Why Paul McCartney and Wings Fell Apart After ‘Red Rose Speedway’

Paul McCartney and Wings' Red Rose Speedway was supposed to be a double album, something indicative of a band at the peak of its powers. Instead, Wings disintegrated not long after, as both drummer Denny Seiwell and guitarist Henry McCullough left. It was as shocking as the resulting studio effort was uneven.

Seiwell had been with McCartney since 1971's Ram, creating a sturdy backbone for the early days of Wings that followed. The free-spirited McCullough joined in time for the group's biggest early successes, including the chart-topping "My Love" and the James Bond movie theme "Live and Let Die." Together, they'd piled into a van for the very first, remarkably intimate Wings tours – conducted from aboard an open-topped bus.

"It was our version of the Magical Mystery Tour," McCartney told Classic Rock in 2016. "We decided to start from the ground up, and try and build a band like everyone else did. It starts with everyone getting to know each other – do small gigs and start from square one. But of course, being us, we just did it the craziest way. Anyone else would have booked hotels and booked gigs but oh, no! We didn’t bother with that. We just took the van. It was a kind of romantic notion. We got on the motorway and when we saw a place we liked, we stopped."

That was the summer of 1972. Out on the road, they bonded. Everything fell apart, however, once they returned to the studio. Red Rose Speedway arrived on April 30, 1973, and by then fissures were already opening up. Ironically, "My Love" – their gold-selling early breakthrough moment – held the seeds of their future split.

Though the single was released under the band's name, McCartney had worked out everything for "My Love" – even the guitar solo. The late McCullough, however, had other ideas.

"Paul had this particular thing that he wanted me to play. That was the point of no return," McCullough said in 2011. "I said: 'I'm sorry; I can't do this. I have to be left as the guitar player in the band. I want to have my own input, too.' He says, 'What are you going to do?' I didn't know. I simply said: 'I'm going to change things.'"

McCullough eventually fought for, and won, the chance to play the ballad's searing guitar solo his way – but, in the end, something else was lost: the sense that Wings were really a band, and not just a backing group for McCartney. A pay structure that reportedly amounted to nothing more than a small weekly stipend didn't help matters, either.

"We had an interesting moment on the session where we were going to cut it live at Abbey Road Studios, and the guitar player came over to me right before the take – we knew what we were going to do as a band, and the orchestra was arranged – and he said, 'Do you mind if I try something different on the solo?'" McCartney later told Billboard's Timothy White. "It was one of those moments where I could have said, 'I'd rather you didn't; stick to the script,' but I thought he sounded like he's got an idea, and I said, 'Sure.' He came out with the really good guitar solo on the record; it's one of the best things he played. So, that was like, 'Wow.'"

Listen to Wings' 'My Love'

The solo was put to tape as a first-take live performance, and McCullough admitted to being both "half-terrified, half-excited. I just started playing, and that's how it turned out – just as you hear it. That flabbergasted Paul, and there was just silence for a while. I thought: 'Uh oh, I have to do it again.' Paul came over and said: 'Have you been rehearsing?' I liked to have that freedom. I wanted to put my cards on the table. He asked me in the band, but I didn't want him to tell me what to play."

At the same time, stalwart Wings member Denny Laine said there were growing tensions between McCartney and his label bosses, who were pushing for a more concise project after Wings' 1972 debut Wild Life flopped – and between McCartney and second producer Glyn Johns.

"He and Paul didn't hit it off at all," Laine said of Johns in Blackbird: The Life and Times of Paul McCartney. "Paul always likes to be his own producer anyway, but at least if he's going to bring one in they've got to be able to see Paul's point of view."

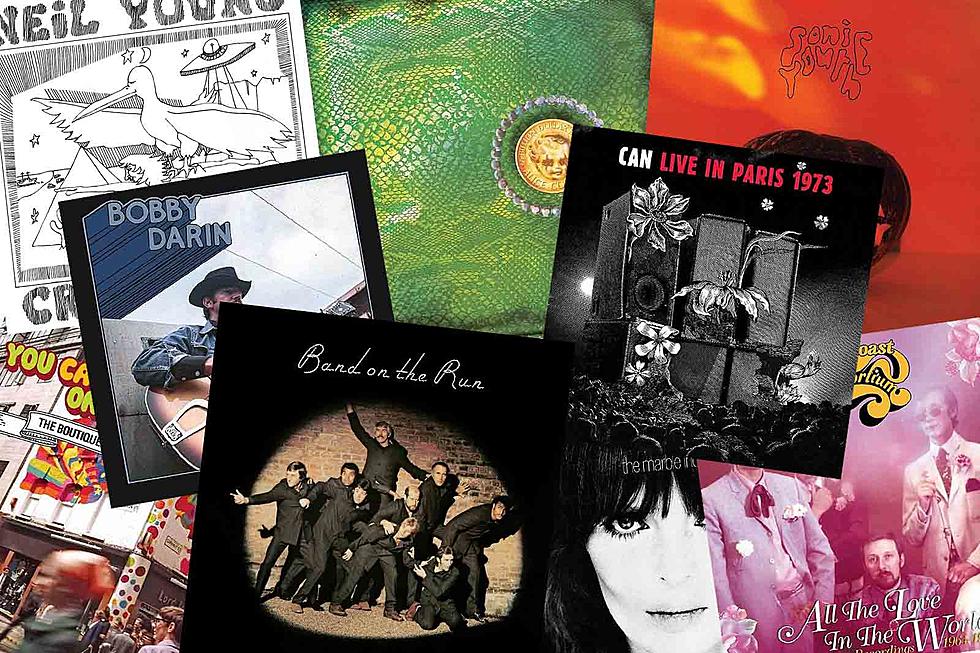

Red Rose Speedway tends to reflect that turbulent, pressure-filled atmosphere. McCartney's continued struggles with the final track listing meant that songs from the earlier sessions for Ram bobbed back to the surface ("Little Lamb Dragonfly" and "Get on the Right Thing"), and other new tracks were left to future live albums or B-sides ("Soily," "Country Dreamer," "Mama's Little Girl") or Wings solo records (Laine's "I Would Only Smile," Linda McCartney's "Seaside Woman"). Others were simply discarded.

In the end, the weakened, suddenly ballad-heavy Red Rose Speedway – which, Laine once lamented, had begun life as "more of a showcase for the band" – no longer had any sense of purpose. Linda McCartney described the results as "such a non-confident record," in Band on the Run: A History of Paul McCartney and Wings. "There were some beautiful songs. There was 'My Love,' but something was missing. We needed a heavier sound. It was a terribly unsure period."

As with Ram, a studio concoction which been had credited to the McCartneys as a duo, Red Rose Speedway boasts a few Beatles-esque moments – most notably an 11-minute closing medley. "Get on the Right Thing," bolstered by one of Paul's classic Little Richard-style vocals, likewise has an episodic flair that recalled some of the best-known elements of the Abbey Road era, but it found a home near other songs that don't possess nearly that much gumption. The addition of something like "Live and Let Die" might have given the project more lift, but in the end Red Rose Speedway sounded like what it was: a hodgepodge of ideas, without a delineated focus.

Or, put more succinctly, the sound of a band breaking up.

Listen to Wings' 'Get On the Right Thing'

By the time Wings gathered for sessions in Lagos for what would become Band on the Run, the lineup was whittled down to Paul, Linda and Denny Laine. McCullough split first, during the first rehearsals for this multi-platinum follow up. Seiwell was out the door next.

"Henry liked to play things differently every time; he had a little jazz in him," Seiwell said in 2013. "And Paul kind of pushed Henry into the corner about playing his part the same way, every time we played – the solo from 'My Love,' as an example. I think Henry had just had enough of it, and he left. I had no plans on leaving, but at that point I felt like we had really gone to great lengths to become a band – and, to go down to Lagos and record Band on the Run without Henry, it was just going to be a bunch of overdubs again like Ram. I tried talking to Paul into maybe postponing it for a month, and breaking in another guitar player, so we could be more organic about recording. He didn't go for that."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, most of Wings seemed to look back on this period with regret. Red Rose Speedway "has its moments, but nothing approaching the impact of the band in person," McCartney said in The Beatles: Off the Record 2. "After I had heard Wild Life, I thought, 'Hell, we have really blown it here.' And the next one after that, Red Rose Speedway, I couldn't stand."

Meanwhile, Seiwell's sudden exit had been bittersweet. He had been there for Wings' first stirrings, and had seen the band through its earliest triumphs, but couldn't get past a financial situation that kept the other members from sharing equally in the band's successes. Continuing legal issues with the breakup of the Beatles, he added, kept everything in limbo.

"I was really pushing for an agreement; we were all working on a handshake," said Seiwell, who returned to jazz, his first love. "We had no contracts or anything like that, in those days. I don't think we could have even had one that was legal, because of the Apple receivership and the court case that was going on at the moment. So, I was there at the best, and the worst time, if you will."

McCullough, however, said he never looked back. The guitarist later reunited with Joe Cocker, with whom he had appeared at Woodstock, then recorded an album for George Harrison's Dark Horse label. He'd go on to work with Donovan, Roy Harper, Eric Burdon and Ronnie Lane, while establishing a more sporadic solo career.

"It just wasn't going to work out for the rest of us in Wings," McCullough said a year before suffering a damaging 2012 heart attack that eventually killed him. "Unless, of course, you had an apron on, if you know what I mean."

Beatles Solo Albums Ranked

You Think You Know the Beatles?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock