How Eagles Resisted Hollywood Bid for ‘Hotel California’ Movie

One reason Eagles became so successful was that their lyrics perfectly complemented their music, adding depth of feeling to those timeless melodies. In creating those lyrics, the band added a powerful visual element to its output, so it's hardly surprising that the idea of making a movie out of their stories entered the heads of Hollywood producers.

One such person was Julia Phillips, the first female producer to win an Oscar. In 1977, she was at the top of her game, having been behind the hit movies The Sting and Taxi Driver; her latest project, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, was beginning to raise rumors backstage.

As Phillips – who died in 2002 – noted in her 1991 memoir, You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again, her ambition was to create “the true marriage of art and commerce” with her story The Third Man Through the Door. She became convinced that the Eagles’ latest album, Hotel California, provided the musical force she needed. “I’ve always wanted to do a movie where the music was integral,” she recalled thinking. “Incorporate the musical talent with the writing talent at the very beginning.”

She thought Third Man was “about a lot of the stuff these guys are writing about,” but she believed she had a strong commercial argument, too. She had noticed the words “copyright in dispute” on the back of the album sleeve and discovered the unusual conditions of its release: While there was indeed an argument over ownership of the songs, Eagles were “getting so fucking hot, nobody want[ed] to blow the money” by holding off on the release. Because the LP was available through a branch of Warner Bros., and the same corporation was funding her movie, Phillips reflected, “It would be interesting … to see if these guys are interested in going into partnership on TMTTD and settling their lawsuit.”

That was the argument that persuaded Eagles manager Irving Azoff to hold a preliminary meeting with her. She said he told her: “I don’t have the vaguest idea what you have in mind, but you seem like a crazy creative person. Let me put this together.”

What Azoff didn’t know was that Phillips’ cocaine habit was running out of control, and her penchant for the powder-powered high would soon bring her career high to an end.

Part and parcel of that end was a follow-up meeting she held at her Beverly Hills home with Azoff, Glenn Frey and Don Henley. In an attempt to put everyone at ease, she said, she brought out a large amount of coke and offered it around. “Everyone but Irving partakes throughout,” she remembered. “I do my riff. … Don Henley seems bright and responsive. I get kind of hung up on his ears, though, which stick out. A recalcitrant Glenn Frey does a lot of blow and seems angry about it. … They seem sparked by the idea, but by then everyone except Irving is pretty lit by the blow. They agree to think about it.”

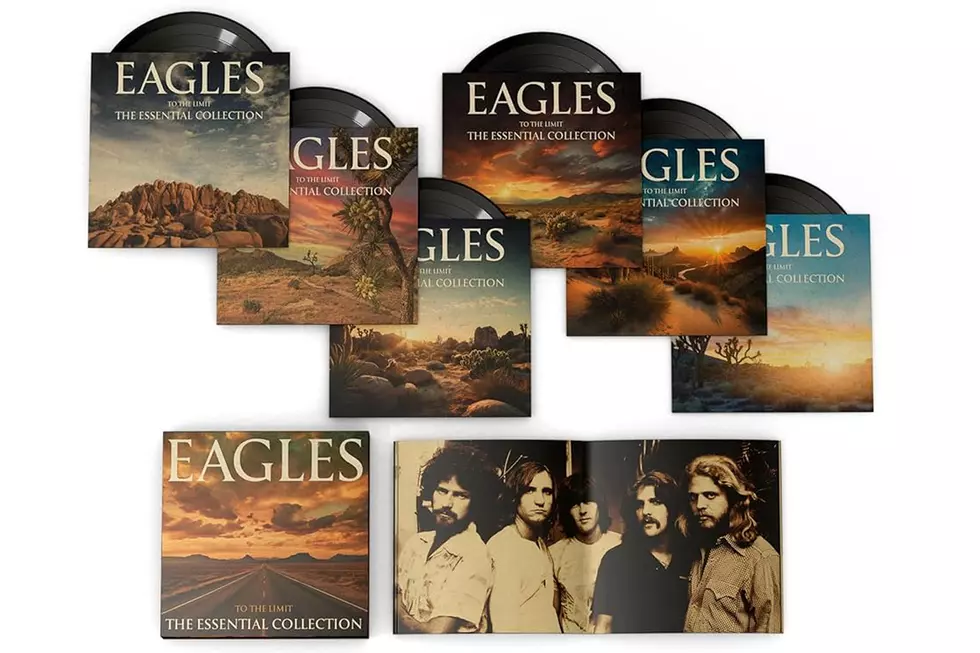

But that’s not how Henley remembered the incident. In the 2004 book To the Limit: The Untold Story of the Eagles by Marc Eliot, it's suggested that Phillips found the band members “scruffy and sullen, acting, in her opinion, amateurishly arrogant, as if they were determined to prove that what everyone in film thought about rock stars was true. … [They] talked of protecting their ‘purity,’ even as, according to Phillips, they snorted an ounce of coke off the table.”

“She’s a liar,” Henley responded. “Both Glenn and I remember that day quite vividly. We had gone to her house reluctantly. We’d already had some bad experiences with movie people. … They always thought we should be excited or flattered because they wanted to make movies out of our songs. In fact, we really didn’t want anything to do with it. We were pretty sure they’d take our songs and ruin them. We knew enough about the film business to know you’d have to relinquish all control and that it’s somebody else’s vision, just like rock videos are today.”

Henley said coke was “at the peak of its popularity in Hollywood, and Phillips was in the process of flaming out her career on it. ... We sat there, polite but not terribly friendly. We were too wary to be friendly. In an effort to loosen us up … she dragged out this huge ashtray filled with a mound of coke. … She offered us some, and we said no; we didn’t know her that well, and it was a business meeting.”

Partly as a result of the meeting, Eliot reported, Frey decided to leave Hollywood for Colorado to “cool out,” and Henley was soon “felled by another episode of stomach problems.” Azoff advised Phillips that any further discussions would have to be postponed indefinitely.

Phillips suspected her time at the top was nearing its end. She admitted that, when she met her Third Man financiers to update them, “my third eye does not see: This is it, babe. Your last lunch in this town. ... I have to tell them that the Eagles have fallen out. Henley is in a hospital with an ulcer attack, and Frey has gone to Colorado to build a house. I wonder if they’re breaking up.” She added that they tried to act like it didn’t matter, but they all knew it did.

Soon afterward, Phillips was fired by her Close Encounters colleagues after having realized that most of her friends had become adversaries. “Funny how that happens when a lot of money is on the table and the stakes are getting higher all the time,” she reflected, accepting that her once-close relationship with director Steven Spielberg had disintegrated and she wound up living with her drug dealer to “cut out the middleman.”

In her bid to have art imitate life, Phillips managed to help life imitate art, a friend of the Eagles told Eliot. He said the band was never likely to have been persuaded to approve the movie plan; Henley in particular was “afraid of seeing what he considered his finest, most personal work reduced to the level of a sitcom.” “They really didn’t want to see Hotel California made into a movie," the source noted. "They were suspicious of the film business. After all, that was what Hotel California was all about.”

Eagles Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock