How Robert Zimmerman Became Bob Dylan

Robert Allen Zimmerman emerged from the Supreme Court building at 111 Centre St. in downtown Manhattan on Aug. 2, 1962, as Bob Dylan – but it wasn't his first name change, or the last.

He'd been going by Bob Dylan since around the time of his arrival at the University of Minnesota in September 1959. "The first time I was asked my name in the Twin Cities," he writes in the 2004 autobiography, Chronicles: Volume One, "I instinctively and automatically, without thinking, simply said: 'Bob Dylan.' Now, I had to get used to people calling me Bob."

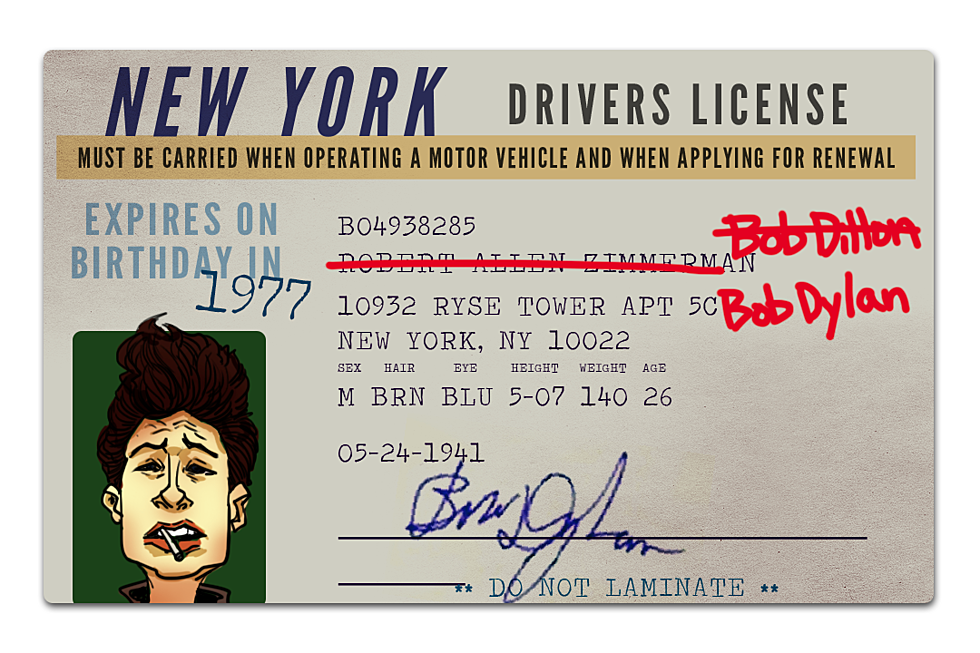

Before that, Robert Zimmerman had been known as Elston Gunn. He also considered different formulations of his birth name, including Robert Allyn, and used variations on his most famous stage name, like Bob Dillon. (He was said to have mentioned the latter stage name as early as his junior year in high school.) The Gunn pseudonym was the first to gain wide notice, however, after Dylan used it during a brief late-'50s tenure in pop singer Bobby Vee's band, when Zimmerman was barely out of high school.

Family members, like close cousin Reenie, were understandably confused by the name change. "One time, she asked me why I was using a different name when I played, especially in neighboring towns. Like, didn't I want people to know who I was?" Dylan recalls in Chronicles. "'Who's Elston Gunn?' she asked. 'That's not you, is it?' 'Ah,' I said, 'you'll see.'"

Even then, Dylan knew there were more masks yet to come. "The Elston Gunn name thing was only temporary," he adds in Chronicles. "What I was going to do as soon as I left home was just called myself Robert Allen. As far as I was concerned, that was who I was – that's what my parents named me. It sounded like the name of a Scottish king, and I liked it. There was little of my identity that wasn't in it."

Of course, Robert Allen didn't stick either. The convoluted journey Zimmerman would take in choosing Bob Dylan as his new name has become its own enduring mystery. The most commonly accepted version has long been that it was a tribute to poet Dylan Thomas. Later, another theory posited that his pseudonym grew out of an early appreciation for the Matt Dillon character in the TV series Gunsmoke.

The ever-enigmatic Dylan – who told Playboy in 1978 that "I just chose the name and it stuck" – was typically of no help. Long after signing the first management contracts that finalized his new identity, he claimed that Dylan was his mother's maiden name (when it was actually Stone), that there was a Dillon Road in his hometown of Hibbing, Minn., that he took it from the name of a town in Oklahoma and that he had an uncle on his mom's side of the family with a similar name.

He even took shots at Thomas along the way. "Dylan Thomas' poetry is for people that aren't really satisfied in their bed – for people who dig masculine romance," Dylan told The New York Times in 1961. "I didn't change my name in honor of Dylan Thomas: That's just a story," he told Jules Siegel during a 1966 interview quoted in Bob Dylan: The Never Ending Star. "I've done more for Dylan Thomas than he's ever done for me."

Listen to Bob Dylan Perform 'Man Gave Names to All the Animals'

A careful reading also reveals that Dylan's songs have little in common with the Welch poet's work. Yet, the Dylan Thomas theory tended to stick – in part because Zimmerman was, in fact, a youthful fan. In Who Is That Man?: In Search of the Real Bob Dylan, childhood friend Larry Kegan remembered Dylan "usually had a poetry book in his hand – sometimes the poems of Dylan Thomas." More particularly, Dylan has confirmed the Thomas connection in separate interviews, and was even said to be considering a centennial concert appearance in Thomas' hometown at one point.

Dylan's most complete explanation likely appeared in Chronicles, when he mentions coming across an article about a jazz performer named David Allyn in Downbeat magazine. Thomas played a role in this version of events too.

"I had suspected that the musician changed the spelling of Allen to Allyn," Dylan said. "I could see why. It looked more exotic, more inscrutable. I was going to do this too. Instead of Robert Allen, it would be Robert Allyn. Then, sometime later, unexpectedly, I'd seen some poems by Dylan Thomas. Dylan and Allyn sounded similar: Robert Dylan, Robert Allyn. I couldn't decide – the letter D came on stronger. But Robert Dylan didn't look or sound as good as Robert Allyn. People had always called me either Robert or Bobby, but Bobby Dylan sounded to skittish to me, and besides there was already a Bobby Darin, a Bobby Vee, a Bobby Dydell, a Bobby Neely and a lot of other Bobbys."

That led him, finally, to Bob Dylan. But his past remained inscrutable as he constructed similarly ever-changing tales involving a bohemian lifestyle far different from his middle-class Jewish upbringing. In fact, he's never stopped trying on new guises.

Dylan played harmonica on a 1964 album by Ramblin' Jack Elliott as Tedham Porterhouse. He anonymously recorded a set of legacy folk songs around the same time as Blind Boy Grunt. Robert Milkwood Thomas, the pianist on Steve Goodman's 1972 album, Somebody Else's Troubles, was actually Dylan.

He appeared as Lucky Wilbury on 1988's Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1, then as Muddy Wilbury on the 1990 follow-up Vol. 3. He's been self-producing albums under the name Jack Frost since the turn of the '90s, as well. He also co-wrote the screenplay for the 2003 movie Masked and Anonymous as Sergei Petrov. That followed a role in 1973's Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid where Dylan's character name seemed like something of an inside joke: He played a stranger called "Alias."

Dylan made no excuses along the way. "You're born, you know, the wrong names, wrong parents – I mean, that happens," he told CBS in 2004. "You call yourself what you want to call yourself. This is the land of the free."

How 100 of Rock's Biggest Bands Got Their Names

More From Ultimate Classic Rock