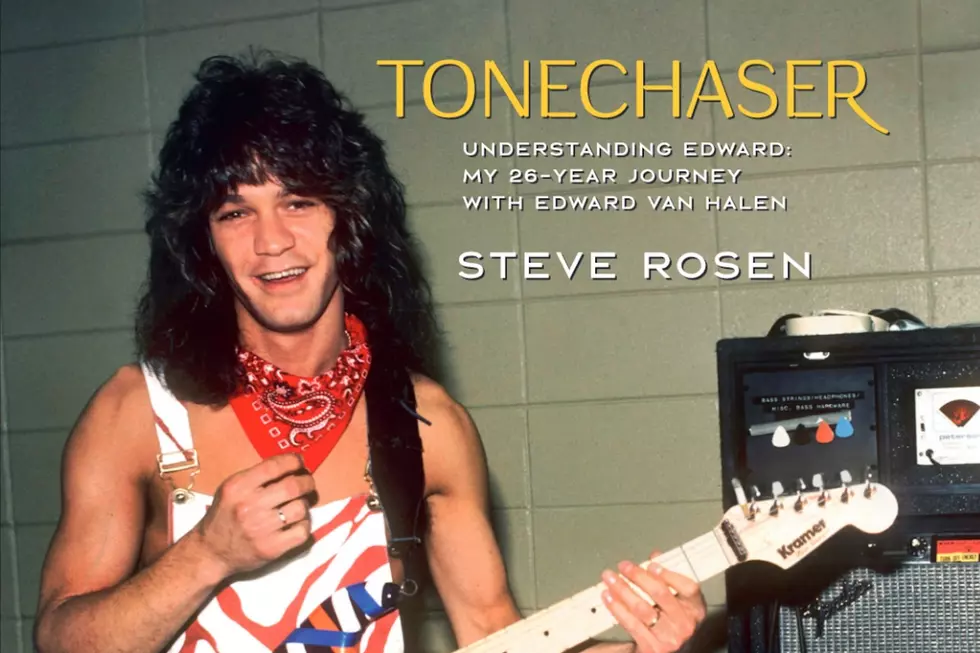

Did One Song Force the Collapse of Van Halen’s Original Lineup?

In May 1982, Van Halen released their cover version of “Dancing in the Street,” which would become a Top 40 hit and help steer their fifth album, Diver Down, to more than 4 million sales and No. 3 on the chart.

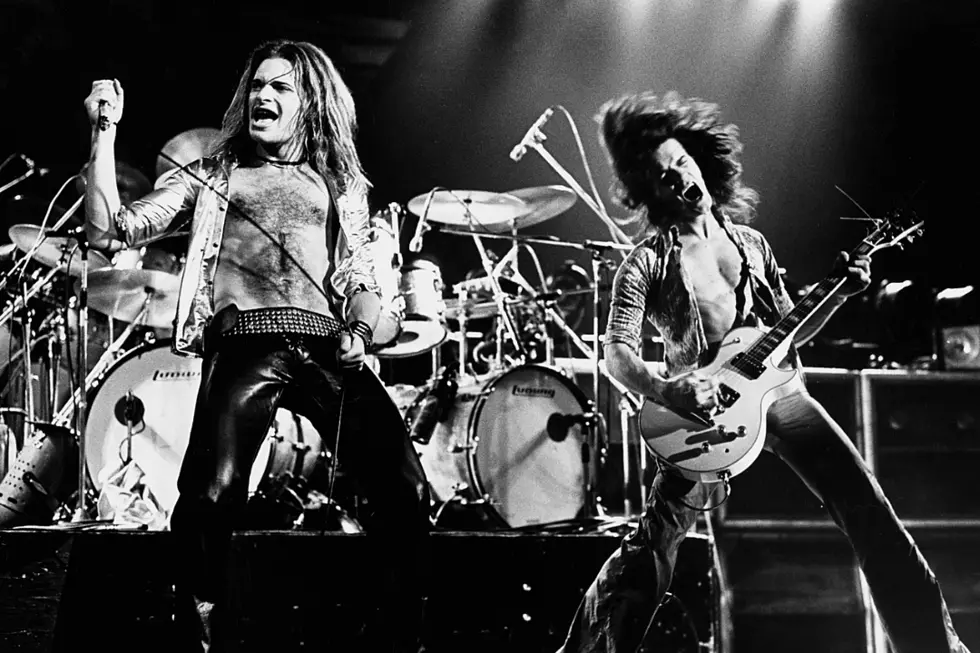

It was certainly a different take than the many other covers of the ‘60s track that was co-written by Marvin Gaye. While singer David Lee Roth delivered the lyrics in his trademark larger-than-life rock-star style, the most notable element of the music was an insistent synthesizer riff created by Eddie Van Halen. The song was an impressive but strange marriage – and, it seems, was to be the catalyst for an equally strange divorce three years later.

Tensions had been rising for some time between the band's leading men. The singer wanted to become even larger than life and even rockier, while the guitarist wanted his band to become as eclectic as possible. Van Halen had written the synth riff with an original song in mind, and the compromise of using it as part of a cover version was not a happy one.

Even on its release the parties differed. “It sounds like more than four people are playing, when in actuality there are almost zero overdubs,” Roth said. “That’s why it takes us such a short amount of time [to record].” But, Van Halen argued, “It takes almost as much time to make a cover song sound original as it does writing a song. I spent a lot of time arranging and playing synthesizer on ‘Dancing in the Street.’”

Listen to Van Halen's 'Dancing in the Street'

“I didn’t want to be halfway there with someone else’s stuff,” Van Halen said in 2014. “Diver Down was a turning point for me, because half of it was cover tunes. I was working on a great song with this Minimoog riff that ended up being used on ‘Dancing in the Street.' It was going to be a completely different song. I envisioned it being more like a Peter Gabriel song instead of what it turned out to be, but when [producer] Ted Templeman heard it, he decided it would be great for ‘Dancing in the Street.'”

The story behind the album was one of compromise, as well. The band wanted to slow down after its Fair Warning tour in 1981, and the idea of releasing a standalone single to plug the gap was suggested. The result was “(Oh) Pretty Woman,” which did so well that the band’s label immediately required an album, and so Diver Down was recorded and a tour booked, instead of the hoped-for escape from that very cycle.

With no time to recharge, the tensions inevitably increased. By the end of the Diver Down experience, Eddie Van Halen was determined to avoid the kind of compromises he’d previously endured. He wasn’t just fighting with Roth, but also Templeman, and an us-and-them situation developed with Van Halen and engineer Donn Landee on one side, Roth and Templeman on the other.

“The bottom line is that I wanted more control,” Van Halen said later. "I was always butting heads with Ted Templeman about what makes a good record. My philosophy has always been that I would rather bomb with my own music than make it with other people’s music. Ted felt that if you redo a proven hit, you’re already halfway there.”

Van Halen and Landee hit on the idea of building their own studio – not with the original intention of creating finished works, but to “show Ted that we could make a great record without any cover tunes and do it our way.” However, the project grew arms and legs to the point that, when 5150 Studios was completed, it became the location of every Van Halen recording since.

“I certainly didn’t know how to build a studio,” the guitarist recalled. “It was all Donn’s magic. … We had grown really close and had a common vision. Everybody was afraid that Donn and I were taking control. Well … yes! That’s exactly what we did, and the results proved that we weren’t idiots. When you’re making a record, you never know if the public is going to accept it, but we lucked out and succeeded at exactly what my goal was. I just didn’t want to do things the way Ted wanted us to do them. I’m not knocking Diver Down. It’s a good record, but it wasn’t the record I wanted to do at the time.”

He described the band’s next album, 1984, as “me showing Ted how you really make a Van Halen record.” The first track recorded at 5150 was “Jump,” which Van Halen forced through on the strength of his personal vision, supported by Landee. Its synth-heavy approach was to dominate the entire groundbreaking LP, and the single gave the band its only No.1 hit -- apparently proving the guitarist correct. “Once Ted heard that song, he was full-hog in,” Van Halen recalled. “When I first played ‘Jump’ for the band, nobody wanted to have anything to do with it. Dave said that I was a guitar hero and I shouldn’t be playing keyboards. My response was if I want to play a tuba or Bavarian cheese whistle, I will do it.

“As soon as Ted was on board with ‘Jump’ and said that it was a stone-cold hit, everyone started to like it more. But Ted really only cared about ‘Jump.’ He didn’t care much about the rest of the record. He just wanted that one hit.”

With the music seeming to be going further away from what Roth wanted, he instead tried to enforce his personality on the band's videos. His intention for the “Jump” clip was to have him seen in a wide range of rock-star moments, which producer Robert Lombard felt worked against the intimacy of the performance scenes that went on to inspire an entire generation of copycat videos. After trying to have his concerns taken into consideration, Lombard found himself fired. “‘You don’t go behind Dave’s back’,” he remembered being told. “‘Here’s your check, never want to see you again.’ That video won the award for best performance video at the first VMAs. And I still don’t have my award.”

Listen to Van Halen's 'Jump'

The success of 1984 put Eddie Van Halen in the driving seat, and left Roth less convinced that he wanted to sit alongside. In response, he began developing a solo career, and, along with the Crazy From the Heat EP, he developed a movie script with the same title in which he planned to star.

“Since my very first days in with the band 11 years ago, I have always had the feeling that one day I would wake up in a cold hotel, all the rooms would be empty and I would be stuck by a phone with a busy signal,” the singer said ominously in an interview. “From the first day. Nothing has changed.”

In a later interview he predicted the band would "be going back in the studio and start arguing again and we all look forward to that. ... We have a lot of respect for each other and get along quite well, actually.” That wasn’t to be. In March 1985, he and Eddie Van Halen staged something of a summit meeting, where it became clear their ambitions for the band were some distance apart. The guitarist later said the conversation ended in an attempt to discuss Roth’s movie. “I can’t work with you guys anymore,” Van Halen quoted Roth as having said. “I want to do my movie. Maybe when I’m done, we'll get back together.”

Several months later, the truth came out. “The band as you know it is over,” Van Halen reported. “Dave left to be a movie star. … He even had the balls to ask if I’d write the score for him. I’m looking for a new lead singer ... it’s weird that it’s over. Twelve years of my life putting up with his bullshit.”

But it wasn’t over, and perhaps it’s still not – but there were to be many more twists and turns in the Van Halen story. Perhaps there would have been fewer without that fateful cover of “Dancing in the Street.”

Van Halen Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock