How Steven Van Zandt Took on Apartheid With ‘Sun City’

After Live Aid, Farm Aid, Hear n' Aid and USA for Africa, rock fans could have been forgiven for assuming there weren't any causes left for their favorite musicians to champion in 1985 — but E Street Band guitarist Steven Van Zandt shattered that assumption with his all-star Sun City project.

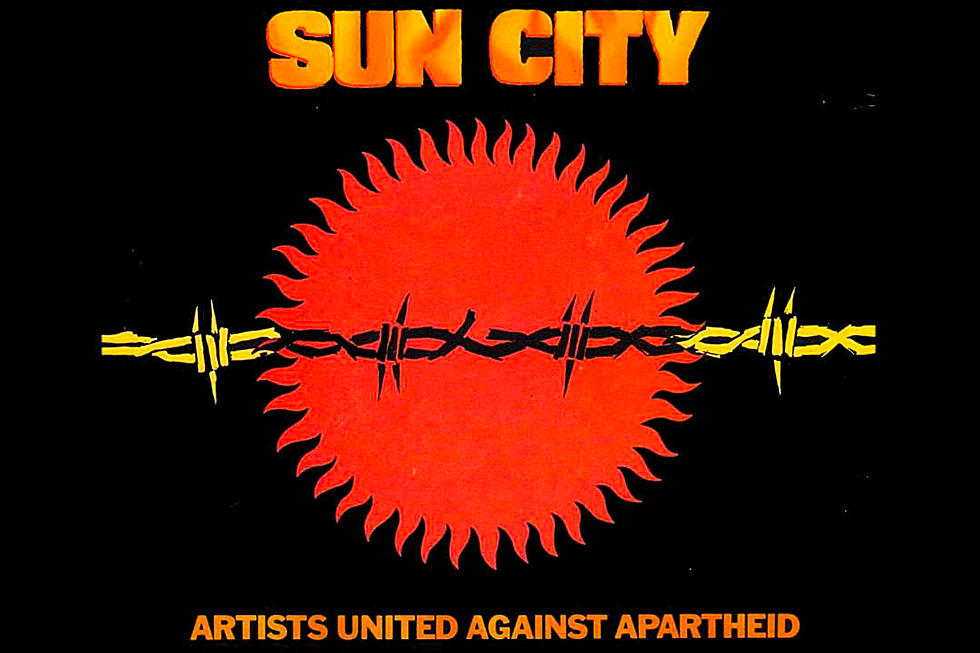

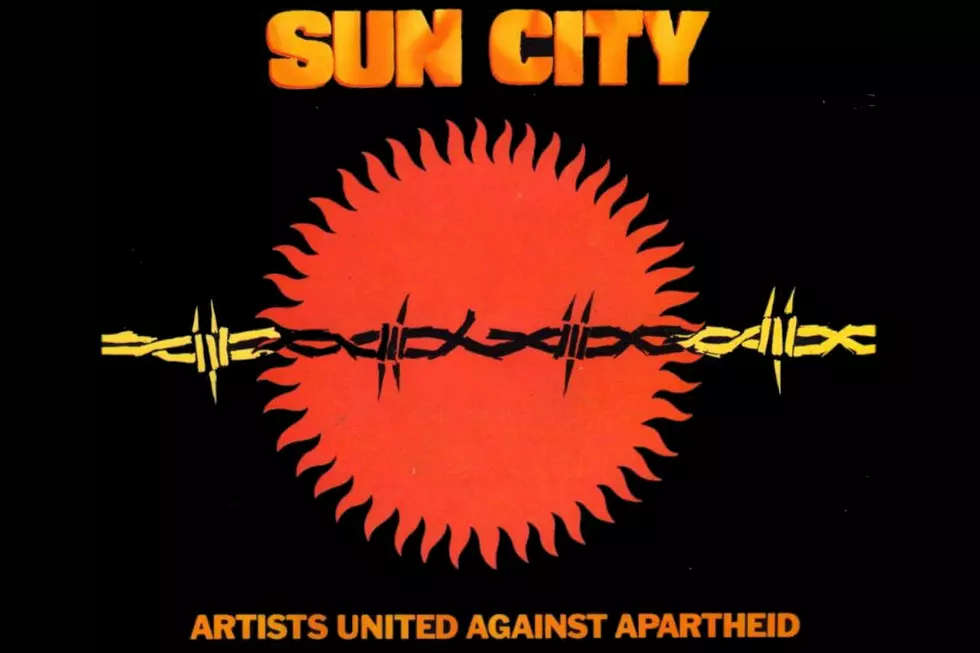

Released on Dec. 7, 1985, the Sun City LP was credited to Artists United Against Apartheid, a musical coalition Van Zandt assembled to help raise awareness of the system of racial segregation enforced by the governing party in South Africa. Unlike many of the era's socially conscious releases, the album wasn't put together with an eye toward raising money to help further a cause — in fact, part of Van Zandt's mission was to encourage a cultural boycott of the region in order to damage the South African government's credibility on the world stage.

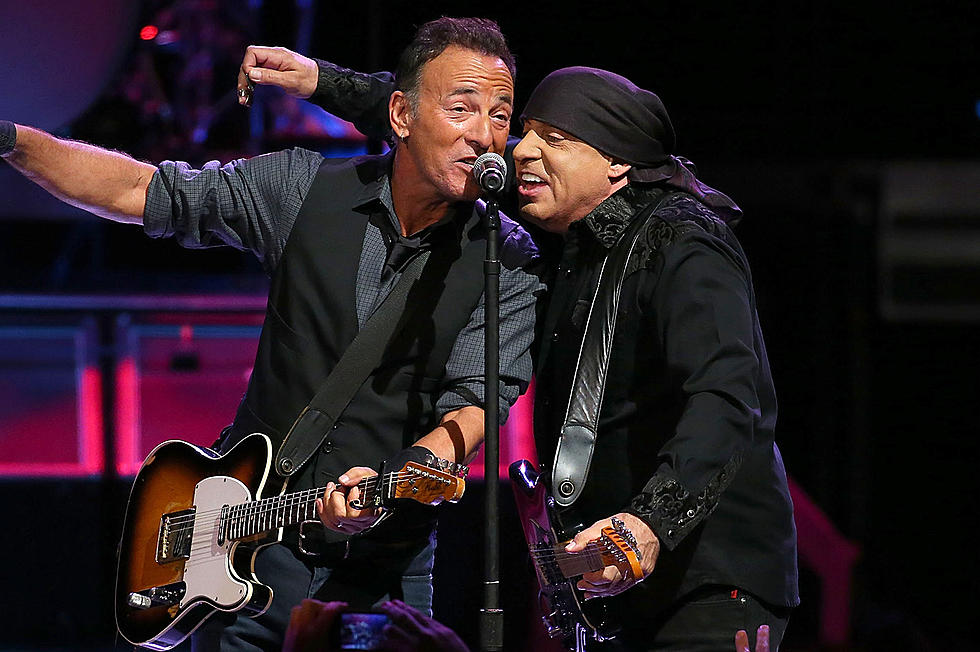

Even though Van Zandt had risen to prominence as a sideman for one of mainstream rock's more politically vocal figures, his years playing alongside Bruce Springsteen weren't a direct influence on his decision to pursue the Sun City project. Instead, as he later recalled, the record grew out of a general political awakening that would ultimately take him away from the E Street Band and spur a decade of activist efforts.

"It wasn’t an issue. It wasn’t in the papers. It wasn’t in the air. On my list, I had 44 situations around the world I was looking at as I tried to educate myself about what’s going on in the world, which I had never done [before]. I had grown up not being a good student in school or anything else," Van Zandt admitted. "I never read a newspaper. I was completely obsessed with rock 'n' roll until we broke through with The River, and at that point I said, 'Y'know, I wonder what’s going on in the world.'"

That question led him to travel to South Africa in person, where he absorbed firsthand the horror of apartheid — reflected not only in the segregated "self-governing" regions dubbed "bantustans," where millions lived in poverty-stricken squalor, but also in the deeply racist attitudes he witnessed as a first-time visitor.

"I was in a taxi cab and a black guy stepped off the curb, and [the white taxi-driver] swerved to hit him, [muttering] 'Fucking kaffir,' which means 'n---er' in Afrikaans. And I said [to myself], 'Did I just witness that?,' ‘cause I wasn’t really paying attention [at first]. And I remember that moment," Van Zandt said. "It just hit me like, 'Okay, these guys gotta go. This is way beyond another song on my next album. I gotta get some attention for this issue and do something about this.'"

Initially intending to address apartheid in a track for his next solo LP, which would arrive in 1987 as Freedom – No Compromise, Van Zandt instead approached producer Arthur Baker to help shepherd what quickly became an album-length project of its own — and one that attracted a wide variety of artists that ran the gamut from Springsteen and Van Zandt to Gil Scott-Heron, Miles Davis and Africa Bambaataa. It all started with the title track, which lambasted the ignorance of artists who accepted invitations to play at the Sun City resort in the bantustan of Bophuthatswana.

Watch Steven Van Zandt Discuss 'Sun City'

With Baker at the helm and assistance from journalist Danny Schechter, Van Zandt assembled a parade of artists for his "Sun City" song, which fit more than two dozen guests in less than six minutes. Lou Reed, Pete Townshend, Bob Dylan, Jackson Browne, U2, Peter Gabriel, Bonnie Raitt, Pat Benatar, Joey Ramone, Keith Richards, Ronnie Wood and Daryl Hall and John Oates were just a sampling of the rockers who agreed to participate, appearing side-by-side with luminaries from the jazz world like Davis and Herbie Hancock and R&B legends such as Bobby Womack and George Clinton, as well as an assortment of rising hip-hop stars that included Kool DJ Herc, Grandmaster Melle Mel and Run-DMC.

That eclectic blend would later prove to make "Sun City" something of a hard sell at radio, but it was purely intentional. "What we wanted to do was to break down the apartheid in music in our own country by having musicians – international artists, rap, rock, Motown, jazz – that were usually segregated in America," Schechter pointed out. "There would be a black station, a white station, a jazz station and the like and put all of these currents on one album as a united statement against apartheid. Fifty-eight stars agreed to be part of it, and the fact is, many more wanted to be part of it when they found about it. There were no more lines to sing."

Van Zandt found no shortage of support within the artistic community, leaving him with a surplus of material that grew to fill a seven-track, 45-minute LP. Befitting the genre-ignoring assemblage he'd lined up for the title track, the Sun City album covered a broad swath of musical ground: Gabriel, who'd helped turn attention toward apartheid earlier in the decade with his song "Biko," contributed "No More Apartheid," which started out as a seven-minute drum piece, and the record's first side concluded with the rap track "Revolutionary Situation," which sounded like a jarring transition at a time when rock and hip-hop were still seen as completely musically distinct. That freeform attitude carried over to the second side of the album, which featured a seven-minute jazz track as well as "Silver and Gold," a last-minute addition from Bono with Richards and Wood.

If Sun City's message landed on largely receptive ears among Van Zandt's peers, it still wasn't entirely without controversy. A number of artists — as well as political pundits — argued that a boycott of the region would do more harm than good, and others, like Paul Simon, took the position that art transcended politics and shouldn't be forced to take ideological sides. The debate ignited emotions on both sides, and didn't lend itself to easy answers, though it did provoke some of the decade's most important music: Sun City helped motivate the political efforts that ultimately ushered in apartheid's demise in 1994, while Simon's South African album, 1986's Graceland, exposed millions of listeners worldwide to the beauty of the nation's music.

To Van Zandt's credit, "Sun City" made its political points clearly and forcefully, even going so far as to name-check Ronald Reagan in the lyrics at a time when he was riding historic highs of popularity in the polls. Perhaps for that reason — as well as his willingness to feature an assemblage of artists that many radio programmers felt were neither "rock" nor "rap" enough to put in heavy rotation at either format — the single brushed the bottom reaches of the Top 40, while the Sun City LP rose no higher than No. 31. Further stymied by PBS' unfortunate refusal to air a making-of documentary, the record never quite reached the audience it should have, but commercial success wasn't really what Van Zandt was after. As a platform for raising awareness of an issue that many people remained ignorant of, the album served its purpose.

"It was completely successful, and that's such a rare thing," Van Zandt told Rolling Stone. "Issue-oriented events and records can be very frustrating, because you really don't see the results, whether it's feeding people in Ethiopia or raising money for AIDS research. Our goal was to stop performers from going there, and to this day no major artists of any integrity have played Sun City."

Bruce Springsteen Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock