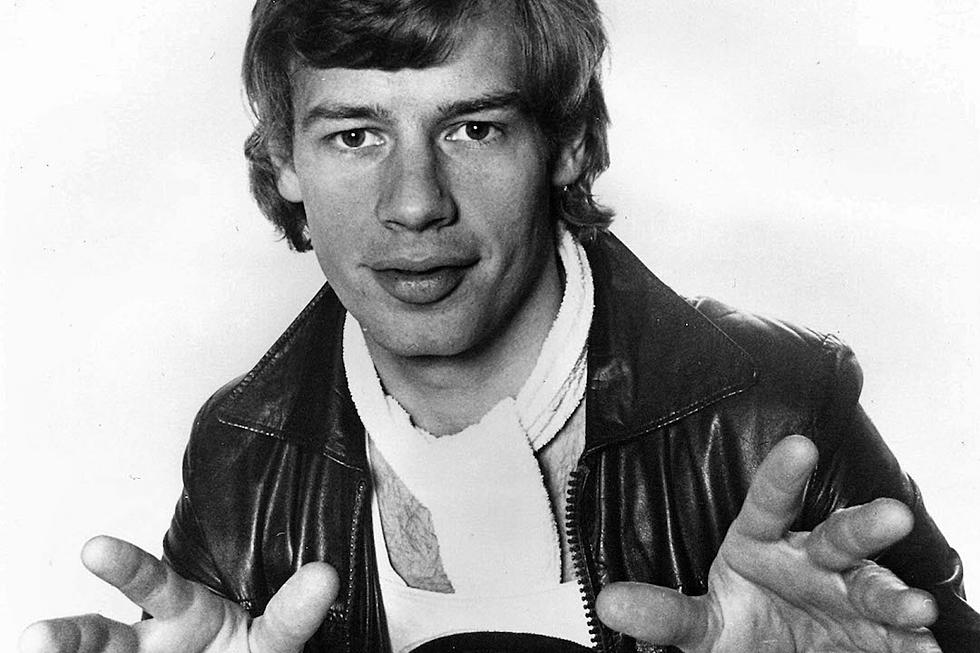

The Day Bill Bruford Announced His Stunning Departure From Yes

Bill Bruford's hall of fame career included eight studio recordings as drummer with King Crimson, and a brief but celebrated stint in Genesis. Yet his July 19, 1972 departure from Yes remains a central talking point. After all, they were at the peak of their considerable progressive-rock powers.

"'Why did you leave Yes?' That's been the bête noir of my career," Bruford said in a 1998 talk with Innerviews. "I actually became famous for a negative — for leaving a group, not for contributing to it."

Bruford's impact on Yes was, in fact, sweeping. A band co-founder, he ended up appearing on five early studio efforts, starting with their self-titled 1969 debut. Bruford's final trio of albums, 1971's The Yes Album and Fragile then 1972's Close to the Edge, confirmed their place in rock history. He was still in his early 20s.

"It was a good place to start," Bruford later told the Birmingham Post. "I was learning my craft, learning how to get on with other musicians, learning how to co-operate with a group – which is all very important especially when you're a prima-donna young drummer, who thinks he's played everything when in fact he's played nothing."

History actually shows that Bruford had quit once before. He'd planned to attend college in pursuit of an undergraduate degree, and informed Yes not long after they first got together. Bruford's replacement didn't work out, however, and so he returned just days before Yes took the stage at the Royal Albert Hall in support at Cream's famous November 1968 farewell concert.

That wandering spirit always remained, even as Yes struggled to find an early identity. (Bruford later lamented "the chaos of Yes, where nobody could agree what day of the week it was," in 2007's Genesis: Chapter and Verse. "How we in Yes ever got anything done, I still don’t know.") Constantly looking for new improvisational avenues, he pushed back against the kind of metronomic performances most rock bands demand.

In time, Bruford left the genre all together, turning instead to jazz. "In fact, what finally drove me out of rock n’ roll was the repetition," he remembered in Genesis: Chapter and Verse. "That’s what had separated me from Yes. Why I had found King Crimson so attractive was because they were way more open: ‘Surprise us, go ahead; let’s improvise, terrific.'"

King Crimson leader Robert Fripp's offer, Bruford said in a 1995 interview with the Beacon, was as straight forward as it was inviting: "'I'm proposing a band, and it has you in it, and it has a crazed avant-garde, improvising drummer called Jamie Muir, and it has a violin player [David Cross] and the best young bass player in London called John Wetton. Do you want to be in it?'"

Listen to Bill Bruford Perform 'Perpetual Change' With Yes

He did. Even decades later, Bruford's ex-Yes bandmates still seemed stunned by his exit – though, in time, they came to appreciate how it helped the now-retired drummer's career.

"He was there on so many levels in the beginning, at the foundation of what Yes became with Fragile and Close to the Edge," fellow co-founder Jon Anderson told Rolling Stone in 2016. "Then he goes and joins King Crimson. How dare he! [Laughs.] That killed me, I've got to tell you. I was in desperation for about a month because I was like, 'How dare he leave Yes to go join King Crimson!' I know what it was: It was for more freedom. He evolved, and got better and better."

Still, extricating himself from a band that had finally reached the million-selling plateau wouldn't be easy. Largely unaware of the details of his own contract, Bruford said he ended up having to buy his way out of Yes. "Incredibly, and as testament to my ignorance, I paid handsomely to leave the group that I had co-founded," he says in 2009's Bill Bruford: The Autobiography. "To the incoming [drummer] Alan White, I donated a handsome set of brand-new silver flight cases for his drums and half of my royalties to what was to become the platinum-selling album [Close to the Edge]."

Bruford never looked back. "If you've turned in the best album you're going to do with an ensemble," he told the Tampa Bay Times in 2009, "it's your obligation to move on."

He ended up recording three albums with King Crimson in the '70s, including Larks' Tongues in Aspic and Red, three more in the '80s (with 1981's Discipline as a high point) and then two in the '90s. Along the way, Bruford was also part of U.K., toured with Genesis during their first dates with Phil Collins as frontman, and reunited with Yes during the Union era. He ended up developing a detailed understanding of what made King Crimson different - and it only confirmed the wisdom of his once-shocking split with Yes.

"See, the problem with bands like Yes has been overconsumption of resources, greed on the one hand and indolence on the other," Bruford told Notes From the Edge in 1995. "Now this is, of course, where King Crimson is entirely different. King Crimson is on the whole an abstemious organization – not in the sense that you have to cycle your own bicycle to the concert, but money is consumed for the creation of music and music only. It's not consumed for any other reason. It's not consumed for vanity. It's not consumed to keep other people in business, or supply drugs, or anything else. It's consumed as much as is necessary to make the record, and generally speaking with good musicians."

While Bruford's former band ultimately found themselves chewed up by an industry endlessly searching for a re-run of Yes' 1983 chart-topping hit "Owner of a Lonely Heart," King Crimson stayed faithful to a completely different aesthetic.

"You're looking to make the record fairly cheaply, so there is a healthy profit," Bruford told Notes From the Edge. "Why do you want a profit? You want a profit so you can stay independent and that you don't have to have Clive Davis edit your single, or even tell you what the single is, or do anything. So, King Crimson is as free as the wind, and Yes looks like a songbird trapped in a cage."

Top 50 Progressive Rock Albums

The 'Silly' Phil Collins Joke That Went Too Far

More From Ultimate Classic Rock