Graham Nash Reflects on His Photos of CSNY, Dylan, Joni Mitchell

"I want to be invisible," says Graham Nash.

But the singer-songwriter isn't dreaming of a comic book superpower. Instead he's thinking about his approach to photography — a passion he's held for most of his 79 years.

"I can feel a camera coming from 100 yards away," he tells UCR. "You want to look your best; you put on that face. I’ve had millions of pictures taken of me, and I don’t like that face that I present. I’m trying to look like Elvis [Presley]; I’m trying to be as cool as James Dean. [Laughs.] Many of the images [I've taken] look like nobody knew I was there taking their picture — and, in fact, many are."

His upcoming book, A Life in Focus: The Photography of Graham Nash (out Nov. 30 via Insight Editions), collects many of these images — often moody, occasionally playful shots featuring such famous subjects as Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash and onetime bandmates David Crosby, Stephen Stills and Neil Young. The book spans Nash's life and career through the literal lens of photography: developing his obsession around age 10, honing his skills through the artistic explosion of the Laurel Canyon scene, still waiting today for that next interesting shot to appear.

Nash spoke to UCR about many of the book's most striking images. Along the way, he also surveyed his latest musical projects — including multiple in-progress albums.

Between this new book, the Deja Vu reissue and some upcoming tour dates, you've been pretty busy. Am I missing anything? What about new music?

A couple years ago, I got a band together and did [1971's] Songs for Beginners from start to finish, then took an intermission and came back and did [1974's] Wild Tales start to finish. We recorded the four shows where we did those albums, and it’s coming out as a double live album in early 2022. I’ve been recording remotely, which is really interesting — sending my acoustic guitar and rough vocal to my guitar player, Shane Fontayne, in Los Angeles; he puts guitar and bass on them, and then he sends it to my keyboard player, Todd Caldwell, who would put keyboards on. He would send it to his brother, who is a drummer, in Lubbock, Texas; he’d put the drums on and send it back to me, and I’d mix it. It’s been very interesting — we’ve done seven tracks that way.

For some people, file-swapping eases some of the pressure of recording. For others, it's a nuisance and you lose that band vibe. What's it been like for you?

When I first started making records way back in the early ‘60s, it was two-track. And now you’ve got 1,000 on your phone. So I love new technology — and the secret, as far as I’m concerned, in terms of remotely making records, is you need to make sure it feels like the four guys are in the same room.

That’s the challenge, right?

It’s a challenge, but I’m facing that challenge and overcoming that challenge. These tracks sound fabulous. I’m also eight tracks into an album with [former Hollies bandmate] Allan Clarke. I’ve been a friend of Allan’s since we were six years old. We started the Hollies together in December of 1962, and we’ve never made an record just the two of us. People are gonna be shocked at how well Allan is singing — don’t forget, he left the Hollies because he was having trouble with his throat and couldn’t hit those high notes anymore. For 20 years, he didn’t sing. And then to work on this project and hear him singing so well and writing songs so well, I’m very happy with it so far.

Let's talk about the book. That photo of Mama Cass Elliot, "Cass Elliot," just radiates joy. It reminds me of what you say in the book: It’s the photographer’s job to capture these random moments before they disappear.

That’s Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “Decisive Moment,” when you press the trigger on the camera. You have to really be courageous.

What was the context of that photo?

[Elliot] was on the phone to Crosby, as a matter of fact. The three of us have always maintained that Cass Elliot knew what we were going to sound like before we’d sung together. She knew that I was unhappy with the Hollies; she knew that David had been thrown out of the Byrds and that Buffalo Springfield had broken up. She knew that David and Stephen were trying to do an Everly Brothers two-part thing. And then I come along. And when we first sang together, we had to stop after about 45 seconds because — those three bands were pretty good harmony bands, but this was completely different, and it shocked us at how instantly [we created] a completely different audio blend. It happened in 45 seconds! We didn’t have to work for four months to try and sing a song.

I guess it’s that mystery: Why do those voices fit together so well?

Yes. We’ve always tried to make our three voices sound like one voice.

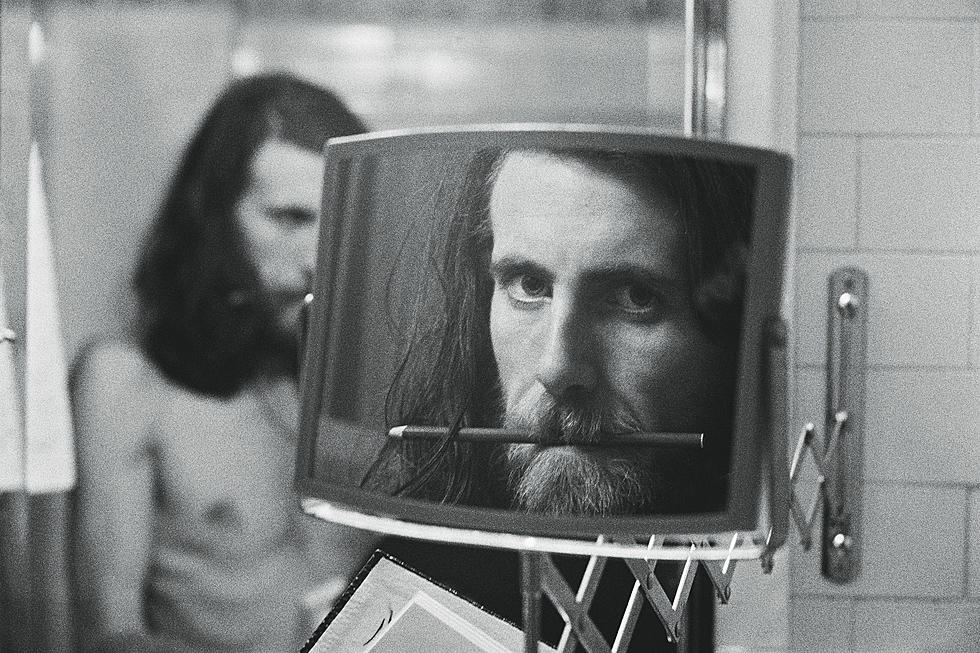

I also absolutely love the series of photos titled "Neil Young Rehearsing for Deja Vu," particularly number three, which shows him looking at the camera, almost surprised, like he just turned around and you were there.

That’s exactly what happened!

It has this beautiful almost chiaroscuro effect, too. What’s your memory of capturing that?

It’s more difficult shooting pictures of Neil than it is David or Stephen. Because David and Stephen are my friends. Neil is my friend, obviously — I’ve been making music with him for about 50 years. But he’s less approachable than David or Stephen. He’s in his own world, and I love the fact that he’s completely dedicated to the muse of music. And if it feels right, like I say in the book, he’s right there. When it’s not right, "Where’s Neil?" What I didn’t know when we were rehearsing Deja Vu in Studio City [Calif.], when I took those pictures, is that Neil would leave that rehearsal and go to the studio and start making After the Gold Rush. Fantastic! Are you kidding? What a musician. [All those photos]l happened within five minutes. I felt that Neil knew that I’d taken interesting shots of him, and he was hemming and hawing, so I stopped taking pictures, but I’d already shot four or five that I knew would be alright.

Did the other guys ever get annoyed with you taking their pictures so often?

Me and David and Stephen would hang out all day every day for a long time, so I was always taking pictures of them — so what? They knew I would take pictures of them, so they never gave me any edge or negative feeling at all.

I love everything about the "CSNY in Maui" photo — everyone has such a unique expression that you can create your own backstory. My favorite part is the concerned look on your face — it almost seems like you, as the photographer, were mildly distracted by hoping the photo turned out.

I was a little worried that what I’d set up would work. In fact, you can see from reading the book that there’s only one shot. It’s not like there were 10 shots and we chose the best or we put this face on that body. No, there’s one shot! That’s it. You never know, of course [if the photo will turn out].

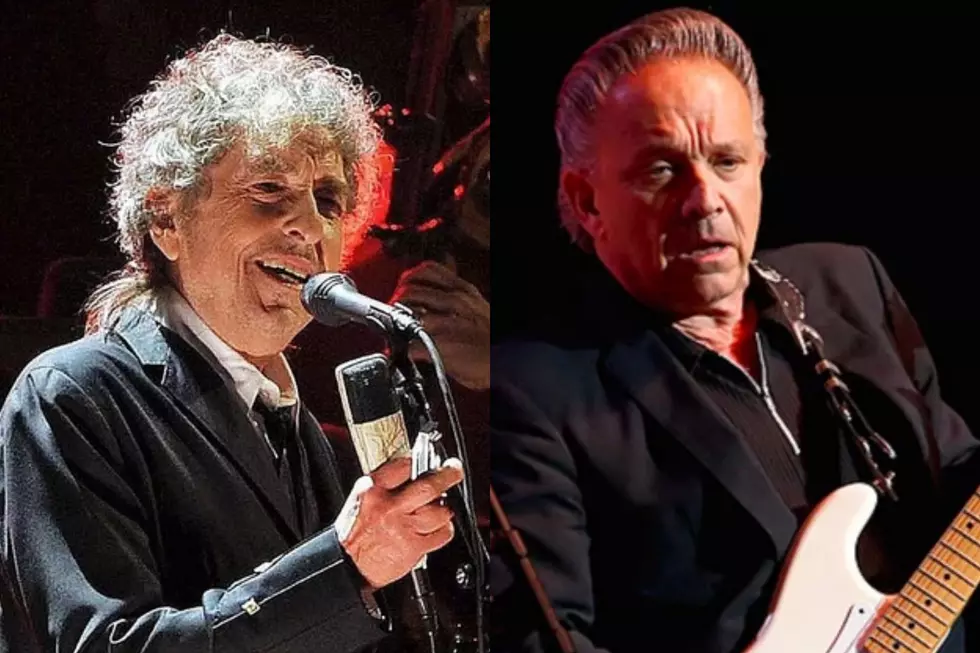

That concert photo of Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash with the damaged negative, "Bob & Johnny II," is intriguing. Something about the damage adds to the beauty — it’s like time trying to fade a memory.

That’s exactly why I showed it — under normal circumstances, you wouldn’t show a damaged negative. But in this case the damage to the negative added to the mystery of the moment, I believe. And those two guys really liked each other. It’s Bob Dylan, for fuck’s sake! To me, the greatest writer and singer of songs that we have in this country. To see his appreciation of Johnny Cash — they really liked each other. I’ve seen a couple of letters between them that are incredibly, beautifully friendly. It wasn’t like “That’s Bob Dylan, and that’s Johnny Cash.” No. They were in the same business, the same line of work. They loved each other. It was fun to see that. And don’t forget — in 1969, we had only just finished the first CSN record. I was just this man who came [to the show] with Joni [Mitchell]. Nobody knew I was a musician. Nobody knew!

There are so many haunting photos of Joni Mitchell in the book, including my favorite, "Joni Listening to Music," in which you captured her through a hole in a chair. It’s one of many images that have a voyeuristic quality to them.

And Joni is such a beautiful woman, obviously. I was totally in love. We used to light up the room when we walked in — all those great things about a blooming romance. And Joni is also an incredible — let’s say "genius" at music and painting. But I like to be invisible, and I’ve taken some of my best shots like that.

You write in the introduction about being bale to “see” music and describing sounds with colors. Do you have synesthesia?

I don’t have synesthesia. I know very much about it, particularly as it applies to artists like [Wassily] Kandinsky. Mine is a slightly different form of that — for instance, and I talk about this in the book, but with Ansel Adams’ famous “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico” image taken in 1941. When I look at the dark areas in the foreground, I can certainly imagine cellos playing. If I look up and see the grey, wispy clouds, I can hear violas playing — not a particular melody, but I can feel them playing. In my mind, music and photography are very connected.

Top 100 '70s Rock Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock