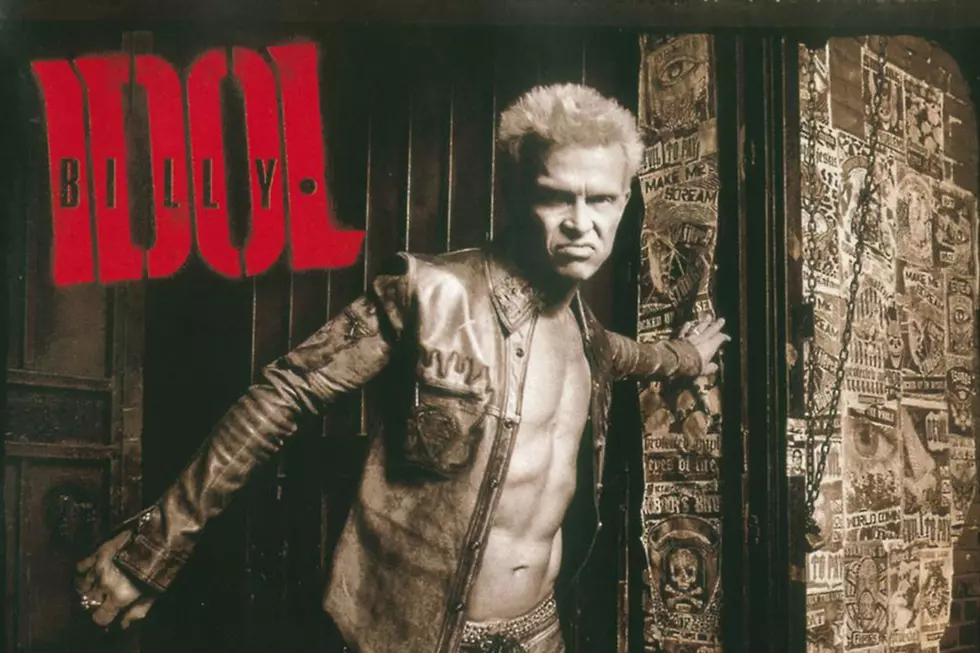

15 Years Ago: Billy Idol Raises ‘Devil’s Playground’ Comeback

After Cyberpunk flopped there was nowhere for Billy Idol to go but up.

“The immediate reaction to [Cyberpunk] humbled me,” Idol wrote in his 2014 autobiography, Dancing with Myself. The one-time high-profile MTV attraction took a six-year sabbatical from the concert stage, resurfacing for a well-received role in the Adam Sandler comedy The Wedding Singer and a 2001 cover of Simple Minds’ “Don’t You (Forget About Me),” but musically Idol was unmoored.

After woodshedding with longtime partner Steve Stevens on an album that never materialized, Idol resumed touring with a band that included a new collaborator, guitarist and drummer Brian Tichy. By 2005, with Stevens on board alongside Tichy, a revitalized Idol was itching for a comeback. His vehicle, Devil’s Playground, would feature collaborative songwriting by Idol and Tichy, as well as tunes Idol penned in tandem with Stevens. It was designed to be a ferociously hard rocking, emo-inspired album that would also connect with the tone of Idol’s '80s classics. At least, that was the plan. As Idol would discover, the devil was in the details.

Upon its release on March 22, 2005, Devil’s Playground drew guardedly positive reviews. Critics like Slug Mag’s Ryan Michael Painter seemed happy to have the sneering Idol of old back, declaring the album “1985 redux” as well as the year’s best guilty pleasure. Allmusic’s Stephen Thomas Erlewine praised the disc’s killer tunes, while declaring himself perplexed by Idol’s appropriation of hard-edged heavy metal. “[It’s] as if his posturing in the '80s was more than an affectation,” Erlewine wrote.

At this point, backhanded compliments from critics were boilerplate for Idol. A perusal of contemporary reviews of classics like his self-titled debut, 1983’s Rebel Yell and 1986’s Whiplash Smile, reveal a pervasive attitude that Idol is an enjoyable poser, a two-dimensional peroxided plastic punk. In reality Idol’s artifice has always been his strength. His best work harnesses '80s' clichés -- overbearing beats, sheets of synths and Stevens’ atmospheric guitar pyrotechnics -– to sophisticated pop that seamlessly meshes soul, ballads and even folk to a rock beat.

In this respect, Devil’s Playground draws on Idol’s best instincts. Under the production of Keith Forsey, who had helmed Idol’s solo debut album, the artist here is energetic, restlessly curious and willing to take risks and fall flat on his face. But Painter’s and Erlewine’s reviews point to the schizophrenia inherent in the disc. It’s far more metal than any of idol’s previous efforts, often emulating emo’s push-pull of hard and soft, metal and pop, with songs ping-ponging back and forth between sweet and catchy vocals and noisy instrumentation. The specters of Taking Back Sunday and Green Day lurk around the corners of Idol’s playground.

At the same time, the album emulates “Eyes Without a Face” and “Dancing with Myself,” Idol’s synth-infused odes to touchstones like Jim Morrison and Elvis Presley. On occasion the two sides connect, as in “Evil Eye,” where moody Doors-in-the-desert verses meet soaring grunge choruses, and in the prowling guttural goth-country of “Lady Do or Die.” More often though, the stylistic disparity between the Idol-Tichy tunes and the Idol-Stevens songs fail to mesh, and Devil’s Playground never quite connects with the grand slam Idol clearly was aiming for.

Listen to "Lady Do or Die"

The fault, Idol said in his autobiography, is his. He admitted that he was insecure after his 12-year, post-Cyberpunk banishment to the pop culture desert, and that he relied too much on other people’s opinions on Devil’s Playground. He allowed Tichy to dictate arrangements of songs he had co-written. Idol also felt he was unfair to Stevens, requiring his right-hand man to play guitar parts demoed by Tichy note-for-note.

Tichy’s influence is most prominent on the two tunes that open the record. “Super Overdrive” and “World Coming Down” are propulsive and clangorous to the point of being speed metal. There’s nothing wrong with that, but the mix is claustrophobic. If the tunes had a little more space, they would swing like “Cradle of Love.” Idol also pushes his vocal range on this pair of metallic rockers. Gone is the sepulchral croon of “Eyes Without a Face.” In its place is a razor-blade gargle pitched midway between Roger Daltrey’s mid-'70s roar and Yosemite Sam’s bellow. Clearly the songs were meant to be a brisk one-two punch, but they falter from trying too hard.

By contrast, the pop rocker “Sherri,” composed solely by Idol, plays to his strengths. His vocal is relaxed and fun, the melody recalls late '70s melodic punk, and Stevens’ looping rockabilly-inspired solo smokes. First single “Scream” rides snapping percussion and chunky guitars, while Stevens reels out a grimy clarion call solo with ample tremolo. The album’s best tune is also its most uncharacteristic. “Cherie,” a paean to Idol’s ex Perri Lister, is jaunty folk-inflected soul, propelled by Stevens’ chiming tumbling fills which seem to channel Duane Allman.

Listen to "Cherie"

Devil’s Playground boasts three hits, two near-misses and a pair of failures, but aside from just plain weird efforts like the rollicking dysfunctional family holiday anthem “Yellin’ at the Xmas Tree,” the goofy compendium of horror clichés “Body Snatcher” and a truly bizarre and grimy cover of “Plastic Jesus,” a tune sung by Paul Newman as the titular hero of the 1967 prison drama Cool Hand Luke, Devil’s Playground features a pair of Idol/Tichy tunes that are decent rockers that turn too cacophonous and loud, and ultimately outstay their welcome: “Rat Race,” and the crunchy riff-driven “Romeo’s Waiting.” Also in the loss column is a rare misstep by Idol/Stevens, “Summer Running,” which starts out promisingly like a lost Cat Stevens tune until it's pummeled by the production.

Despite this muddled bloodbath Devil’s Playground emerges as a qualified success, thanks to the infectious “Sherri,” the lithe and folky “Cherie,” and “Scream,” a throwback to the hard-partying horndog Idol of the '80s. These songs in particular did exactly what they needed to do. They announced that Idol was back to stay, while illustrating the most prominent lesson to be gleaned on this playground: Idol is at his best when he’s having fun.

Billy Idol Albums Ranked Worst to Best

More From Ultimate Classic Rock