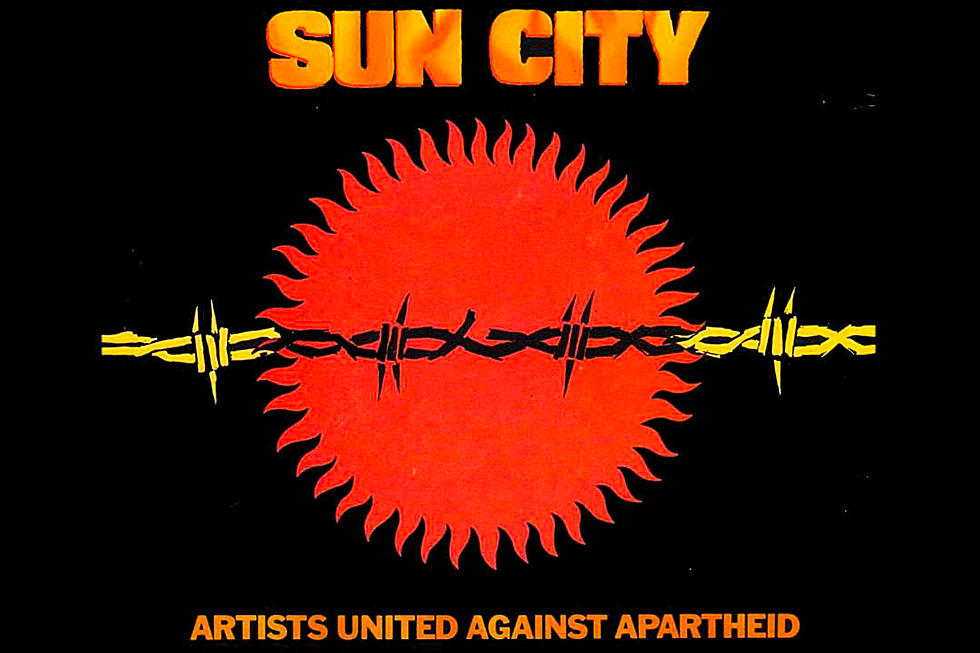

Steven Van Zandt Recalls Spark That Lit All-Star ‘Sun City’ LP

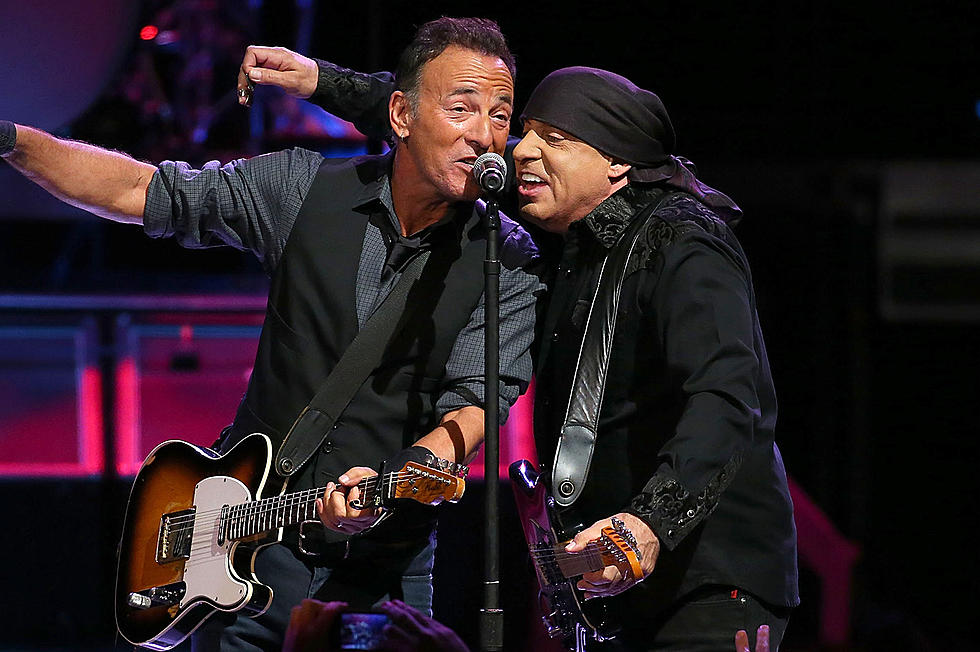

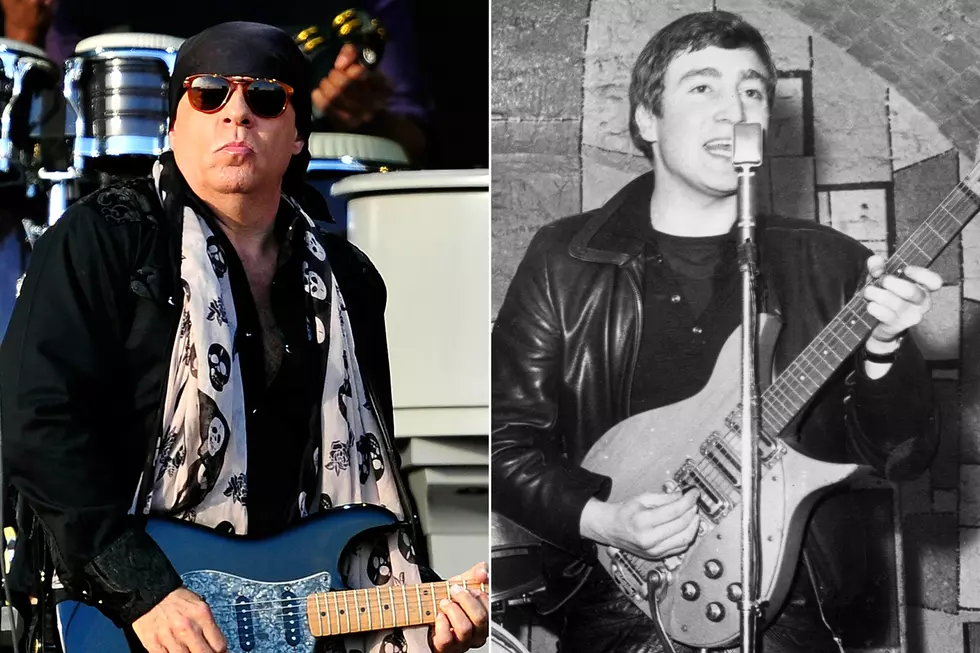

The 1985 all-star album Sun City came from an unexpected place. In his new book Unrequited Infatuations, Steven Van Zandt recalls how he was sitting in a Los Angeles movie theater waiting for Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless to start, and a song began to play that knocked him out.

After the film ended, he knocked on the projectionist's door to find out who had performed the song. "Peter Gabriel," Van Zandt was told. "Biko." "I had never heard of either one of them," he admitted.

With a bit of research, Van Zandt uncovered the story on both people. He was troubled by the story of Stephen Biko in particular, a Black anti-apartheid activist in South Africa who had been murdered in 1977 while in prison.

Van Zandt, who had already made a "list of America's dubious and mostly hidden foreign entanglements since World War II," added South Africa to his list and got to work.

He writes in depth in Unrequited Infatuations about how the Artists United Against Apartheid album Sun City emerged from a session for a single song. Van Zandt was able to enlist nearly everyone on his wish list for the single and LP, with a few exceptions - including Frank Zappa, who told Van Zandt that he wanted no part of his "meaningless bullshit record." He got a different negative response from Paul Simon, who later questioned Van Zandt's support of Nelson Mandela, wondering how the former E Street Band guitarist could get behind someone who "obviously was a Communist."

Van Zandt shares with UCR some other memories of the project.

When you did Sun City, how much did you think about potentially getting blacklisted by the industry for the whole thing?

I didn’t really think about that. I was getting death threats and that kind of stuff, which you would expect. The white supremacists were already there and existing. They didn’t come out of the woodwork until these previous four years, and suddenly they’re celebrating their white supremacy. But they were there, even then. I didn’t realize how dangerous I had become in the corporations’ eyes. Feeding people in Africa is one thing; bringing down governments, you know, that makes people a little bit nervous. [Laughs] And we did. Those 50 artists and all of those engineers that worked for free, and all of those musicians. Man, it was a worldwide movement. We only just kind of gave it a little spark.

We gave it a spark that really did put it over the finish line. But it already had existed for years and [was] very strong in Europe. It wasn’t much of an issue in America, though. That’s kind of how we snuck up on it, I think. People didn’t see us coming. But around the world, it was big. I mean, the unions in Europe, man - if you were on that U.N. blacklist, you weren’t going to work. They were really serious. We kind of just jumped onto that train that was already moving, but like I say, we gave it that final kick that I think got it across the finish line.

I wasn’t aware how organically Sun City became an actual album. It seems like it would have been cool watching those moments, which were envisioned initially as guest appearances on a track evolve into their own songs.

Yeah, yeah. We do have a documentary that came out at that time. We won the International Documentary Association Award for it, actually. We are now talking about really updating it. [We now have] hours of footage that should be seen, interviews with everybody on that record. And half of ‘em are gone, man. I want to definitely update that documentary. I’m talking to Hart Perry, who did the original [film] and some other people who can get that going. It’s just a great moment in time, and it really does document how it became an album from one song in a totally organic way. You’re so right.

Watch 'The Making of Sun City'

It seems like anybody who encountered Miles Davis has great stories. Your experience was no exception.

I really couldn’t believe it when he walked in. I mean, he’s just one of those guys that’s just a real mythological dude. He’s just one of those very, very rare cats that are something else. Some other species. I had him on my list right away. I happened to be lucky - one of my old soundmen was his soundman. I had that way in and hit upon something that happened to be a really big passion of his - [something] that you couldn’t have really known about. We kind of got lucky with that, but he was really, really into it. For him to show up, I mean, he walked in at, like, two o’clock in the morning, and he just doesn’t do those things. I can’t think of another example of some multi-artist thing that he took part in. I think it might have been the only one. But he was really, really serious about it.

He played for like five minutes. I had 10 seconds of him in the intro and 10 seconds in the middle. I’m like, “I’m not leaving four and a half minutes of Miles Davis on the floor, what are you, crazy?” [Laughs] We got lucky and called up Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Tony Williams, and said, “Will you come in?” They were into the subject matter also and the issue, and they came in. They played to what he had played, and boom there was another complete song. Completely legitimate and really quite artistically interesting. That’s how it went. The rappers - Melle Mel does a rap, boom, Arthur Baker turned it into a song. Gil Scott-Heron, rapping, we made that into a montage of news footage and cool stuff.

Peter Gabriel came in and just started chanting. Weird African chant, out of nowhere. He’s just expressing the pure, painful emotion of it. It was his song “Biko” that got me into it in the first place. He just had this cry from the soul. Then he started harmonizing with himself and then Tom Lord-Alge, I think it was, and the drummer, came in at night and put some drums on it. Boom, there’s another song. Bono wrote a song for the occasion. So, it was the ultimate organic artistic endeavor as it turned out, which we didn’t plan at all. We were hoping to get five or six artists who take part in the single. One from each genre, you know, just to have everybody kind of represented. And boom, it turned into 50 artists. Danny Schechter, Arthur Baker and Hart Perry, without those three guys, it wouldn’t have happened.

Listen to Miles Davis' 'The Struggle Continues'

You got nearly everyone you reached out to: Gabriel, Davis, Bob Dylan. It’s a really impressive thing to walk away with.

We were just very lucky, I think. I mean, it’s just good timing. A lot of life is good timing. We just happened to hit the right subject at the right time, even though we were kind of educating a lot of the people who took part in it. We were kind of educating [them] as we went. Some had heard about it. They knew a little bit about it, but in the end we made them all experts on the subject. Everybody wanted to participate in that issue. Prejudice continues to be a huge factor in our own country, which is one of the reasons why we did it. But it was down to pretty much slavery [in South Africa]. It was just so distasteful that people wanted to participate in it, and I was lucky. I think they sensed the fact that I’m a results-oriented guy. I had ADD long before it was fashionable, man. I don’t have the patience, and I completely respect anyone who does have the patience to feed Africans, and then they’re starving again next week and you feed ‘em again. And you feed ‘em again. I’m like, “Why are they starving? Let’s fix it.” That’s how I think. I don’t have the patience to gain two inches and go back one inch. I always feel like I’m trying to catch up. I’m kind of behind, and I don’t have the time. I hate wasting time.

You write in the book about how you weren’t familiar with Peter Gabriel’s music until you heard “Biko,” which speaks to something that I hear a lot from artists: You’re so busy working that sometimes you can have somebody like Gabriel, who was with Genesis and had a solo career, but until you heard “Biko,” he wasn’t on your radar.

Yeah, it just so happened that’s one genre I never got into, the whole prog-rock thing. I probably appreciate it more now. But at the time, you are who you like, and you’re building your identity. They just didn’t fit in. They were in that muso world, the world of more sophisticated musicians that, frankly, I didn’t have any interest in. I’m a song guy. I’m song-oriented. I start losing patience after two and a half minutes. [Laughs]

Back to the ADD.

[Laughs] Yeah. That’s just how I am, and that’s how I program my radio stations. That’s how I go through life. I’m just, like, “Action, man! Let’s keep moving here! Life is just too fucking boring! Let’s do something about it, please!”

The book uncovers a pretty significant beef with Paul Simon. How surprised were you when that went down?

I really like Paul. I really do. We’ve had some great conversations through the years. I completely respect his work. He’s one of the great writers of the second generation. You know, for him to be competing with the British Invasion, as he did and holding his own, I mean, that’s quite an accomplishment in the ‘60s. But this was just one issue that we just couldn’t agree on. To this day, he still thinks he’s right. You know, it’s like, “Paul, we proved that we were right and you were wrong!" He just doesn’t want to hear it. Because he has a different philosophy about things. I understand that, but to go against Nelson Mandela and go against the ANC, the PAC, AZAPO ... you know, the entire anti-apartheid movement and say that you know better than they do? That was a little bit arrogant. A little bit.

So he has a little arrogance in him, as we all do from time to time. I was trying to keep the family of music together. That’s why I ended up not criticizing the artists that had played Sun City, you know? I said, “No, no. They were manipulated. They were fooled into doing it. Let’s give them the benefit of the doubt, and as long as they don’t go back, let’s just forget it.” That’s what we did. Everybody got removed. I took everybody off that U.N. boycott list who had played there. I said, “You know, they were manipulated, let’s give them the benefit of the doubt.” In the end, we kind of kept the musical family pretty together with the exception of Paul, who went off on his own.

He was making great music, but at that point the priority was not spreading South African music around the world. The priority was freeing South Africa from slavery, [the time could come] later for the South African music. We had some South Africans on the record ourselves. But it was just one of those things. He was the one exception. I was never mad at him, really. I actually like him.

Watch UCR's Complete Interview With 'Little' Steven Van Zandt

Top 100 '80s Rock Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock