Revisiting John Lennon’s Five-Year Battle With the FBI

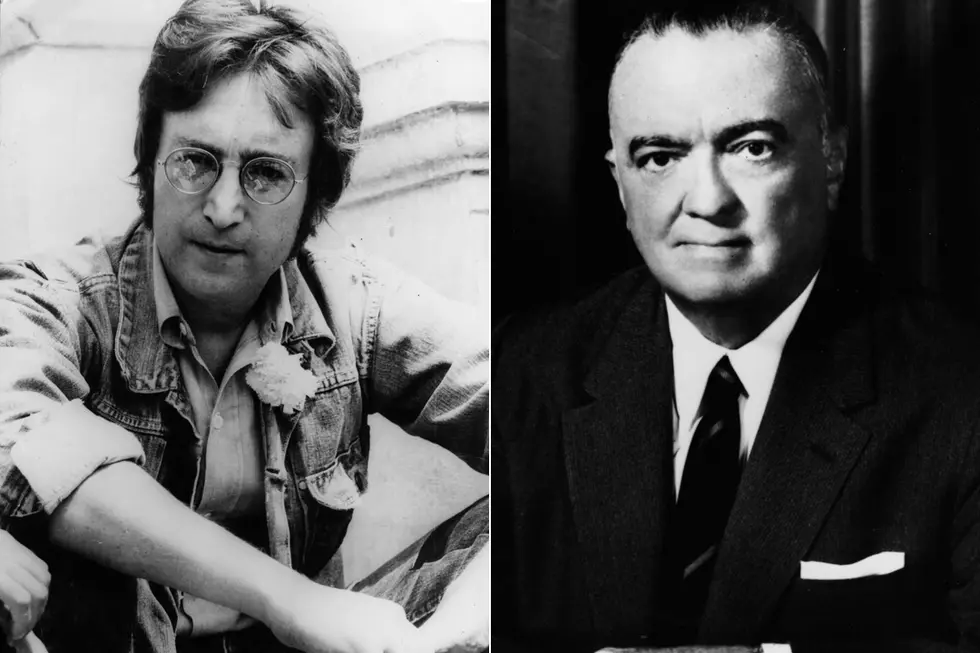

When John Lennon received his green card in July 1976, it was a hard-fought victory over the U.S. government. Several years earlier, he had been under surveillance from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the government had tried to deport him because of his political activism. Over the years, the FBI gathered nearly 300 pages of information on Lennon.

As the Vietnam War devolved into a quagmire, Lennon became more involved in the peace movement, which led to a friendship with radicals like Jerry Rubin and Bobby Seale. In December 1971, a few months after Lennon and Yoko Ono moved to New York, he sang at a rally for John Sinclair of the White Panthers, who was serving a 10-year sentence for selling two joints – the subject of Abbie Hoffman’s rant at Woodstock during the Who’s set. Sinclair was released within days, but unknown to Lennon, the FBI was in the audience taking notes. This was essentially the beginning of the government’s involvement into Lennon’s life.

Historian Jon Wiener spent 14 years trying to get the Bureau to release its files on Lennon under the Freedom of Information Act. His book, Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files, shows that President Richard Nixon was worried that Lennon could affect his chances at being re-elected.

“The '72 election was going to be the first in which 18-year olds had the right to vote,” Wiener told NPR in 2000. “Before that you had to be 21. Everybody knew that young people were the strongest anti-war constituency, so the question was, for Lennon, how could he use his power as a celebrity to get young people into the political process?”

The idea was a tour intended to mobilize the new youth vote against the administration. It would follow Nixon’s campaign stops across the country, concluding with a three-day festival in Miami, where the Republican National Convention would be taking place. But because the FBI was tapping Lennon’s phones and following him around, it never got past the discussion stage, and Lennon was soon forced into a different fight with the government.

Sen. Strom Thurmond (R-Ga.), who was on the Internal Security Subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee, wrote a letter to the White House in early February 1972 apprising them of Lennon’s plans. He proposed that the best way to stop Lennon would be to have his visa terminated.

The Immigration and Naturalization Service delivered a letter to the Lennons on March 1 requesting that they leave the country within two weeks or face deportation hearings. They had used Lennon’s 1968 conviction for marijuana possession – a misdemeanor – as the reason for the deportation.

As they fought the INS, Hoffman and Rubin continued their plans to demonstrate outside the convention. But Lennon had to bow out because it was too dangerous to their fight to stay in the country. On Aug. 30, 1972, a memo was sent to acting director L. Patrick Gray – Hoover died in May – that the FBI was ending its surveillance of Lennon. “All advised that during the month of July 1972, that the subject has fallen out of favor of activists Jerry Rubin, Stewart Albert and Rennie Davis, due to subject's lack of interest in committing himself to involvement in anti-war and new left activities. In view of this information, the New York division is placing this case in a pending inactive status.”

As Wiener pointed out, it was a victory for Nixon. “What this really is saying here is that the Immigration Service and the FBI have succeeded in pressuring Lennon to cancel his plans for this national concert tour and to withdraw from anti-war activity. His lawyers told him that his case for fighting deportation was a pretty weak one. In fact, they'd never seen anyone win a case under these terms, and therefore, the legal advice was [to not] do anything more that would further provoke the Nixon administration. He really wanted to stay in the United States. Yoko was involved, at that point, in a custody dispute over her daughter from a previous marriage -- her daughter Kyoko. So John, if he had been deported, Yoko would've stayed behind. He didn’t want to be separated from Yoko [Ono already had a green card], so he cancelled the plans for the concert tour. He dropped out of movement activity and the FBI is reporting that they have accomplished their job.”

But the fight didn’t end there. Even after Nixon had been re-elected by a landslide, Lennon continued to receive deportation notices from the INS, which would be appealed by Leon Wildes, Lennon’s lawyer. In their typically satirical way, Lennon and Ono held a press conference on April Fool’s Day 1973 announcing the formation of Nutopia, a “conceptual country” with “no land, no boundaries, no passports, only people.” Citizenship was granted by “declaration of your awareness to Nutopia,” and all citizens were granted ambassadorship. Therefore, they were entitled to diplomatic immunity.

While Lennon was being absurdist, Wildes got serious. He turned the tables on the government, suing Attorney General John Mitchell and other high-level officials for their conspiratorial attempts to throw Lennon out of the country. Their investigation turned up documents from Hoover to H. R. Haldeman, Nixon’s Chief of Staff informing him of the FBI’s progress. This ultimately proved that Nixon’s political motives were the reason for the deportation attempts, rather than the belief that Lennon was a threat to the American way of life.

As this was going on, Nixon became embroiled in the Watergate scandal. His resignation in August 1974 effectively ended the fight against Lennon. In October 1975, the New York State Supreme Court overturned the deportation order. “The courts will not condone selective deportation based upon secret political grounds.” Judge Irving Kaufman said. “Lennon’s four-year battle to remain in our country is testimony to his faith in this American dream.” The victory coincided with the birth of John and Yoko’s son Sean.

Eight months later, the green card arrived. On the steps of the courthouse, Lennon held an impromptu press conference to “thank all the kids and the fans who wrote to all their senators, and their petitions and all the rest […] who were working behind the scenes for five years with no pay.”

Lennon remained a resident the U.S. until his killing on Dec. 8, 1980 in front of the Dakota, his apartment building in New York.

See John Lennon and Other Rockers in the Top 100 Albums of the '70s

You Think You Know the Beatles?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock