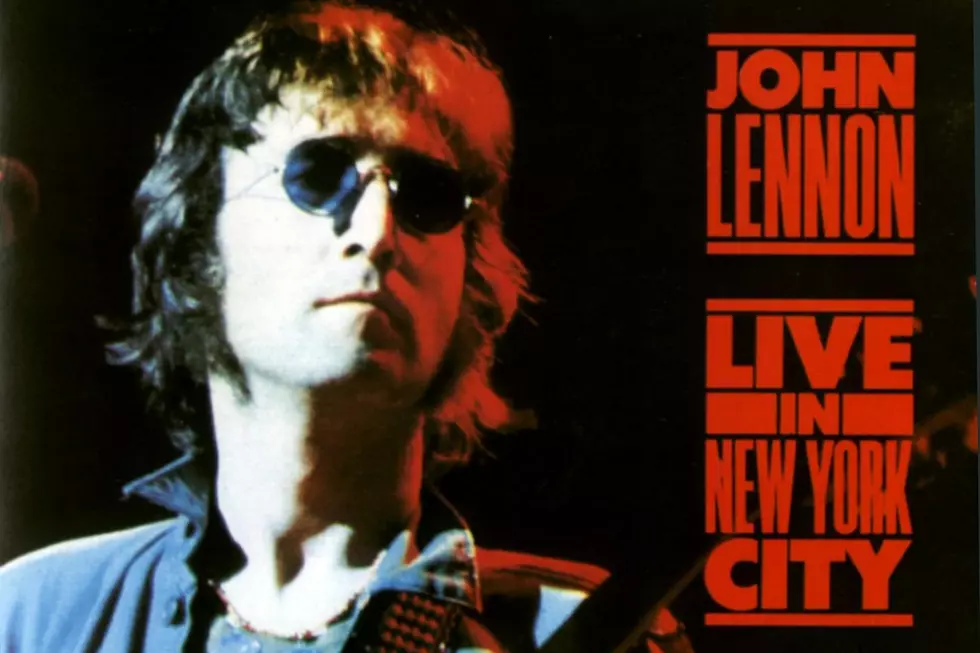

Why John Lennon’s ‘Live in New York City’ LP Was So Frustrating

The sloppy, posthumous Live in New York City LP documents John Lennon's final full concerts — but rather than reflecting his musical genius, it reminds of wasted opportunities.

Despite its failure on a creative level, the music served a good cause. The album, released Feb. 10, 1986, samples the former Beatle's pair of Plastic Ono Band gigs at the August 1972 "One to One" festival. The Madison Square Garden event, which also featured Stevie Wonder and Roberta Flack, raised money for Staten Island's Willowbrook State School for children with intellectual disabilities — an institution whose horrifying conditions were revealed in a Geraldo Rivera expose earlier that year.

"[Rivera] came all the way to San Francisco to meet us," Yoko Ono later recalled. "He convinced us to do this. Without him, it wouldn't have happened."

Lennon and Ono had already played multiple benefit shows — like a 1969 UNICEF show in London — operating under the moniker Plastic Ono Band. They worked with a shifting crew of musicians — including Eric Clapton, bassist Klaus Voormann and future Yes drummer Alan White, all of whom appeared during their set at the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival, chronicled on the Live Peace in Toronto 1969 album.

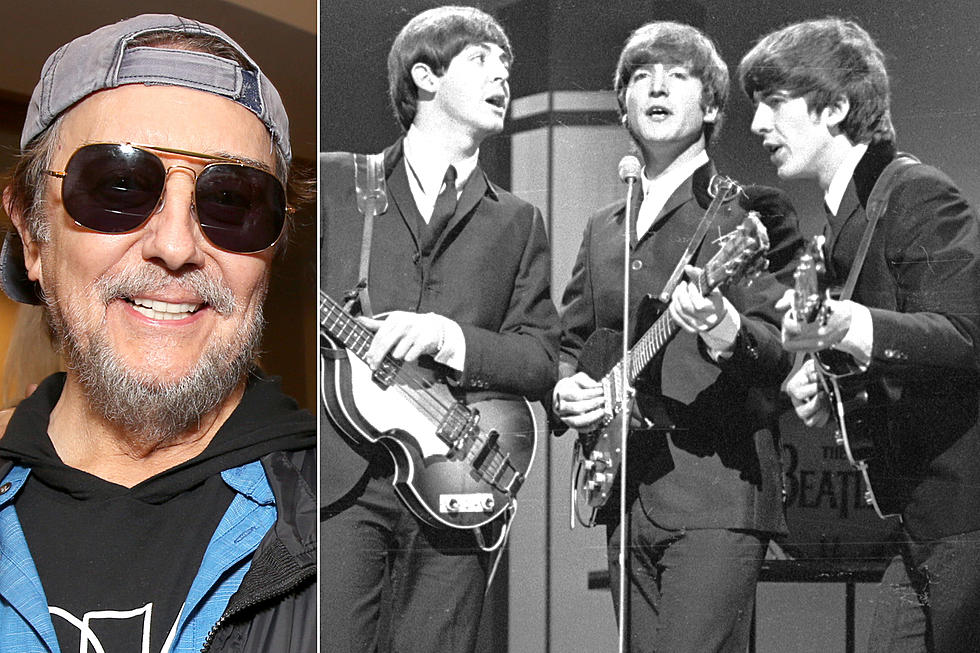

But the couple took a much different approach for "One to One": Instead of hastily assembling a one-off supergroup, they recruited a semi-obscure New York City psych-rock act, Elephant's Memory, to serve as their backing band.

According to that group's bassist, Gary Van Scyoc, the members met Lennon and Ono in September 1971, after they'd moved to New York City and immersed themselves in local culture and political activism. Elephant's Memory had recorded a live set for a Long Island radio station, and that tape supposedly wound up with counterculture leader Jerry Rubin, who then passed it along to Lennon.

"John listened and just loved the tape," Van Scyoc told Classic Bands. "He just heard all the ingredients that he liked. So he was very interested and apparently decided to come down to one of our rehearsals at a studio called Magne Graphics down in Greenwich Village. ... He stopped in one night. He didn't even make it into the room. Our road manager was apparently out there talking to him for awhile. We wouldn't really let anyone come in to our rehearsals 'cause we were trying to write songs at that point. It was kind of closed. So [our road managers] were trying to come in to tell us John Lennon was outside. We just thought they were putting us on. I think we kept him waiting for about an hour before he finally made his way in."

Van Scyoc recalled Lennon being "very cordial" and decked out in a "white suit like he had on [the cover of] Abbey Road." After jamming early rock songs "for hours and hours and hours," they decided to capitalize on their chemistry and "merge" the two projects: "Yoko was quick to speak up and say, 'Oh, POEM, Plastic Ono Elephant's Memory.'"

Elephant's Memory became an integral part of Plastic Ono — even if they played on some of Lennon's worst-received albums. First, they assisted in the studio portion of the 1972 double-LP Some Time in New York City. In April and May of that year, Lennon produced and contributed to the band's second self-titled record, and they all later worked on Ono's sprawling Approximately Infinite Universe.

The "One to One" shows — and, by extension, Live in New York City — should have found Lennon settling into a groove, working with a consistent backing band (plus drummer Jim Keltner here). But the recordings, as evidenced by the frontman's scattered comments during the show, are a mess — it often sounds like they're trying to gel in real time, and Lennon's vocals often sound bored and perfunctory.

"Let us pray the choir comes in on time," he says to introduce a ragged "Instant Karma!" (Afterward, he assures the audience, "We'll get it right next time.") On a clunky take on the Beatles' "Come Together," he continuously confuses his own bizarre lyrics. Following a clumsy drum-roll close on grinding blues-rocker "It's So Hard," he appropriately tells the crowd, "Welcome to the rehearsal."

Listen to John Lennon's 'Come Together' From Live in New York City

There are flashes of Lennon's classic charm, particularly when the music stops. "This song is another song from one of those albums I made since I left the Rolling Stones," he tells the crowd before "Mother." But it's not enough to make Live in New York City essential beyond the completists.

It's also important to keep context in mind: Lennon had been an infrequent live performer since the Beatles' final tour in 1966, and "One to One" wasn't part of a larger run. But according to Van Scyoc, it was intended to be, had Lennon not been caught up in a lengthy immigration struggle.

"We couldn't [tour] because of the Green Card situation," Van Scyoc said. "That was the deal. We were gearing up to do it. The way that John looked at that performance ["One to One"] … we'd been gearing up and rehearsing at [the Fillmore East] for weeks, for a tour is what we were hoping for. There was hopefulness at that point that he was finally going to get the Green Card. We had been buying equipment for months. We were gearing up for a tour."

Lennon's immigration headache continued until 1976 — and he addressed that frustration in a radio interview two years earlier.

"I love it, and that's why I'm fighting so much to stay here, so I can be in New York," he said. "Maybe they could just ban me from Ohio or something. Nothing against Ohio. I'd like to live here. I don't harm anybody. I've got a bit of a loud mouth — that's about all. I make a lot of music. That's what mainly I do. I'm either making music, watching TV or listening to the radio. Occasionally I get into a little spot of trouble but nothing that's going to bring the country to pieces. I think there's certainly room for an odd Lennon or two here."

Live in New York City finally emerged in 1986, six years after Lennon's death, with Ono supervising production of an album and home video. And even if many fans were let down by the project, it still served a bigger purpose: helping Lennon's widow continue to grieve.

"It was pretty emotionally difficult for me to go through all the frames," she said. "But also I kept saying, 'John, it was great! Do you see this?'"

The Best Song From Every John Lennon Album

See John Lennon in Rock’s Craziest Conspiracy Theories

More From Ultimate Classic Rock