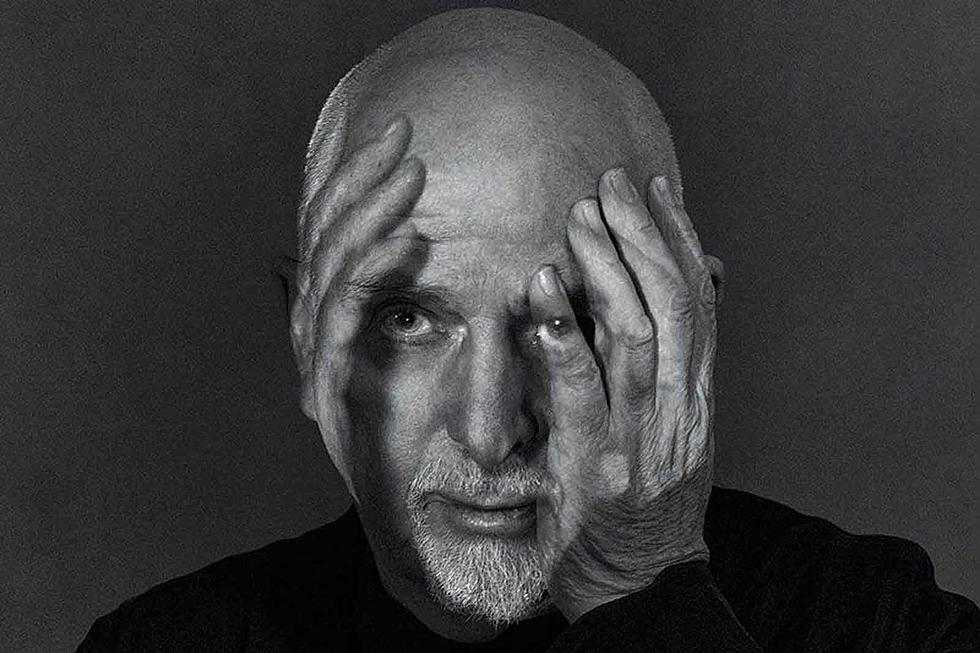

How Peter Gabriel Found His Art-Rock Voice on His Third Album

Peter Gabriel left Genesis in 1975, bowing out at the band's creative zenith to pursue the stylistic and personal freedom of a solo career. But it took the art-rock legend three albums to figure out his musical identity.

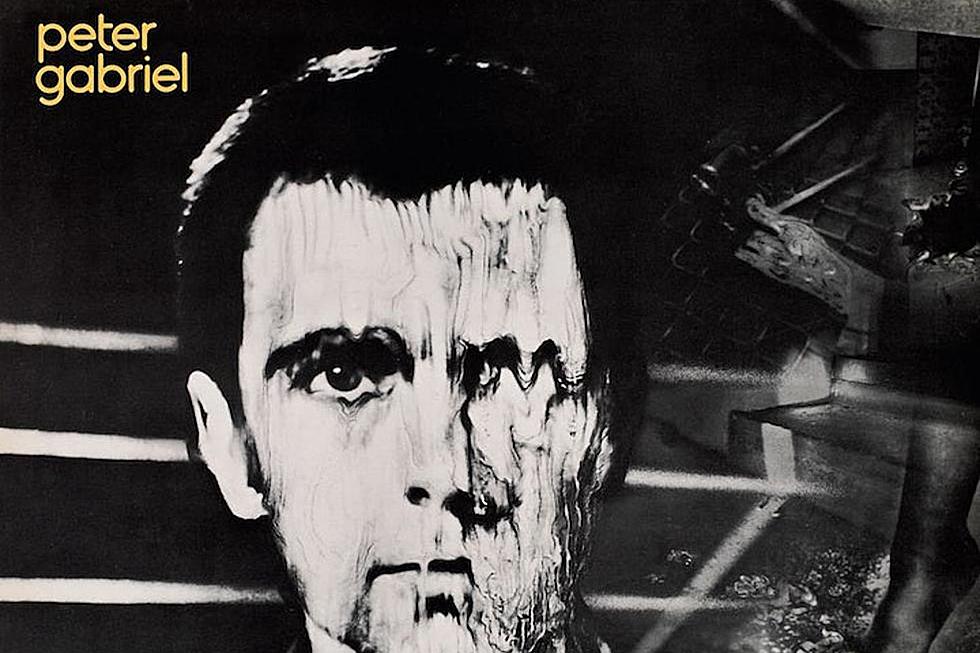

His self-titled 1977 debut (best known as Car) found the songwriter dabbling in everything from blues-rock ("Waiting for the Big One") to barbershop quartet ("Excuse Me"), and his second LP (commonly labeled Scratch) embraced a darker, more textured aesthetic with production from King Crimson mastermind Robert Fripp.

Rewarding albums, no doubt – but in retrospect, they sound like a man so emboldened with ideas, he couldn't focus on any particular one long enough to refine it. That problem ceased with his first true masterpiece, known as Melt, which was released on May 23, 1980.

The clarity of purpose is evident from the very first cracking snare of "Intruder," wherein Gabriel embodies a stalker over dissonant keyboards and the menacing thud of former bandmate Phil Collins.

Like Scratch before it, Melt is built on brooding atmosphere – but its balance of off-kilter experimentation and melodic focus offers an edge over its predecessor.

There's no quirkiness for the sake of quirkiness here, not a single wasted second. Singles like the Kate Bush-boosted synth sing-along "Games Without Frontiers" and throbbing rocker "I Don't Remember" form a brilliant intersection between art-rock and modern pop, mostly because the songs are so tight and carefully constructed.

Producer Steve Lillywhite and engineer Hugh Padgham (most famous for his "gated reverb" drum sound) bring a sonic sparkle – a striking sense of space and vibrancy – with tones as pleasing through a pair of headphones as they are through speakers.

Listen to Peter Gabriel's 'Intruder'

"‘Modern’ was good," Gabriel told Uncut of the production in 2012. "But ‘different,’ really. Particularly with the third album, I was trying to find my own path. I worked with these young guys, Steve Lillywhite and Hugh Padgham, who’d done new-wave-y, punky, XTC-type stuff. It was this tougher, more skeletal, edgier music, and it seemed very exciting. I liked XTC a lot. In fact, I heard 'Making Plans For Nigel' this morning, and thought, ah, yeah!"

Atlantic Records, who distributed Gabriel's first two albums in the U.S., were famously displeased with Melt upon first blush, calling the songs "commercial suicide." The label came crawling back after the LP then hit No. 1 in the U.K., begging for the release rights, but Gabriel moved forward with American label Mercury.

"We made two terrific solo albums with Peter, but then he delivered an album which some people were not so crazy about," Atlantic executive Ahmet Ertegun wrote in 2001. "So Jerry Greenberg decided to let him go, and we released him from his contract. In retrospect, that was a big mistake. Peter is a great, visionary artist."

Gabriel told Sounds in 1980 that he heard Ertegun "thought it was quite arty, but the A&R department told him it was undesirable, too esoteric. An Atlantic guy who came over to hear us in the studio asked me to make one song ['And Through the Wire'] sound more like the Doobie Brothers. I said, 'No.'"

Melt is not only Gabriel's finest front-to-back album; it also marks his first foray into political writing, with closer "Biko." The sparse, meditative track – built primarily around the frontman's bold yelps, Larry Fast's bagpipes and Collins' powerful drumming – was written in honor of slain South African anti-Apartheid activist Steven Biko. It's one of the singer's most resilient anthems, a rainbow after an album-long thunderstorm.

Melt is the crucial pivot point in Gabriel's discography, his first – but not final – brush with perfection. He never made another album like it, and neither has anybody else.

See Peter Gabriel and Other Rockers in the Top 100 Albums of the '80s

More From Ultimate Classic Rock