When John Lennon Went Off the Deep End on ‘Some Time in New York City’

John Lennon's move to New York City coincided with a political shift leftward and, perhaps not coincidentally, lingering issues with immigration. The result was one of his most determinedly topical, most critically reviled and most often-ignored solo projects.

Some Time in New York City, a double album released on June 12, 1972, followed Lennon's mantra that the best songs were those where you simply "say what you want to say and put a backbeat to it." He had long been obsessed with getting songs out as quickly as possible, memorably having written 1970's "Instant Karma" in the morning and recorded it later that same day. This album was the natural outgrowth of this impulse, a recording focused on the issues of that very moment in time — ripped, as they say, right from the headlines. Unfortunately, those old dailies have become yellowed and frayed.

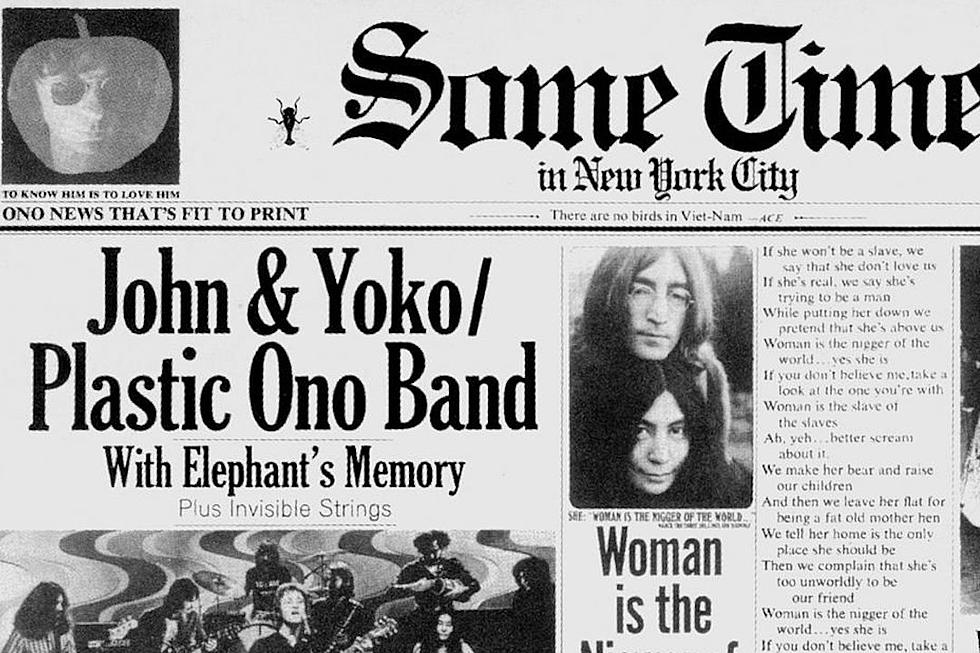

Lennon's biggest successes at quick-turnaround songwriting so far had been distinctly personal: the Beatles' "Ballad of John and Yoko" and the early solo song "Cold Turkey." Adapting that kind of top-of-his-head commentary to issues of the day might have resonated back then, but few people remember John Sinclair (the writer and MC5 band manager jailed for passing two joints to an undercover cop) and the Attica prison riots (sparked by demands for better living conditions) now. Both were big news in 1971, and the subjects of songs on Some Time in New York City – which, fittingly, used an instantly dated newspaper mock-up for its cover image – but are nothing more than Google fodder for the most committed fan today.

Without universal themes that could resonate across generations, Some Time in New York City tends to come off as empty proselytizing. The sentiments were too brittle, and often all edge — the result, no doubt, of their rushed creation. Even Lennon eventually came to see the folly of this kind of freeze-dried creativity. "I like to do inspirational work," he told David Sheff in 1980. "I'd never write a song like ['John Sinclair'] now."

Worse, many of the sentiments sound just like what they were: songs written for instant consumption. Sample lyric from "Angela," about a jailed Black Panther supporter: "They gave you coffee; they gave you tea / They gave you everything but equality." Meanwhile, "The Luck of the Irish" – one of two songs that supported Northern Ireland's Republican movement – included lazy (reportedly Yoko Ono-composed) cliches like shamrocks, leprechauns and the hope that the world would one day become "one big Blarney stone."

The muscular, often messy backing of Elephant's Memory, a local group Lennon had fallen in with, only underscores the drive-by nature of the content.

To some degree, Lennon seemed to be focusing outward in order to avoid the looming problems in his life. As he'd become a fixture in New York City's counterculture, issues with the U.S. government began to intensify. Lennon finally received a letter from the INS earlier in 1972 demanding that he leave the country in three weeks or face deportation. Grasping at straws, they cited a 1968 misdemeanor conviction for marijuana possession. Lennon lawyered up, but the fight continued unabated until President Nixon's entanglement in the Watergate scandal. Lennon finally received his green card in 1976.

"It was hassling me, because that was when I was hanging out with Elephant's Memory, and I wanted to rock – to go out on the road. But I couldn't do that because I always had to be in New York for something, and I was hassled," Lennon told Hit Parader in 1975. "I guess it showed in me work. But whatever happens to you happens in your work."

Listen to John Lennon's 'John Sinclair'

In truth, time had already rendered some of the songs irrelevant before the album even arrived. The paper-thin lyrics to "John Sinclair" ("Free John now," Lennon sang, "if we can") were dashed off for use during a political rally on Dec. 10, 1971, in Ann Arbor – and Sinclair was promptly released three days later. (Incidentally, the FBI's lengthy surveillance of Lennon began at this rally.) Angela Davis, subject of the similarly outdated "Angela," had also been acquitted by the summer of 1972.

Sometimes Lennon's sentiments simply made no sense. "Sunday Bloody Sunday," which took the side of the IRA against the British Army in the ongoing violent struggles in Ireland, served to muddy Lennon's longstanding stand on pacifism. "Attica State," written before a drunken birthday jam session in 1971, took his suddenly disorganized passions another step further: "Free all prisoners everywhere," Lennon sang. "All they want is truth and justice."

Critics savaged Some Time in New York City, and fans apparently agreed. The project barely cracked Billboard's Top 50, marking the worst post-Beatles showing for one of Lennon's original albums. Chastised, he quickly turned back toward the kind of conventional songwriting that made 1971's Imagine a double-platinum smash. Lennon would score three more Top 20 hits over the next couple of years, including the chart-topping "Whatever Gets You Through the Night," before retiring to focus on family.

"I'm pretty movable, as an artist, you know. ... It became journalism and not poetry – and I basically feel that I'm a poet," he told Rolling Stone in 1975. "Then I began to take it seriously on another level, saying, 'Well, I am reflecting what is going on, right?' And then I was making an effort to reflect what was going on. Well, it doesn't work like that. It doesn't work as pop music or what I want to do. It just doesn't make sense."

Still, like even the least of the Beatles' solo projects, Some Time in New York City wasn't without its small-scale charms. "New York City" served as a Chuck Berry-esque mash note to Lennon's new hometown, an effortless romp in an album sorely lacking such moments. A steel-stringed Dobro imbued "John Sinclair" with a delightful rootsiness. Driven along by a nasty slide, "Attica State" was one of Lennon's more purposeful rockers – never an easy thing to accomplish among producer Phil Spector's legendary clutter. "Woman is the N----- of the World," the latest in a string of sloganeering attempts that went back to "Give Peace a Chance," built to a dark and thunderous conclusion.

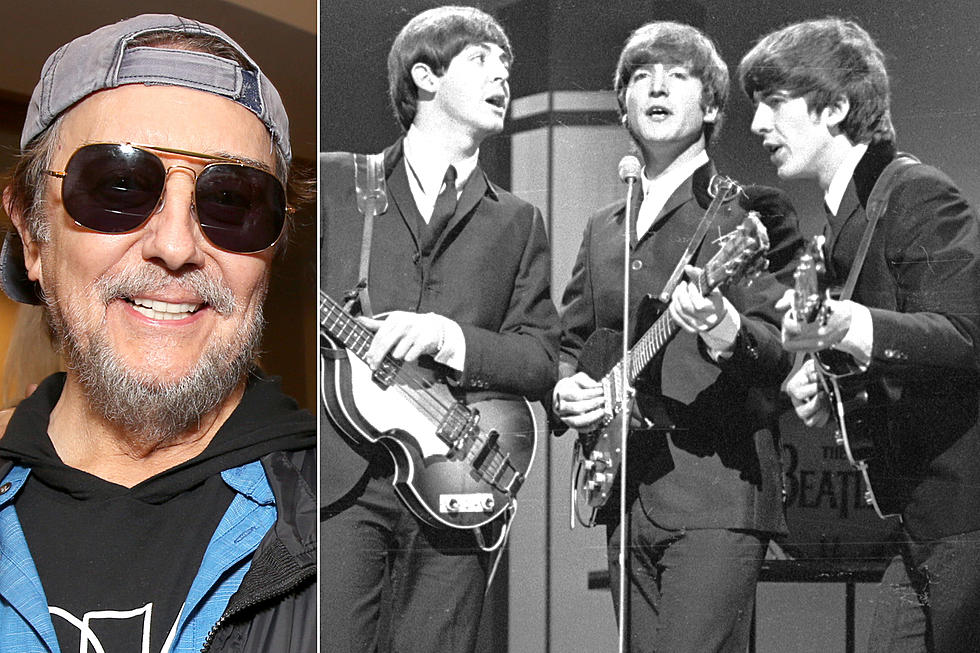

A second disc of live performances was hit and miss. The first side marked an important passage with songs from a 1969 performance featuring George Harrison, Eric Clapton and Billy Preston, while the second – from a 1971 encore with Frank Zappa – was occasionally brilliantly unhinged.

John Lennon Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock