When Bob Dylan Unplugged for ‘Good as I Been to You’

When the river runs dry, Bob Dylan retreats to the well. At least that’s what Dylan observers, critics and obsessives think: When the man generally regarded as the greatest songwriter of the rock ’n’ roll era encounters an outbreak of writer’s block, he returns to the pre-rock songs and sounds that first inspired him.

It’s something he did in the mid-to-late ’60s – with the Band, and Big Pink and The Basement Tapes. Ditto 1970 (given the many traditional and cover songs on Self Portrait) and 1986-87 (when a couple of records were split between original and others’ material). After 1990’s Under the Red Sky was greeted by such a poor reaction from fans and critics – and eventually Dylan himself – the musician was again in need of some old-time inspiration in the form of songs that had stood the test of decades and even centuries.

“Those songs worked their way into my own songs, I guess, but never in a conscious way,” Dylan said in 1993 via Warehouse Eyes. “It’s like nobody really wrote those songs. They just get passed down.”

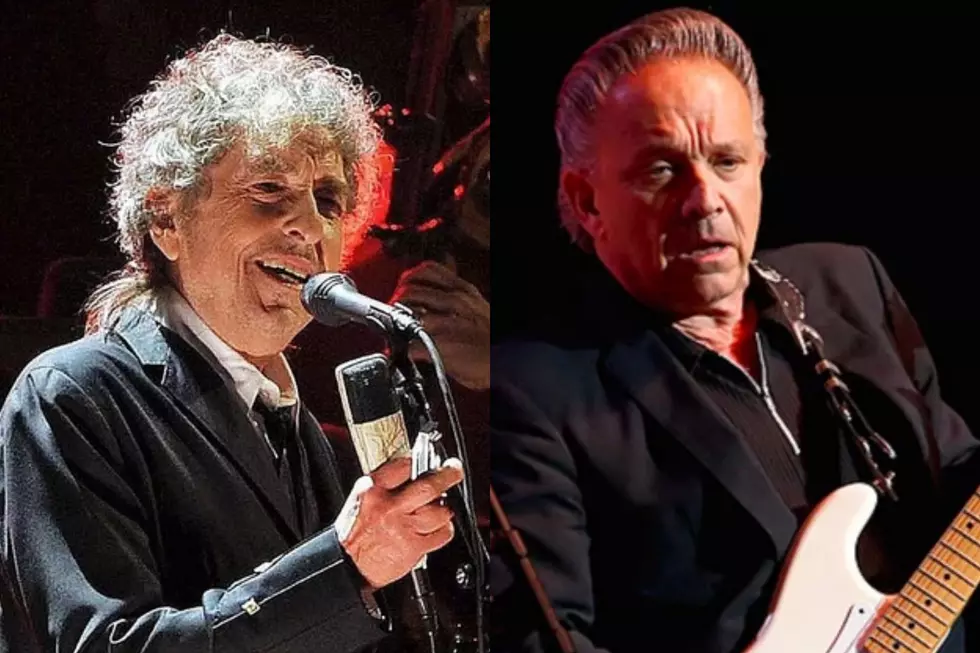

Good as I Been to You was begun under the auspices of contractual fulfillment, according to friend Susan Ross. In 1992, Dylan was recording music because he was obligated, not because it’s what he desired. He arranged studio time at Chicago’s Acme Recording Studio, where he recorded traditional folk tunes, religious songs and other covers with a backing band in sessions overseen by longtime collaborator David Bromberg. Then he went to Europe for a short summer tour.

When Dylan returned to his home in Miami, he decided to record additional material for the new album. But instead of booking another professional studio and a bunch of studio hands, he set out to lay down tracks in his garage studio, with only producer Debbie Gold and sound engineer Micajah Ryan. Otherwise, Bob would handle everything – vocals, acoustic guitar, harmonica … just like the old days.

The idea was to intersperse the full-band recordings with a few stripped-down tracks – not unlike what he had been doing on tour with mid-set, acoustic performances of traditional tunes. It was sort of a palate cleanser. But as Dylan continued, this method appeared to speak to him creatively in a way the Acme sessions had not. Initially, the engineer had only planned on being available for a couple days of recording.

“Then in comes Bob Dylan and all bets are off. There just isn’t anyway to prepare for a moment like that. Dylan was on a roll, and I didn’t get back to my family until a couple of months later …,” Ryan told Uncut. “It seemed Bob had a very strong idea of what songs needed to be on the record. My job was to record everything he did. … He consulted Debbie on every take. He trusted her and she was never afraid to tell him the truth, and, boy, was she persistent, often convincing him to stay with a song long after he seemed to lose interest.”

The sessions would include many public domain compositions, from the Irish, English and American traditions of folk songwriting. There was “Jim Jones,” “Blackjack Davey” and “Froggie Went a-Courtin’” alongside blues covers such as “Frankie & Albert” and “Sittin’ on Top of the World.” Better-known folk tunes such as Stephen Foster’s “Hard Times” sat alongside, perhaps, lesser-heard stuff like “Little Maggie” and “Diamond Joe.”

Pretty soon, the Chicago tapes were shelved (some would later be heard on Bootleg Series entries) in favor of this home-recorded material, which formed the entirety of Dylan’s 28th studio album. Not only were all 13 songs on Good as I Been to You covers (12 of them traditional numbers, with the exception of the R&B chestnut “Tomorrow Night”) the entire album was a solo acoustic affair – the first Dylan record to appear this way since 1964’s Another Side of Bob Dylan.

Upon its release from Columbia Records on Nov. 3, 1992, Good as I Been to You met with a warm – if not ecstatic – reception from listeners and critics, who praised Dylan’s back-to-basics approach, song choice and phrasing. However, some folk music aficionados also noted that the phrasing and arranging on this selection of songs owed a few debts to other acts that had previously performed the material.

They were especially incensed by an album credit that stated all songs were traditional (even though “Tomorrow Night” was written in 1939) and arranged solely by Dylan. But it was obvious to the some fans that the musician was leaning heavily on other artists’ arrangements, from Mississippi John Hurt’s take on “Frankie & Albert” to Paul Brady’s version of “Arthur McBride.” In one case, Australian folksinger Mick Slocum sued Dylan’s publisher because he had recorded the same arrangement of “Jim Jones” in 1975. Future pressings corrected some of these errors.

Whether a creative necessity or a contract filler, Good as I Been to You found Dylan hearkening back to the folk tradition – something he would repeat on the similar (though slightly bluesier) World Gone Wrong in 1993. Dylan has credited the approach to at least partially reigniting his desire to write and record more original material (such as 1997’s Time of Out of Mind and 2001’s “Love and Theft”).

“My influences have not changed – and any time they have done, the music goes off to a wrong place,” he said in 1997 via Behind the Shades Revisited. “That’s why I recorded two LPs of old songs, so I could personally get back to the music that’s true for me.”

Ranking Bob Dylan’s ‘Bootleg Series’ Albums

Why Don't More People Like This Bob Dylan Album?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock