Deep Purple’s Ian Paice Says There’s ‘No Logic to Anything That Goes on in Our Business': Exclusive Interview

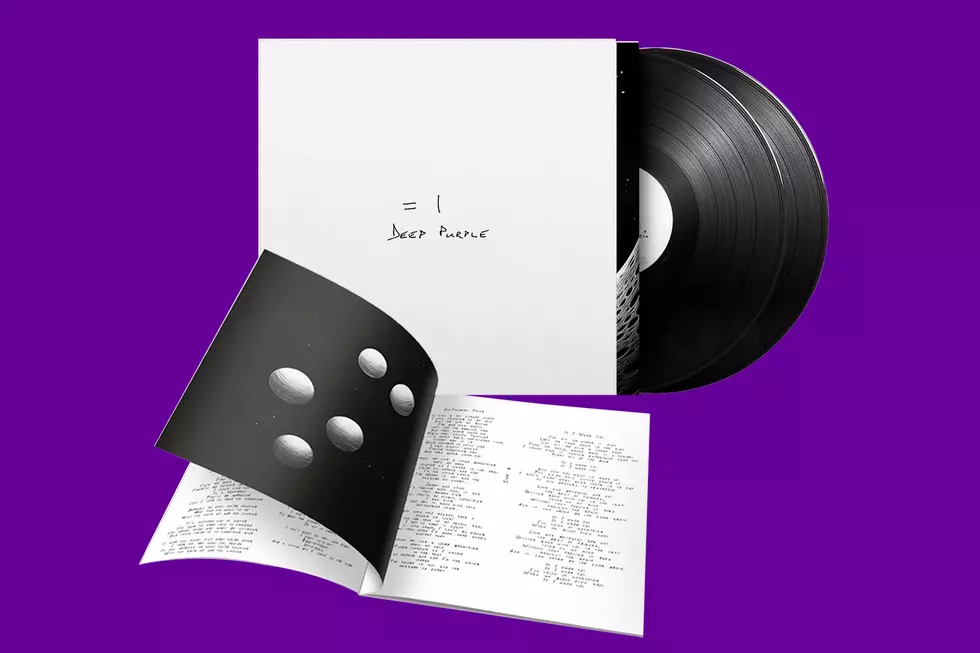

If their new tour proves to be Deep Purple’s final go-around, something which they’ve hinted at recently, they’re certainly going out with a bang. Creeping toward the half-century mark as a band, the legendary classic rockers just released inFinite, an album that finds the group continuing to build on the positive momentum generated by 2013’s Now What?!, which featured Bob Ezrin (Kiss, Pink Floyd) behind the boards as producer.

The collaboration was so effective that Ezrin is once again working with the band for the new album, and from the opening moments of “Time for Bedlam,” the LP's lead cut, it’s clear the group hasn’t lost an ounce of swagger and energy. They’ll be back out on the road in the U.S. later this summer, sharing the stage with Alice Cooper for a series of shows billed as The Long Goodbye. So is this the end? We went to drummer Ian Paice to get the answer to that question and many others.

It’s great to finally have this new Deep Purple album in hand. The album title looks like Infinite at first glance, but there’s also an important accent placed on the "finite” part of the album title. What’s the proper way to pronounce it?

Well, it’s of those wonderful ambiguous sort of words the way it’s done, isn’t it? The music is infinite. Once it’s recorded, it’s there forever. It’s immortal. Unfortunately, musicians are not. [Laughs] We have to acknowledge that that day, when we have to call this wonderful day over, is approaching quickly. Emotionally, that’s a very, very hard thing to have to say. I’ve been involved with it 50 years next year. It’s very, very hard to turn around and say categorically, "This is the end, it will finish now. Goodbye." That’s really tough. We’ve left ourselves a little bit of wiggle room with the way we’ve done it and the naming of the next tour, which is The Long Goodbye tour. I’m not going to name names and I’m not going to cast aspersions, but there are lots of bands who have said, “This is the last tour, and when it’s over, it’s over,” and then a year later, they all get bored and they go back out on the road again. We’d rather not do it that way. If we announce it was the last, it is the last. But at the end of this, no matter how long it takes ... if it takes 12 months, okay, if it takes 24 months, that’s better, but I think just the freedom to come back and say, Look, after a year, let’s go back and make another record or let’s do three or four weeks a year [of shows]. Let’s just have fun with it. But to make that absolute cut-off decision of finality, I think that’s a pretty scary thing to do, and I don’t think you have to do it. But I don’t think you need to lie about it either.

It must be pretty staggering for you, as the guy who has been a part of all of it, to look at the fact that this band is going to mark 50 years next year. That must be quite something to comprehend.

Back in the day when you started, bands, if they were lucky, existed for five years. That was a major success. If you got through the decade, that was beyond comprehension. You know, with the passage of time, there are always going to be a few bands that hung around long enough to get to these positions. The [Rolling] Stones are the notable example -- sure, they take some time off, but they’re still there and they decide to do the gigs they want to do when they want to do them. We’ve had natural attrition through natural causes, losing people, so some of those bands that were magnificent in the day are not there anymore, because people are not on the planet anymore. It’s sort of like a natural selection. And a few bands will inevitably stay the course. It’s amazing that we were one of them.

It’s a good place to be. I think that with these past couple of records that you guys have done, you really have made two of the strongest records in your overall catalog.

We never felt that it was a risk. We know how good the musicianship in the band is and we know how good the adventure still is. More importantly, we know how much we all enjoy it, and that’s the secret. If you still enjoy what you do and you can focus all of those positive feelings into playing and creating new stuff, then there’s no reason why you shouldn’t come out with good product. But we never doubted it. You can make the best record at the wrong time and it will disappear without a trace. You can make the worst record at the right time and have a major hit. There’s no logic to anything that goes on in our business. All we’ve ever tried to do is capture the moment in the studio that was us at that time. Sometimes it’s been right, sometimes it’s been wrong. But we’ve always tried to capture the essence of a live band and I think if any of the records do stand the test of time, it’s just because of that fact. I think what we did with Now What?! Is just a reestablishing of the musical credentials of the band, never mind the fact that it was a big record in lots and lots of countries.

So it was a natural progression that following on from that, we had so much fun making that record with Bob Ezrin in Nashville, as soon as we got the chance to do another one, we’ll take all of that experience of working with him and the knowledge of the studio and enjoying it, to make another record. When you make records quickly, and you make them with a great deal of joy and pleasure, they generally turn out to be really good records. It’s when you have the opposite going on, where it takes a long time, nobody’s really enjoying it and it becomes a labor of work, rather than a labor of love. You end up with a record that maybe isn’t going to do so much.

Has Bob Ezrin been an important factor on influencing the band to work faster and more efficiently as a band in the studio?

Definitely to work more efficiently, yeah. He doesn’t waste time. He’s in the control room, hearing the whole picture. Although we’re hearing everybody else in the studio, we’re really concentrating on our own little world. I’m going, “The drums have got to be right, the drums have got to be right.” That’s me. What the other guys do, I can’t influence. So he’s listening to the whole thing, and once he knows it is there, he just tells us to stop. Because musicians will go on and on and on, thinking there’s a better take in them and sometimes there just isn’t. You can get to absolute perfection, but at that point, you can go into absolute sterility too. You’ve missed that moment where the music is good and the feeling of humanity is there, and that’s the important thing that Bob does. He goes, “Okay, we’ve got it.” We move on. The great thing of having a producer like Bob is that it is a wonderful two way trust. He trusts us to get the music created and played, and we trust him to make the decisions about when we move onto something else, and when we’ve captured the best we’re going to get.

Watch Deep Purple Talk About 'The Surprising'

It’s a really atmospheric album. The sound of the songs on this record really draw you in, stuff like “The Surprising,” for example. As a good album does, it takes you on a bit of a journey.

We decided after the pleasure of making Now What?!, where we did sort of kick down a lot of the self-imposed barriers and rules, we’d allowed to get around ourselves, we did throw a lot of them away with Bob’s pushing. Whatever little obstacles were still there, we got rid of them. If we get an idea and we like it, let’s work it through, let’s see if it will become a song. It doesn’t matter if they’re coming out of left field. If we feel it works well and it’s got some artistic merit and we can play it right and it’s got a charm of its own, then we’ll go for it. All the gloves are off, so any decent idea was followed through to its logical conclusion. There were really, really good ideas that didn’t make it. Not because they were bad ideas, they just didn’t live up to all of their little brothers and sisters that were better.

Do you guys hang onto any of that stuff?

Oh, yeah. Just because it didn’t work this time, doesn’t mean that if we decide to go into the studio and make another record in two or three years, that some of those other ideas won’t turn up again, albeit in a different form or with a different mindset. They’ll still be good ideas. The fact that we couldn’t get them together in time for this record, they will still be good ideas -- we just didn’t find the completeness or they just weren’t quite ready to be made.

“Time for Bedlam” is a great way to launch the album. It’s got almost a science-fiction feeling to it, starting with the way the vocals sound. I heard a little bit of that on “Birds of Prey” as well. What do you think was informing the material and the sound of this record?

When it comes to the lyrics of the album, I have to take a backseat here, because they really do come down to Roger [Glover]. Just looking at it from the outside, in four years since the last record, the world has become a much harder place. There are lots of horrible things going on and whatever you do reflects the world that you live in, you know? We’re not writing pretty little love songs here. We’re creating rock 'n' roll music which reflects who we are and what we’re experiencing at the time. Because of that, I think that it’s quite logical that the record is harder and some of the songs are darker and have in two or three of them, some serious meaning. We have crazy people in the world who are trying to f--- everything up again. Whereas 10 years ago, they were just sort of on the fringes. It was all under control. It’s not under control anymore.

Watch Deep Purple Talk About 'Roadhouse Blues'

How did you guys end up doing “Roadhouse Blues” on this record?

When we did the last record, for a bit of fun, we said, “Let’s do a track that was part of our childhood.” It could have been any of those great ‘50s rock and rollers. It could have been Little Richard, it could have been Chuck Berry, it could have been [Elvis] Presley. It happened to be a Jerry Lee Lewis song. We did “It’ll Be Me,” one of his great hits. And for us, this is part of where we came from musically. That period of great rock 'n' roll adventure, it’s part of what shaped us. I said, “It was so much fun doing somebody else’s music, why don’t we do it again on this album?” It’s not like it’s something new. You can go back to the first two or three Purple records, before Ian Gillan and Roger Glover -- we copied everybody’s records, because we couldn’t write our own music. I’d been playing between Deep Purple tours, because sometimes it would be a long time, I occasionally guest with a little tribute band and have some fun and actually get onstage and play drums in front of people, which is so very important for a live musician. If you work for a living on stage, you’d better keep playing onstage to keep your chops up. So I do this occasionally and we’d been playing some little club somewhere and it was towards the end of the show and we’d been playing “Black Night.” The music went down in volume and the singer just crept towards the microphone again and he went into “Roadhouse Blues.” It has the same tempo, the same feel, so it’s easily done.

But I just noticed the looks on people's’ faces. All of the guys in the band were smiling. I looked in the audience and their heads were going up and down and they had these great s--- eating grins on their faces. It’s a song that they knew and a song that they loved. They could see the musicians were enjoying it too. So when this came up, I suggested and said, “I’ve tried this onstage. This is really a great, cool fun song. Let’s take 20 minutes and see what we come up with. If we like it, we can keep it, if we don’t, we’ve lost 20 minutes.” When I put the idea forward, Bob Ezrin just said, “That’s it, I love that song!” He walked straight back into the control room, waiting for us to get it sorted out. We took about 10 minutes to arrange it, and I think about 15 minutes to record it. As we were playing it, everybody had the stupid s--- eating grin faces, really enjoying it. So we said, “Well, it may not be ours, but it’s such a good rock and roll tune. We’ve got to put it in.”

I know that you guys tracked a lot of the last record live. Did you keep that approach for this one too?

Every time. And I can prove it, because I have video of everything. I have cameras in the studio, because I love these moments, and some of them, you have to look back at them. There’s an interaction between musicians when you’re doing that. There may be nanoseconds of feel, when one guy does something and the others move with it. If you’re layering stuff, one guy at a time, you’ll end up with perfection, but you don’t get those moments. You don’t get that moment where I heard the bass player push a little bit further and I go with him. That’s what the feel is about, so we always, always go for the backing track with the four of us playing together. It’s the only way that we can get the feel of being on stage, which is what we’re trying to do. We’re not trying to make Sgt. Pepper. We’re not trying to make Pet Sounds. We’re trying to make a live capture of a great rock 'n' roll band. If you’re going to do that, you’d better play together.

Here in the States, it’s exciting to see the summer tour with Alice Cooper. It’s great that you’ll get the exposure of playing large crowds here in the U.S. with a new album in tow, and Cooper seems like a good match with you guys.

Alice is a great guy and a very good friend. We’ve done numerous shows together around the world. Concert ticket prices, they’re high. So if you’re going to get somebody to come out, you’d better give them some value. I think that between us and Alice, that will be a great night out. And believe me, Alice is one of the toughest acts in the world to follow. He really is. Because he just puts on such a total show. The only problem that we have in the States is the splitting of generations, trying to actually get new music through is difficult. We’re lucky -- we have a lot of songs from the past that people want to hear and you know you have to play them. People would be very unhappy if you didn’t do “Highway Star” and you didn’t do “Smoke on the Water” and you didn’t do “Perfect Strangers” and you didn’t do these other songs. You still have to find a way of blending in this new music and if the outlet for that new music isn’t there -- and it’s tough to find it now. Classic-rock stations will advertise your new record, and then they’ll play “Smoke on the Water.”

That’s really tough, because familiarity is a great thing, and when you hear things on the radio, you get used to them and you see them live, you’ll accept it a lot easier. So that is hard work, convincing people that you’ve got this new music out and it’s pretty good, please listen to it. That’s the hardest thing we find now. We’re lucky, we have this wonderful baggage from the past, which is the bulk of the show -- of course it has to be. But the hard thing is really making people accept new music when there’s no media outlet in a general way for people to actually access it. It’s quite a problem.

At the same time, it’s good to see you guys stick to your guns and get that new material in there. Because certainly seeing you guys tour the last record, the new material goes over really well and fits really well in the set alongside those classic tracks. It has its place.

The reason it goes over so well is because it’s good stuff! But with the radio system, which was a little bit more encompassing than what we have now, more like we had in the past, where there was such a huge horizon of musical styles that would fit everybody’s tastes, it’s a little more difficult now. So you really are relying 100 percent on the fact that apart from your truly dedicated fans who will have bought the record and know the songs, a lot of those people will never have heard it, because there’s no radio station going to play it and that’s hard work. You’ve really got to know that what you’re giving them is so s--- hot that they will take notice of it.

The band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame last year. How was that experience for you?

It was a night. [Laughs] It’s fine, you know. Really, these awards, it’s not very rock 'n' roll, really, is it? It’s very Hollywood. I sort of understand the Oscars, where everybody’s slapping each other on the back. I don’t know if it translates into rock 'n' roll that well. It was okay. Really, for our fans, it was a justification. I think for the musicians in the band, it was nice to be there for our fans. But it doesn’t change much. Had the club stayed a little more exclusive, I probably wouldn’t be saying it this way. But it’s called the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It’s not called the Light Entertainment Hall of Fame, which is sort of what it’s turning into. There are people there who have nothing to do with rock 'n' roll, so it gets a bit diluted and probably a little less important than it actually should be. And so it was a nice night -- my wife and I had a lovely weekend in New York. I got a free mug, a T-shirt and a little statue. So it was pretty good.

How’s your health been?

I’m good. I had a little event last year in about June. I had a very, very minor stroke, which frightened the s--- out of me, but I got fixed up real good. So long as I take these four tablets once a day for the rest of my life, there’s no reason why it should ever happen again. But it was pretty scary for me. My right hand had nothing to do with the rest of my body, to the point that I couldn’t even sort of scratch [myself]. I just had a lump of flesh on my right side. But it came back pretty quickly and the doctors told me that I’d been very lucky. It’s what is called a TIA rather than a full blown stroke, and I recovered. Blood pressure is great, heart is great, so I’ve been a lucky guy.

For those to be the first Deep Purple shows you’ve missed since the band formed in 1968, that’s a pretty solid history of showing up for work.

Yeah, it broke my heart to do it, though. You think that nothing’s going to happen to you, that you’re bulletproof and immortal, and then suddenly nature shows you that you just ain’t.

Well, the way you described it, it sounds like it was a pretty terrifying experience. I’m glad you’re back in a better place.

It was terrifying for about 10 or 15 minutes, and then you go into self-preservation mode. You go, “How do I get out of this? What do I do? What do I do to look after myself? That’s what kicks in straight away.” Get on the phone, get somebody there, get me in the hospital. That all happened in 20 minutes, man. I was so lucky.

Deep Purple Albums Ranked Worst to Best

More From Ultimate Classic Rock