When Elvis Costello Looked Inward on ‘Imperial Bedroom’

Elvis Costello once described Imperial Bedroom as his "most optimistic album to date."

His seventh studio album and sixth with the Attractions went on to touch topics like cheating spouses ("there's no money-back guarantee on future happiness"), relationships disintegrating into violence ("I can't believe what we've forgotten / and I even slapped your face and made you cry") and general self-condemnation ("Love is always scampering or cowering or fawning / You drink yourself insensitive and hate yourself in the morning").

So, Costello's definition of "optimistic" might be different from the average person's. Imperial Bedroom wasn't exactly a happy-go-lucky LP, but it was one of Costello's most mature attempts at wrestling with one's existentialism.

Costello's music had often been described as cynical and vindictive from the moment he released his debut album, 1977's My Aim Is True. His infamous comment to NME back then stating that the only two emotions he knew about and felt were "revenge and guilt" certainly didn't help his reputation.

This "self-perpetuated venom," as Costello described it to Rolling Stone in 1982, was threatening to engulf his career. Little room was left for Costello to prove that he wasn't actually as insensitive or uncaring as some might have been led to believe based on his lyrics and quotes to the media.

Then Costello sparked a drunken brawl in 1979 at Columbus, Ohio after spouting racial epithets about Black musicians, namely James Brown and Ray Charles. Costello attempted to clear things up at an uncomfortable press conference that followed in New York, but lingering issues remained.

Listen to Elvis Costello's 'Man Out of Time'

Michael Jackson was also recording with Paul McCartney at AIR Recording Studios in London, as the Imperial Bedroom sessions continued. Bassist Bruce Thomas ran into Jackson while vocals were being recorded in another room, and the mood instantly shifted when he was introduced as Costello's bandmate.

"Suddenly, there was a freeze out. Michael Jackson was, 'Oh, God, I don't dig that guy. ... I don't dig that guy,'" Costello told Rolling Stone. "He had heard about it third hand, from Quincy Jones – two guys I have a tremendous amount of admiration for. It depressed me that I wouldn't be able to go up to him. I wouldn't be able to go up and shake his hand, because he wouldn't want to shake my hand.

"I'm not saying I wasn't responsible for my actions; that sounds like I'm trying to excuse myself," Costello added. "But I was not very responsible. There's a distinct difference. I was completely irresponsible, in fact. And far from carefree — careless with everything. With everything that I really care about."

Costello was now two years away from turning 30, so older and presumably wiser. In keeping, he took 12 weeks to complete Imperial Bedroom, stretching out the process in a way he hadn't before. He also recorded again without Nick Lowe, a trusted collaborator who'd produced Costello's first five albums before the immediately preceding covers-focused Almost Blue.

"We had all heard each other's jokes at least once by this point," Costello wrote in the liner notes for 1994 reissue of Imperial Bedroom. "In any case, I knew that I wanted to try a few things in the studio that I suspected would quickly exhaust Nick's patience."

Instead he chose producer Geoff Emerick, notable for engineering work with the Beatles. Emerick's influence was palpable throughout Imperial Bedroom, from the unexpected ending on "Man Out of Time" to the exuberant arrangement of "... And in Every Home." Emerick was officially credited with producing the LP "from an original idea by Elvis Costello," an attempt to ensure Emerick got the credit he deserved.

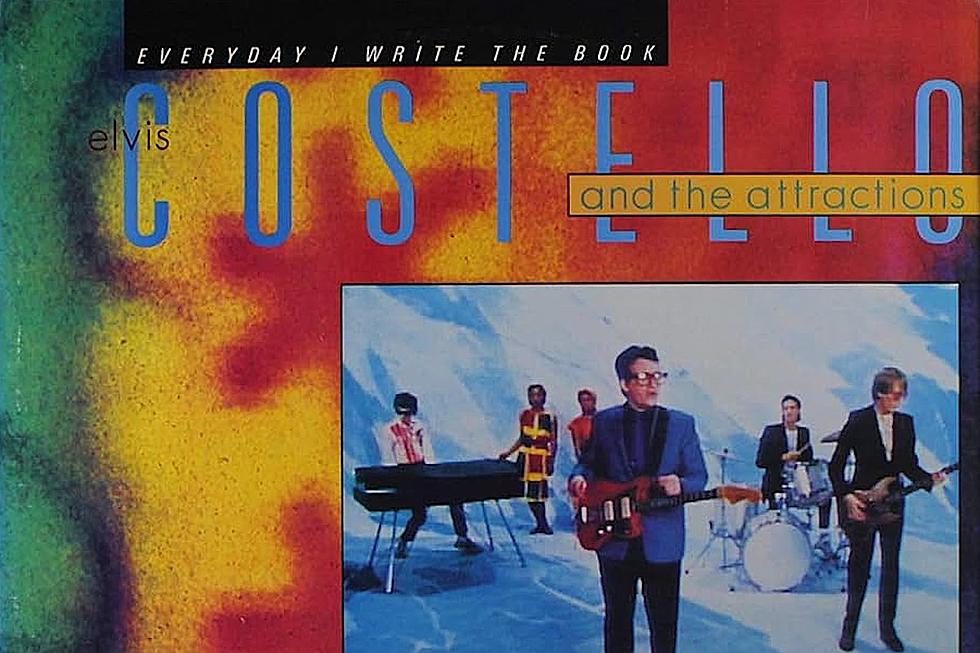

Watch the Music Video for Elvis Costello's 'You Little Fool'

"This was not the conceit it may have appeared to be at the time," Costello later wrote. He'd co-produced East Side Story for Squeeze in 1981, and saw first hand how recognition could be easily misplaced. "In a very short time," Costello said, the entirety of the production became "attributed to myself alone, with co-producer Roger Bechirian's name often omitted from reviews and articles.

"I did not want this process to be repeated," he added, "so although I was nominally co-producer with Geoff, in truth he did nearly everything that could be called 'production' in terms of sound, while I concentrated on the music." (Squeeze's Chris Difford was also credited as a lyricist for one of Imperial Bedroom's tracks, "Boy With a Problem.")

Keeping things organized behind the production console didn't necessarily mean applying strict rules to whatever arose from these sessions, which borrowed from bright, '60s pop sounds but didn't directly copy them. "We did not make any attempt to have the songs obey an arrangement or production style," Costello wrote, "rather we tried to make the most out of this musical variety."

Part of that meant experimenting with instruments and their typical sounds. Imperial Bedroom arrived on July 2, 1982 with a 12-string Martin guitar was "bugged" and run through a Hammond Leslie speaker on "Shabby Doll," a National Steel Dobro mimicked a sitar in "Pidgin English" and, using another Beatles-esque method, a harpsichord part in "You Little Fool" was redubbed using the backward-tape technique.

"You Little Fool" was subsequently released as the first single from Imperial Bedroom, over Costello's objections. He felt "Man Out of Time" was the "heart" of the LP, while "You Little Fool" – a song Costello said in his autobiography was about "a teenage girl surrendering to an unworthy, older man" – wasn't representative of the album as a whole.

Still, a radio-friendly hook was enough to prompt his record label to release "You Little Fool" anyway.

Listen to Elvis Costello's 'The Loved Ones'

Elsewhere, Costello continued to combine forbidding, even ill-tempered lyrics with light, amiable pop. That's perhaps best illustrated on "The Loved Ones" a song Costello described as the "hardest song to get over" in the interview with Rolling Stone.

"Considering it’s got such a light pop tune, it’s like saying, 'Fuck posterity; it’s better to live.' It’s the opposite of [Neil Young's] Rust Never Sleeps," Costello added. "It’s about, fuck being a junkie and dying in some phony romantic way like Brendan Behan or Dylan Thomas. Somebody in your family’s got to bury you, you know? That’s a complicated idea to put in a pop song. I didn’t want to write a story around it, I wanted to just throw all of those ideas into a song – around a good pop hook."

In some ways, Costello turned over new leaf with Imperial Bedroom; in others, he was only just beginning to self-reflect after five years of making records. "A lot of songs are about the sort of disgust with your own self," he later told Performing Songwriter. "There were a lot of things that I wasn’t very happy with during that time. I wanted songs to blow up the world. I had mad ambitions – not mad as in 'ambition to be famous.' I never wanted that; that just came as an accident of it all. But somehow you look at yourself and you're not happy with what you see."

Many of Costello's frustrations, as he admitted to the New York Times in 1982, were aimed at himself. "The more personal songs are either imaginary scenarios, observations of other people, or observations of myself," he said. "Most of the really vitriolic songs I've written have been observations of myself."

Imperial Bedroom earned widespread praise, reaching No. 6 in the U.K. charts and the Top 40 in the U.S. The LP also convinced Costello to refocus on the here and now.

"The important things to me are the melody, the words, the way you sing them, all the little innuendos you can get into them – and above all, the feeling behind them," he added. "But I hate this precious idea that every song has to be the Sermon on the Mount. The songs I write for my next album will be about whatever happens to me between now and when we start recording again – and that's what it's about, really. It's about life."

Top 40 New Wave Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock