the sound of a pulsing heartbeat – created by futzing with the recording of a kick drum. The same pulse is heard at the album’s end, suggesting a continuous cycle.

When Pink Floyd debuted Dark Side’s suite of songs at live concerts (more than a year before the album’s release), the heartbeat sound stood alone as a long introduction that would transition from a venue filled with loud crowd talk to the band’s first proper tune, “Breathe.” For the recorded version, the so-called overture became shorter, but denser – not just featuring elements of other songs, but also snippets of spoken word.

Waters had the idea of recording interviews with people who worked with the band or at Abbey Road Studios, and seeing if the answers might dovetail with some of the weighty lyrical themes of Dark Side. The questions would begin easy (“What’s your favorite color?”) and progress to more difficult subject matter (such as violence or mental instability). The voices on “Speak to Me” belong to the band’s road manager Chris Adamson admitting, “I’ve been mad for fucking years … ,” and Abbey Road doorman Gerry O’Driscoll saying, “I’ve always been mad … ”

In fact, the track’s title came as a result of these interviews. Every time he tested the sound levels to record each interview, audio engineer Alan Parsons would say, “Speak to me” into the talk-back microphone. The phrase stuck. Although Parsons named the piece, Floyd’s drummer was credited for the sonic wizardry on the Dark Side sleeve.

“It was an assembly that I did with existing music,” Mason said, years later. “You could say there’s no original material there, or you could say it’s an entirely original assembly.”

Yet Waters, Gilmour and Wright disagreed with Mason’s memory, instead suggesting that the writing credit was a gift between bandmates – a token of publishing generosity from Pink Floyd’s bassist to the band’s drummer. After Waters split with the band in the ’80s, he didn’t only stop speaking to his former mates, he didn’t want Mason to get any creative recognition for “Speak to Me.”

“I went through many years when I really regretted having given away half the writing credits, particularly ‘Speak to Me’,” Waters said. “I gave it to [Mason]. Nobody else had anything to do with it at all.”

So much for the notion of Dark Side marking the height of Pink Floyd’s collaboration.

“Breathe”

Because the whooshing backwards chord segues from “Speak to Me” right into “Breathe,” the two compositions were most often combined into one track on digital era re-releases. But these are separate pieces, treated as such on the original vinyl release (on which “Breathe” was listed as “Breathe in the Air”). While “Speak” began the album, “Breathe” set the tone for Dark Side.

The first true song on the LP had its roots in a tune, also titled “Breathe,” that Waters had written for a documentary called The Body. Although the two songs don’t have much in common, their lyricist did reuse the title and the opening line for Dark Side. It was a suitable beginning for an album about the universal elements (and impediments) of existence. The first line appears to mark the first breath of life: “Breathe, breathe in the air ... ”

“I think we all thought – and Roger definitely thought – that a lot of the lyrics we had been using were a little too indirect,” Gilmour told Rolling Stone. “There was definitely a feeling that the words were going to be very clear and specific. That was a leap forward. Things would mean what they meant. That was a distinct step away from what we had done before.”

Waters would later sort of cringe at the naked simplicity of some of his Dark Side lyrics, particularly “Breathe,” which follows its first line with “Don’t be afraid to care.” But if the naivete of those words rankled the musician in hindsight, their universality may have helped so many listeners connect deeply with this music. In a matter of a few lines, “Breathe” describes birth, offers parental advice (with a pointed caveat) then helplessly sinks into the infinite loop of the rat race – or is it the rabbit race?

“The lyrics … are an exhortation directed mainly at myself, but also at anybody else who cares to listen,” Waters told Mojo. “It’s about trying to be true to one’s path.”

Waters wrote the words, but Gilmour’s voice contained the delicate power to deliver them – double-tracking his vocal takes to strengthen his breathy cries. His guitar work might be “Breathe”’s defining characteristic – a combination of Stratocaster and lap steel that plants itself in blues structure while zooming to the outer reaches of the universe. The spacey approach was a refined version of what Floyd had done with “Echoes” on 1971’s Meddle.

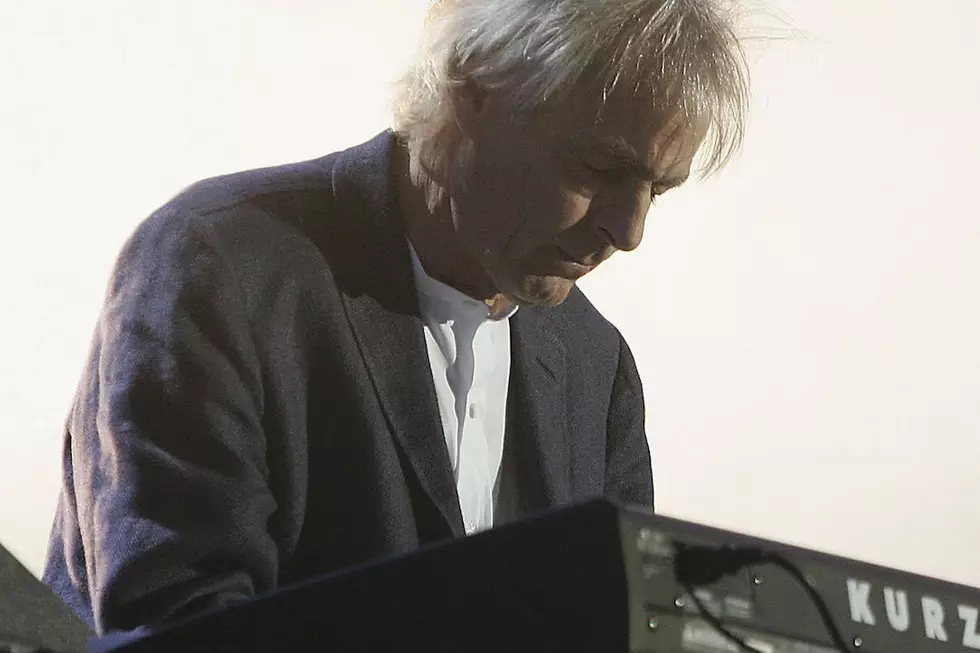

Wright, who shared musical credit with Waters and Gilmour on the song, added textures of keyboard, namely twinkles of Fender Rhodes electric piano and erupting swells of Hammond organ. He also brought in a hint of jazz, via his choice of a minor chord on the way from G to E, right before the verse begins.

“I came from jazz basically … that’s my favorite, that’s my inspiration,” Wright said on the Classic Albums documentary about The Dark Side of the Moon. “The interesting thing about this song … that is totally down to a chord I had heard on, actually, Miles Davis’ album Kind of Blue. … That chord, I just loved.”

“Breathe” would also contribute to Dark Side being looked at as an album-length work. Just as there were sonic and lyrical references to other songs in the LP’s first and last tracks, “Breathe” made a second appearance as a reprise following “Time,” with a slightly different musical approach, a weary word about work and a sneer in the direction of organized religion.

The repeating musical theme “was a bit avant-garde,” according to Mason. “And it was a bloody good device not to have to write anything else.”

“On the Run”

Before “On the Run” existed as one of Dark Side’s most experimental tracks (as such, singled out for praise in a 1973 Rolling Stone review), it existed as a less exceptional guitar-driven jam. When Pink Floyd performed the Dark Side song cycle before they recorded it, the band played something called “The Travel Sequence,” after “Breathe” and before “Time.” It was a kind of interlude to connect two of the major songs.

As Waters was coming up with the lyrical ideas for what would become Pink Floyd’s most famous album, he thought of a list of the things that he thought prevented humanity from progressing. Some of these became the focus (and even the titles) of songs: money, time, morality, violence, etc. One of the more personal themes on Waters’ list was travel, because as a constantly gigging band, the members of Pink Floyd were often on the road, in the air or “On the Run,” so to speak.

“It’s about fear of flying, which we all developed at some time,” Waters said in 2003. Wright had a slightly different take: “I was exhausted by the treadmill, the grind of traveling. For me, it expressed that rather than the fear of crashing in an aircraft.”

Perhaps because it was so personal, Waters didn’t compose lyrics about this particular fear, and the song remained an instrumental. When the Floyd members entered Abbey Road Studios to begin recording Dark Side, “The Travel Sequence” turned into something more bizarre, futuristic, frightening and alien. As that stage jam became “On the Run,” the track found its backbone in a synthesizer, the EMS Synthi AKS.

“I put an eight-note sequence into the Synthi and sped it up,” Gilmour recalled. “Roger thought it wasn’t quite right. He put in another, quite like mine. I hate to say, it was marginally better.”

If the constantly oscillating, ever-repeating sci-fi sound of the Synthi AKS didn’t fully represent what Wright called “the grind of traveling,” extra effects hammered the idea home. Along with heavily manipulated guitar and organ, folded into the track were an airport announcement (“Have your baggage and passport ready …“), other synthesized noises (which sounded like a vehicle swooping past) and a little more everyman philosophy (“Live for today, gone tomorrow. That’s me,” as said by Floyd road manager Roger “The Hat” Manifold).

Engineer Parsons has claimed it was his idea to add the sound of a man’s running footsteps and gasps of heavy breathing. “Often I’d carry on experimenting after they had gone," he recalled. "The footsteps were done by Peter James, the assistant engineer, running around Studio 2, breathing heavily and panting. They loved it when they heard it the next day.”

Going out with a, quite literal, bang, “On the Run” ends with the sound of a plane crash – leaving little interpretation to how a traveling band felt about their concert schedule. The track’s finale became even more dramatic when performed on the tour to promote Dark Side, as Pink Floyd arranged for a huge model airplane to “fly” across arenas and “crash” in a rigged explosion. The stagecraft, although intense, seemed to lighten the band’s dark thoughts on the subject of air travel.

“We’ve had all sorts of things over the years, so I don’t think it put any of us off,” Gilmour remembered about the special effect. “It was jolly entertaining.”

“Time”

Everyone in Pink Floyd gets their shot at the spotlight in “Time.” Mason does his drum solo on the rototoms in the big build-up, Wright came up with some of the epic chord changes and offers his gentle lead vocal (for the last time on record until the ’90s) on the bridges, Gilmour’s snarling singing on the verses is only outdone by his blistering guitar solo and Waters (as throughout Dark Side) came up with the idea and wrote all the lyrics.

“Time” is the only song on the album on which all four members receive a writing credit – making it the zenith of collaboration on what the Floyd guys have always claimed was their most cohesive LP as co-workers. And it’s only appropriate that each gets his moment on a track that focuses on living in the moment.

Waters has said the words for “Time” came from a eureka moment he experienced as he approached the age of 30 and Floyd were putting together Dark Side. He had spent his adolescence and young adulthood waiting for life to begin, only to discover that he was already living it. The notion is reflected in the lyric, “And then one day you find 10 years have got behind you / No one told you when to run, you missed the starting gun.”

“I suddenly thought at 29, ‘Hang on, it’s happening’,” Waters told Mojo. “It has been right from the beginning, and there isn't suddenly a line when the training stops and life starts. … To be here now, this is it. Make the most of it.”

When the band began to record “Time” in the studio and audio engineer Parsons learned of the song’s title, he offered his own contribution. Not long before Floyd started sessions for Dark Side, Parsons had gone to a watchmaker’s shop to record a range of clocks going off. He planned to use the sounds on a release that would demonstrate the capabilities of quadraphonic sound. Instead, the tolling clocks became a memorable part of “Time,” presaging the song’s slow climb.

“We were doing the song ‘Time,’ and he said, ‘Listen, I just did all these things, I did all these clocks’,” Gilmour remembered in 1984, “and so we wheeled out his tape and listened to it and said, ‘Great! Stick it on!’ And that, actually, is Alan Parsons’s idea.”

The engineer wasn’t the only outsider to make a key contribution to “Time.” Dark Side’s most dynamic track featured vocal backing by four female singers – Doris Troy, Leslie Duncan, Liza Strike and Barry St. John. Recordings of the women’s voices were fed through a pioneering pitch-shifting device invented at Abbey Road Studios. The Frequency Translator wasn’t employed as suggested; instead Floyd members and Parsons manipulated the vocals to bring a greater “swishing” sweep to the soulful “oohs” and “aahs.”

Everything about “Time” was big: its cacophony of clocks, its sonic range from hushed tick-tocking to full-throated rock exuberance, its notions about the hourglass of life, its seven-minute length. It also might be Dark Side’s hardest-rocking moment with Waters’ bass digging deep into the song’s funky gait and Gilmour burning through everything with his blazing arrow of a guitar solo coated in space echo.

“Some punch, some rock guitar,” is how the guitarist described the approach to Rolling Stone in 2011. “You know, once you’ve had that guitar up so loud on the stage, where you can lean back and volume will stop you from falling backward, that’s a hard drug to kick.”

In “Time”’s closing moments, Pink Floyd break the fourth wall. Wright’s lamenting vocals deliver Waters’s lyrics: “The time is gone, the song is over / Thought I’d something more to say … ” The album’s lyricist isn’t just using the song to write about the human perception of time, he’s using the creative process as a metaphor for life and how the clock will inevitably run out on everyone.

“Maybe we all suffer from the feeling of lost opportunities, or you could have done better, or done more,” Waters told Uncut. “Maybe it’s comforting to hear that feeling expressed in a piece of work that’s been as successful as this one. People often think, ‘If only … I could write the hit song, or have the success, everything would be okay.’ It’s very nice, but it doesn’t solve any of the problems you might feel about yourself.”

Then, via a dissonant chord, “Time” transitions to a one-verse reprise of “Breathe” (same melody, but new words). The reprise – all but exhaled by Gilmour – gets a lot done in a mere eight lines. It reiterates the “stop and smell the roses” idea of “Breathe” proper, connects to the chimes of “Time” (“the tolling of the iron bell”) and introduces some old-time religion (“hear the softly spoken magic spells”). All of it just in time for Dark Side to move on to mortality.

“The Great Gig in the Sky”

Because of her singing on “The Great Gig in the Sky,” Clare Torry’s name is inextricably linked to Pink Floyd. And she wasn’t even a fan of the band.

The idea to bring in a singer to “wail” on the track happened late in the recording sessions for Dark Side (mid-January 1973, only about a month-and-a-half before the album’s release). When Pink Floyd had performed the Dark Side material live in 1972, before recording it, this spot in the song cycle had been taken by something termed “The Mortality Sequence.” The theme was religion and death, exemplified by Wright playing an organ with taped snippets of recorded prayers and Christian commentary playing over the live performance.

When the band got into Abbey Road Studios, Wright refined the piece and crafted something more delicate, playing piano as the tune’s lead instrument. Gilmour contributed pedal steel, Waters played bass and Mason handled the drums. Everyone seemed to love the instrumental (Waters later praised it as “really beautiful” and one of “the best things that Rick did”), yet some of the members felt it needed something more.

The idea of keeping the prayers and Bible verses from the live edition was quickly dispatched and the band moved on to trying to use recordings of astronauts communicating in space (which didn’t gel) as well as subjects from Waters’ interview idea (two of whom ended up on the completed track). But the quotes from Abbey Road doorman Gerry O’Driscoll – “And I am not frightened of dying … " – and Patricia “Puddie” Watts, wife of road manager Peter Watts – “I never said I was frightened of dying” – weren’t quite enough to capture the emotion of a song about death.

No one remembers whose idea it was (rare in a band in which so many seem eager to take credit), but eventually the guys in Floyd decided that a female singer might do the trick. Engineer Parsons suggested a young singer-songwriter named Clare Torry, because he had been impressed by the power of her voice on a cover of the Doors’ “Light My Fire.” The 25-year-old singer initially was reluctant to take part. Torry wasn’t into progressive rock and had tickets to a Chuck Berry concert on the Saturday night proposed for the session, but she eventually agreed when the date was set for a Sunday.

“I think one has to give Clare credit -- she was just told to go in and ‘do your thing,’ so effectively she wrote what she did,” Parsons said in 1998. “She wailed over a nice chord sequence. There was no melodic guidance at all apart from ‘a bit more waily here’ or ‘more somber there.’ The vocal was done in one session – three hours – no time at all, then a couple of tracks were compiled for the final version.”

The members of Floyd had been at a loss at how to direct someone to sing a completely wordless part for a song that was serious yet carried the playful title of “The Great Gig in the Sky.” Although they came away impressed with Torry’s hair-raising, even terrifying, vocal takes, the guys’ stone-faced manner belied their approval.

“The only thing I could think of was to make myself sound like an instrument, a guitar or whatever, and not to think like a vocalist,” Torry recalled. “I did three or four takes very quickly, it was left totally up to me, and they said, 'Thank you very much.' In fact, other than Dave Gilmour, I had the impression they were infinitely bored with the whole thing, and when I left I remember thinking to myself, ‘That will never see the light of day’.”

Torry didn’t know she had become part of Pink Floyd’s hit album – and, eventually, one of the most beloved LPs of all time – until she spotted Dark Side in a record shop one day and saw that she was credited on the sleeve. Although Wright was listed as the song’s sole writer, that changed after a retired Torry sued the band and EMI in 2004, resulting in a settlement that gave the singer-songwriting credit on subsequent reissues of the album.

“I get so excited when I hear Clare singing,” Wright said in 2003. “For me, it’s not necessarily death. I hear terror and fear and huge emotion, in the middle bit especially, and the way the voice blends with the band.”

“Money”

Pink Floyd hadn’t had a hit single since 1967. That was back when they were a psychedelic outfit led by Syd Barrett. By the mid-’70s, the singles chart just wasn’t the kinetic playground for progressive rock bands. Groups of Floyd’s ilk gravitated toward longer artistic statements: albums with big concepts, extended tracks and lots of room for listeners’ minds to wander. This wasn’t Top 40 stuff.

Yet, suddenly in 1973, it was. A couple months after the release of Dark Side, Pink Floyd put out an edited-down version of “Money” as a single in the U.S. and it soared to No. 13 on the Billboard chart, helping to take the British band from an underground act to a popular sensation in North America. Sure the song was catchy – with its distinctive, rubber-band bass line and blistering solo breaks – yet it was still a surprise that a song written in the decidedly un-pop time signature of 7/4, with a sound effects loop, an unsung chorus and a subversive attitude toward capitalism would become a Top 20 single on American radio.

As with all of the Dark Side material, Waters was responsible for those sarcastic lyrics, which were written to a strange rhythm as the bassist was considering the elements that could prove dangerous to a thriving society. As a rock musician who was working to be rich and famous, but also had notions of socialism, Waters decided to go the “funny and clever” route.

In addition to the off-kilter time signature, Waters came up with the idea of creating a sound effects loop that would insert into the track the literal sounds of money (coins, bags of cash, registers, etc.). Drummer Mason helped Waters begin collecting this rhythmic loop in the song’s home demo stage.

“I had drilled holes in old pennies and then threaded them on to strings,” Mason explained in his autobiography Inside Out. “They gave one sound on the loop of seven. Roger had recorded coins swirling around in the mixing bowl [his then-wife] Judy used for her pottery. Each sound was measured out on the tape with a ruler before being cut to the same length and then carefully spliced together.”

The final version of the seven jangling, ripping, clinking and ringing sounds was used by Dark Side engineer Parsons as a click-track, to which the members of Pink Floyd played when recording “Money” at Abbey Road Studios. Because Parsons slowly faded out the effects in the band’s headphones, the song begins to move faster after the guys were untethered from their weird metronome.

Wright and Gilmour initially weren’t thrilled with the Waters composition. The keyboardist later claimed it was the one song that didn’t fit with the rest of Dark Side and also disagreed with the political nature of the lyrics at the time (after all, he was the one who agreed for “The Great Gig in the Sky” to be used in a commercial for headache medicine). Gilmour was, at first, unsure about singing and playing to the awkward 7/4 time. Although he came around to the idea, he made sure that “Money” switched to a more standard 4/4 time for his series of guitar solos.

He didn’t merely dash off the solos, which include some of the heaviest rock on the entire album and, essentially, take the place of the choruses in a typical song structure. Gilmour treated each iteration differently, changing the guitar he played (a Fender Stratocaster on the first two solos, a customized Lewis guitar capable of achieving higher notes on the last one). He also planned the contrast of a “wet” sound – reverb and delay effects on the first solo – with a “dry” approach in the middle, then returning to a fuller aesthetic for the final, more chaotic turn. Much of his driving approach on guitar was a tribute to the Memphis sound.

“I was a big Booker T. fan,” Gilmour later revealed, in reference to Stax Records house band, Booker T. and the M.G.’s. “I had the Green Onions album when I was a teenager. … It was something I thought we could incorporate into our sound without anyone spotting where the influence had come from. And to me, it worked. Nice white English architecture students getting funky is a bit of an odd thought.”

Another R&B element was added with the addition of Dick Parry’s blurting and squealing saxophone. The story goes that Gilmour told his former bandmate to play like the saxophonist in a cartoon ad that ran before movies in Britain.

“I played with him. He was a jazz player. You’d be in two or three different groups at a time sometimes. My group in Cambridge very rarely had a gig on a Sunday night, and Dick had a regular spot in a ballroom on a Sunday night. We got this jazz trio thing going on,” Gilmour said in 2003. “Pink Floyd … really didn’t know how to get hold of a sax player or anything. We wanted to try a sax on ‘Money’ and ‘Us and Them,’ so we got Dick in.”

In addition to Parry’s sax work, Pink Floyd filtered in more of spoken-word snippets, of the same variety that had appeared on other tracks. A run of a variety of voices (including Wings member Henry McCullough) close out the song, not responding to financial questions, but matters of conflict, perhaps as a preview of Dark Side’s next track.

Looking back decades later, the irony was not lost on the band regarding “Money” being, in many ways, responsible for the vast material success of Pink Floyd. It was practically a prophecy, given the lyric that Waters wrote and Gilmour sang “Money, it’s a hit.”

“We were by no means rich at that time. ‘Money’ is the single that helped to really break us in America,” Gilmour said. “It was the track that made us guilty of what it propounds, funnily enough.”

“Us and Them”

The oldest song in Dark Side, “Us and Them” dates from four years before the album’s release, when Pink Floyd had been commissioned by film director Michelangelo Antonioni to create soundtrack music for Zabriskie Point. Wright, the band’s keyboardist, had written this subdued, melancholy piece to work as a contrast to a scene that depicted a campus riot. As such, it had the working title of “The Violence Sequence.”

“It has quite a simple chord sequence, except for the rather strange third chord, influenced by jazz,” Wright told Uncut, referencing the D minor chord with a major seventh. “It was an augmented chord, hardly ever used in pop music then.” It proved unusual for pop music and, as it turned out, a bit too unusual for Antonioni as well. While the Italian director loved Floyd material such as “Careful With That Axe, Eugene,” he wasn’t thrilled with Wright’s slow, piano tune. Waters recalled the filmmaker’s reaction: “It’s beautiful, but is it too sad, you know? It makes me think of church.” Antonioni chose not to use “The Violence Sequence” for his movie.

A few years later, Pink Floyd were starting to assemble material for what would become Dark Side and Wright was still kicking around this chord progression in his brain. The song ended up underscoring a different sort of conflict: warfare, prejudice and inequality as depicted in lyrics written by Waters. The bandmates worked on the song, now called “Us and Them,” together, adding a new musical section and words that paid heed to the forces that prevent human beings from connecting.

“We needed a middle-eight. I came up with the chords for that,” Wright said. “It’s very flowing and sweet if you look at the verse, then there’s the contrast, this big, harder chorus. With the lyrics about the war and the general sitting back – it worked so well.”

Wright and Waters were so pleased with “Us and Them,” which Pink Floyd performed while on tour before making Dark Side, that the deceptively serene song became the first one recorded for the album when the band entered Abbey Road Studios in June 1972. Gilmour sings the lead part, his voice processed with an echo effect to enhance the dichotomy of certain lines (i.e. “Us … us … us … us … us … us … us … and them … them … them … them … them … them … them …”).

Wright’s vocals come in to harmonize in the crescendo of the choruses, as do the voices of Doris Troy, Leslie Duncan, Liza Strike and Barry St. John, who sing backup on other tracks (“Time,” “Brain Damage” and “Eclipse”).

“All our vocals are perfectly balanced – for instance, on ‘Us and Them’,” Gilmour noticed. “I did I don’t know how many harmony vocals, then the girls on top. It’s really great, really uplifting. You can move one element a fraction and the whole thing falls to pieces.”

As with “Money,” it was Pink Floyd’s guitarist who brought in old pal Dick Parry to play saxophone on the track. The jazzman delivers two solos, each breathy and moody, in stark contrast to the honking assignment on his other Dark Side appearance. Just before his second solo on “Us and Them,” listeners hear yet another of the album’s spoken-word snippets, with roadie Roger “The Hat” Manifold holding forth on the theme of violence (“So if you give ’em a quick short, sharp, shock, they won’t do it again”).

Wright and Waters, the song’s co-writers who would so often find themselves at odds in the post-Dark Side era, would eventually look back fondly on “Us and Them.” Even in the years in which they were not talking to one another, they each considered their collaboration a highlight, if not the all-out centerpiece, of Pink Floyd’s most legendary album.

“It’s a great example of the music and the lyrics combining to create emotion,” Wright said in 2003. A few years earlier, Waters had offered, “The whole idea, the political idea of humanism and whether it could or should have any effect on any of us, that’s what the record is about really – conflict, our failure to connect with one another.”

“Any Colour You Like”

When the Dark Side collection of songs existed as merely a concert set – before Pink Floyd went into the studio to record the album – the material included two instrumental jams that both served as connective tissue for the entire cycle. There was one jam in between “Breathe” and “Time” (which was radically altered for the album to become “On the Run”) and there was another between “Us and Them” and “Brain Damage.”

Because Floyd had deep-sixed the first jam, the members were content with keeping the second one for the LP, although it still got the full studio treatment. Segueing from “Us and Them,” the instrumental is led by a heavily addled EMS VCS 3 synthesizer played by Wright, which eventually yields the floor to Gilmour’s guitar playing, including a harmonized solo. Wright also contributes organ and another synth, while Waters plays bass and Mason is on drums.

The funky instrumental has been occasionally referred to as the second reprise of “Breathe” because it has the same rhythm (albeit more up-tempo) and boasts a similar chord sequence to that song (although stepped down from E minor to D minor). So even if “Any Colour You Like” doesn’t have an obvious impact on the overall themes of Dark Side, it does play into a repeated musical element of the LP.

“It’s not a vital part of the narrative,” Gilmour said in 2003, “but there are moments when it’s nice to get off the leash and just play.”

Yet Waters, who is the only Floyd member not credited with writing the song, has claimed that “Any Colour You Like” does contain an underlying message to match some of the other impediments to progress explored in the lyrics and music of Dark Side.

Although it has been suggested that the title is an in-joke, referencing Floyd roadie Chris Adamson’s catchphrase, Waters told author Phil Rose that the phrase originated with his memory of salesmen hawking cheap items out of a van. “If they had sets of china, and they were all the same color, they would say, ‘You can ’ave ’em, 10 bob to you, love. Any color you like, they’re all blue’,” Waters recalled in Which One’s Pink? “And that was just part of that patter. So, metaphorically, ‘Any Colour You Like’ is interesting, in that sense, because it denotes offering a choice where there is none.”

“Brain Damage”

This track gave the entire album its title. When Waters was first working on it, around the time that 1971’s Meddle was being recorded, “The Dark Side of the Moon” was the name given to the song. Before it arrived at its final name, “Brain Damage,” it had the working title “The Lunatic Song” – named as such for the lyrics’ frequent use of the term.

The song’s first line is “The lunatic is on the grass,” a general reference to “keep off the grass” signs and a specific memory of a beautiful lawn in Waters’ hometown of Cambridge on which he desperately wanted to run around. The songwriter would later remark that the real lunatics are the ones trying to prevent people from lazing on a nice patch of grass.

But the larger inspiration for Waters’ acoustic-based tune was his former bandmate, and Pink Floyd’s first frontman, Syd Barrett. His relationship with, and proximity to, someone with destabilizing mental illness would greatly impact Waters’ work in Pink Floyd, including parts of Wish You Were Here and The Wall. In “Brain Damage,” the lyric “And if the band you’re in starts playing different tunes” is a nod to concerts in which Barrett would be performing a completely different song to the one that the band had agreed to play.

“It was a huge shock to me to see the ravages of schizophrenia at those close quarters,” Waters said in 2003. “There’s no way to deal with it. Certainly there wasn’t with Syd.”

So “Brain Damage” was, in part, Waters’ way of dealing with this. It wasn’t just references to Barrett, grass and lobotomies, but a display of empathy for the folks on the fringes – “defending the notion of being different,” as the songwriter put it on the Classic Albums documentary. The song’s lyrical hook, after all, is “I’ll see you on the dark side of the moon,” as if to say that there isn’t that much different between Barrett and Waters. “It’s also to suggest that there’s a camaraderie involved in the idea of people who are prepared to walk the dark places alone,” Waters said. “You’re not alone! A number of us are prepared to open ourselves up to all those possibilities.”

At the time Pink Floyd were making Dark Side, Waters was still self-conscious about his singing voice, especially in contrast the expressiveness of Gilmour’s vocals. But it was the guitarist who convinced Waters to sing on “Brain Damage,” possibly because of how personal the lyrics were.

Besides, it’s not like the recording did a disservice to the apprehensive singer. Waters stands alone on the quieter verses, but is joined by Gilmour and the backing contingent of Doris Troy, Leslie Duncan, Liza Strike and Barry St. John on the operatic choruses, which blast out of the simple, folky tune.

Gilmour’s sighing space guitar, Wright’s bum-rushing Hammond organ and Mason’s thunderous drums make “Brain Damage” suitable for Dark Side’s widescreen canvas, while clips of road manager Peter Watts laughing like a maniac maintain the conceptual connections.

“It’s very simple, and also it has the mini-Moog,” said Wright, who wasn’t thrilled, originally, with the recording. “It’s got a hotel orchestra kind of sound. I love the chorus, and the girls blended in so beautifully.”

“Brain Damage” also blended in so well with Dark Side’s final track, “Eclipse,” that the pair are usually performed in concert or played on the radio in tandem, causing many fans to consider them one piece – even though they were written as separate songs.

“Eclipse”

Pink Floyd were already in the process of a 1972 road-test of the material that would turn into Dark Side when lyricist and bassist Waters realized the suite of songs was missing something. Sure, the band had big, dramatic think-pieces such as “Time” and “Money” and “Us and Them,” but not a song that tied all of the themes together.

“I suggested it all needed an ending,” Waters told Uncut. “I wrote ‘Eclipse’ and brought it into a gig in Colston Hall in Bristol [the eighth of the tour on which the Dark Side songs were being played], on a piece of lined paper with the lyrics written out.”

But it wasn’t titled “Eclipse” at the time; it was called “End.” That’s because Floyd were considering calling the entire piece Eclipse, scared off of the original Dark Side of the Moon moniker because another British band, Medicine Head, was releasing an LP with that title. That album proved unsuccessful, Pink Floyd reverted to their plan and “Eclipse” became the name of the record’s final track.

Lyrically, the conclusion does what Waters set out to achieve, forging bonds between many of the other songs on Dark Side. In the first line, Waters practically repeats a lyric from “Breathe” (“All that you touch / And all that you see”), while other phrases in this litany of themes bring to mind “Money” (“And all that you buy, beg, borrow or steal”), “Time” (“And all that is now / And all that is gone / And all that’s to come”) and “Us and Them” (“And all that you fight / And everyone you slight”).

If Waters met his goal as a lyricist, it would require the entire band to take this short, repetitive song into (interstellar) overdrive. Shooting straight out of “Brain Damage,” a giant wave of Wright’s Hammond heralds this musical and thematic climax, punctuated by Mason’s drums and surrounded by Gilmour’s twinkling guitars.

“I remember working hard on making it build and adding harmonies that join in as you go through the song,” Gilmour told Rolling Stone about recording the song. “Because there’s nothing to it – there’s no chorus, there’s no middle eight, there’s just a straight list. So, every four lines we’ll do something different.”

A big part of that build was the addition of the same female vocalists – Doris Troy, Leslie Duncan, Liza Strike and Barry St. John – who had appeared elsewhere on Dark Side. It provided consistency, in terms of the album, and emotion, in terms of the song. Where they did a lot of ooh-ing and ahh-ing on other tracks, the women are less restrained on “Eclipse.” Troy, in particular, goes all-out with her wailing, providing a tie to Clare Torry’s turn on “The Great Gig in the Sky” while also underscoring the universality Waters was trying to get across in this conclusion. One of the lyrics she echoes in her soulful howl is “Everyone you meet.” Meanwhile, nearly every line that Waters sings contains the word “all,” “everyone” or “everything.”

The song, and album, culminates in the final lines: “And everything under the sun is in tune / But the sun is eclipsed by the moon.” It isn’t merely a reference to the album’s title or the lyric in “Brain Damage,” but a crystallization of everything Waters intended Dark Side to be about.

“It isn’t very positive, but it’s very true,” he admitted in 2003. “Saying that there’s the potential to express the positive side of everything, but that all the stuff that we have talked about on the rest of the record has the potential to get in the way, and it’s up to us to make a change. We all get to choose to some extent … ”

Then the organ fades into the darkness and listeners hear one last interview snippet, a final thought from Abbey Road Studios doorman Gerry O’Driscoll, “There is no dark side of the moon, really. Matter of fact, it's all dark.” And Dark Side retreats to Mason’s drumbeat pulse, the same steady sound of life heard at the album’s start.

Pink Floyd Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock