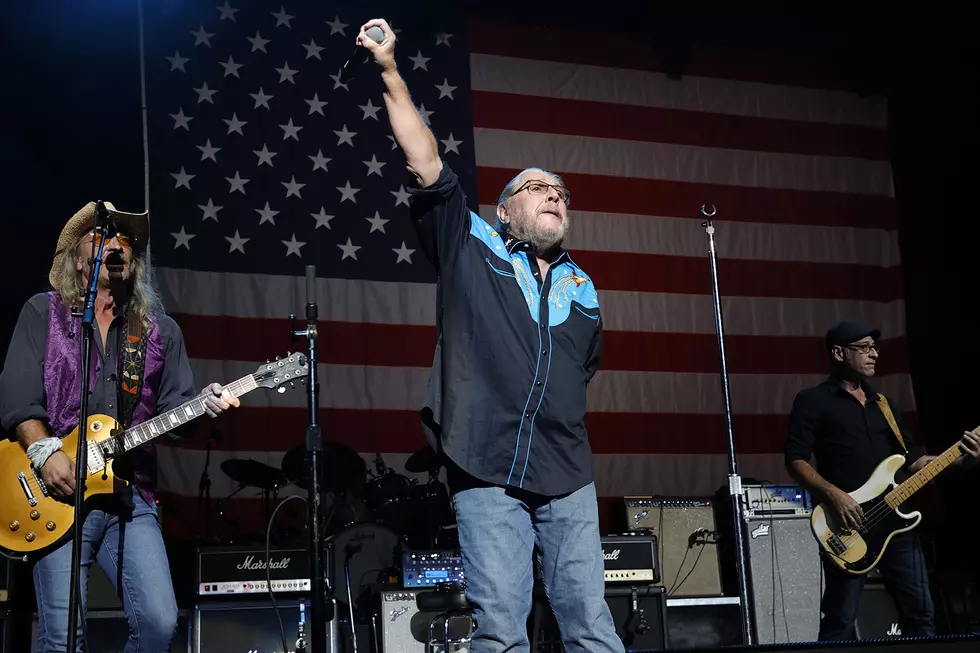

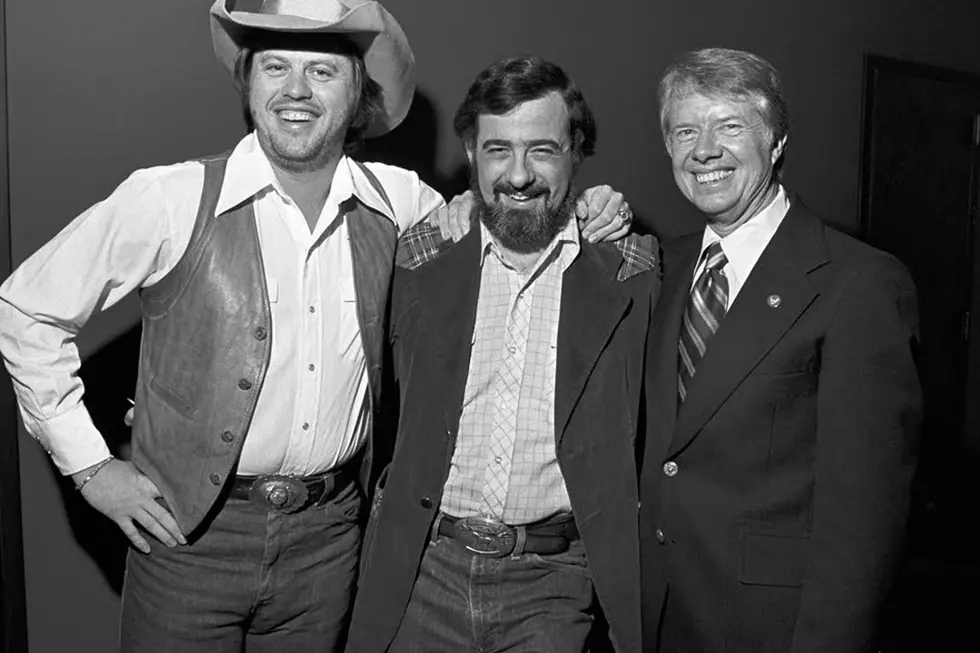

Marshall Tucker Band’s Doug Gray Talks New Live Album, Touring Europe and More: Exclusive Interview

The Marshall Tucker Band recently opened their vaults and released Live in the U.K. 1976, a snapshot of the iconic southern rock outfit's original lineup in peak form. After pressing "play," you get an immediate reminder that in the '70s it was customary for bands to gig and gig and gig some more. Culled from shows in four different cities -- London, Manchester, Birmingham and Glasgow -- these newly unveiled performances capture a band as fluid as it was tight, and it's obvious that this group of musicians had, by this point, logged countless hours playing together.

At the same time, as singer and sole remaining original member Doug Gray tells Ultimate Classic Rock, he and his bandmates may have been road-tested, but they were green when it came to overseas travel and the business side of the music industry. They actually had no idea they had a European following in the first place. Sure, the crowd noticeably lights up when the band breaks into late guitarist (and principal songwriter) Toy Caldwell's classic "Can't You See," but Gray recalls being knocked out by the enthusiasm of audiences across the board.

Thanks to a warm, full mix courtesy of engineer Buddy Strong, U.K. 1976 brings that classic '70s live-album vibe rushing back, but Strong also gives such striking clarity to the original tapes that the album sounds like it could have been recorded yesterday.

The new live album documents the band's first European tour. What's the thing that stands out the most in your memory about that trip?

Ridin' around in a big pink bus. You should've seen us going down the highway. Every couple of days, you'd have to stop the bus at a payphone in order for everybody to call home and check in. So you had 18-26 people and each person had to have as long as it took on the payphone. I'm a Vietnam veteran, so I'm pretty used to being around people with guns, but the first few times we saw security guys standing there at airports and border crossings with guns, it was kind of a strange thing to see. But as far as the music goes, it was nothing but fun. The response that we got was unbelievable. It was like all of a sudden Elvis had arrived or something. That was kind of weird for us.

The press release for the album says that you guys didn't now what to expect, and that you didn't know how well your music would connect with audiences overseas.

Right. It was a little overwhelming just to feel that they paid attention. They knew the music as well as the people in the States. And we sold out in every city. We knew that the band must've been good -- of course, we were on the road 300 days a year then. We'd already played a lot of the bigger places and nicer, smaller halls that had reputations back in the States. With a place like the Hammersmith Odeon that you'd heard of, it was like playing Madison Square Garden all over again. Musicians like to work toward playing places that have notoriety. So just being able to walk into a place like that and experience it after hearing so much about it, it was like connecting with a part of history. And that history makes us the kind of band that we are today. We're still able to go work and do 150 shows a year.

When you listen to the record, the audience cheers louder when you guys start to play "Can't You See." In 1976, how would people in Europe have been exposed to your music? How would your label and promoters have marketed you over there?

It was kind of hilarious. We knew that our music was being played in Japan, but we had no idea about Europe. It was being played on a lot of American military radio and on album-oriented stations, but we didn't have a clue that our records were selling as well in some of these places. At that point in time, we were young to the business. We were still stupid to the places music can go. Over in Europe, the record companies were marketing us as just a rock 'n' roll band from the south. That term "southern rock" hadn't even really been invented yet.

So in 1976, you hadn't heard the term "southern rock" yet?

No, it wasn't slapped on us or the Allman Brothers or Skynyrd or anybody yet. It was just, "Here's a bunch of guys from the south." But of course we stood out in England and even in certain parts of the United States. The funniest thing was sweet tea, because we drink our tea sweet. In England, there was no sweet tea, and we looked at people like they were crazy. And then it was like, "What's grits?" So they were laughing at us in England as much as we were laughing at them.

So people would look at you funny ordering sweet tea in parts of the U.S. too?

Oh yeah, especially in the northeast: "You put what in what?!" But over there, they were already less prejudiced than we were.

You mean less prejudiced compared to the U.S., or less prejudiced in terms of what they were expecting from you being from the south?

I was expecting more prejudice [overall] in the United Kingdom and Germany, but when we went we had everybody [a mixed crowd] coming to our show. These days, that happens every night because we have such a wide variety of musical ...

You guys put a lot of ingredients in the sauce -- the gospel thing, the boogie thing ...

You're making my job easy! Yeah, we took B.B. King back out on the road opening shows for us when he was having a down period. I mean, let's face it, everybody has their up and down periods. We were sitting around one day in our office in New York and one guy said, "You're drawing 20,000 people. Who do y'all want to open for you?" I said "Let's have B.B. King and his orchestra come out," and everybody looked at each other and said, "By God, that's a great idea!" I mean, those guys looked at me a little bit like I was stupid, but evidently I know a little bit about music. That comes from liking and loving and listening to music. Go back and listen to the Pointer Sisters -- that's what I used to listen to on the bus as it was going down the road. I was one of the first guys to go see James Brown play for an all-black audience when I was 8 or 9 years old in Spartanburg, S.C.

What was the venue?

Spartanburg Memorial Auditorium.

So you were one of the only white kids there.

Me and one of my friends snuck in and got in to see it. And it was unbelievable.

How did that 1976 trip open your eyes musically?

There were a lot of musicians there. I saw Ringo Starr sitting in a restaurant right outside our hotel. You know, that's pretty heavy. When you see people who have traveled the entire world and have seen and done more than you have, you want to do a little bit extra. And then most of the guys in the recording truck were musicians. All I wanted to do was go back and listen to a little bit of what we'd recorded, but there were so many musicians packed in that thing that you couldn't get in there. As far as people wanting to come up and jam with us, we had Bonnie Bramlett of Delaney & Bonnie traveling with us, and a group named Grinder Switch from Macon, Ga. We didn't know many musicians in Europe, but there were always like 20 or 30 musician types at the shows.

So why now on releasing this album? Where were the tapes, why did they sit on the shelf for so long and how long had it been since you'd heard them?

We pull a lot of different stuff out of the box and listen to it every so often. A lot of it's already been digitized because we're always looking towards the future. And we also like to release live versions of songs that people will bring up to me on the road, like "Why do y'all never play that song anymore?" It's impossible to play over 350 songs. That'd be quite a long show!

Other than one guitar solo of Toy's, this album doesn't get into these long extended solos that you hear on albums like At Fillmore East or The Song Remains the Same. And most of the songs are really concise. How accurately does this album recreate what it was like to be at a Marshall Tucker show during that year?

We had time restrictions at those shows in Europe. But even today "Can't You See" or any of our album cuts from that period can stretch anywhere from 35 minutes to an hour.

Live in the U.K. definitely sounds like it was recorded in 1976, but it also sounds startlingly crisp.

I can pat myself on the back for that.

So you're the one overseeing that part of the process?

I make sure that every one of these releases goes out with a quality sound treatment. When I listen back to a piece of tape and the engineer looks at me and says "I can fix that," I'm thinking, "You don't go back and put a smile on the Mona Lisa." I hate to compare the two, but the engineer will say, "We've got machines that can take that bad note out," and it's almost like it meant nothing. Well, everything meant something to all of us. Probably 95 percent of the music we played was really, really good, but you don't get rid of that other 5 percent because you want to give everybody 100 percent of that same memory from that night.

You didn't go back and fix things, but you did pick different songs from different shows. How did you select the performances?

When I'm sitting and listening, I close my eyes and here I am listening to myself from 40 years ago, listening to the other guys in the band who've passed on, and I kind of put myself back on that stage. I have that ability to close my eyes and go back to that night, that show, that backstage area, and to riding around in that bus getting from place to place in every country. And so the music should be just as good as my memory of it is. I'm very fortunate that way. All it took with these tapes was to make it a little bit crisper.

Where were you guys in terms of your relationships with each other at that time?

We had no idea what we were doing, and we were already in this business for five years. We made decisions and we continued on with our business, but we had no idea what the next step was. We'd had a couple of gold records and got excited, but who can know what's ahead? It's kinda hard for me to say how the band was getting along because we never argued. It was never like, "You're gonna have to play this lick" or "You sucked on that lick" or "You were really bad" or "Why don't you change this around?" because we all created this together out of high school and -- in me and Toy's case -- Vietnam. Hey, we were just happy to be there.

See the Top 100 Albums of the '70s

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's Worst Snubs

More From Ultimate Classic Rock