How Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler Influenced Daniel Lanois

Daniel Lanois has always thrived by doing things differently through his production work with artists like Bob Dylan, U2 and Peter Gabriel. He treasures the moments that sometimes transpire spontaneously as he's just hanging out with friends like Steven Tyler of Aerosmith.

But his newest album, Player, Piano, allowed Lanois to revisit past inspirations in a new way. With the quarantines in full swing, Lanois found himself landlocked in his Toronto studio, but his thoughts would carry him virtually elsewhere, to other lands – and past collaborations, without ever leaving his home base.

The new record functions as a similar type of soul-stirring journey. Lanois joined us to discuss how it sprang to life, while also revisiting some fun memories from his career.

Player pianos were pretty fascinating to me as a kid, so I was instantly drawn in by the title of this new album.

Oh, same with me. When I was a kid, I heard a piano playing with nobody sitting at it. I thought, “Oh my goodness, how did this ever happen?” Before records, it was a way of hearing familiar songs played even though you had no piano-playing skills. So that’s the origin of the player piano. They were rolls, really, a little bit like those tiny music boxes [imitates the sound] that have little holes in the paper. I was curious about how that worked. I found out that was the purpose of it, that long before recorded music, we could have favorite songs being played in the corner by an automatic piano. [Laughs.] How wild is that? It’s also the name of a Kurt Vonnegut novel. It was suggested to me by my Irish friend, Simon Carmody. I asked him, “Do you have a good title for me, Simon?” Because he’s a smart writer. He said, “Well, how about, Player, Piano. You’re the player, there’s the piano. It’s self-promoting and the Kurt Vonnegut reference is not bad.” And then we get to talk about the technical part of what a player piano actually is, so there you go.

Listen to Daniel Lanois' 'My All'

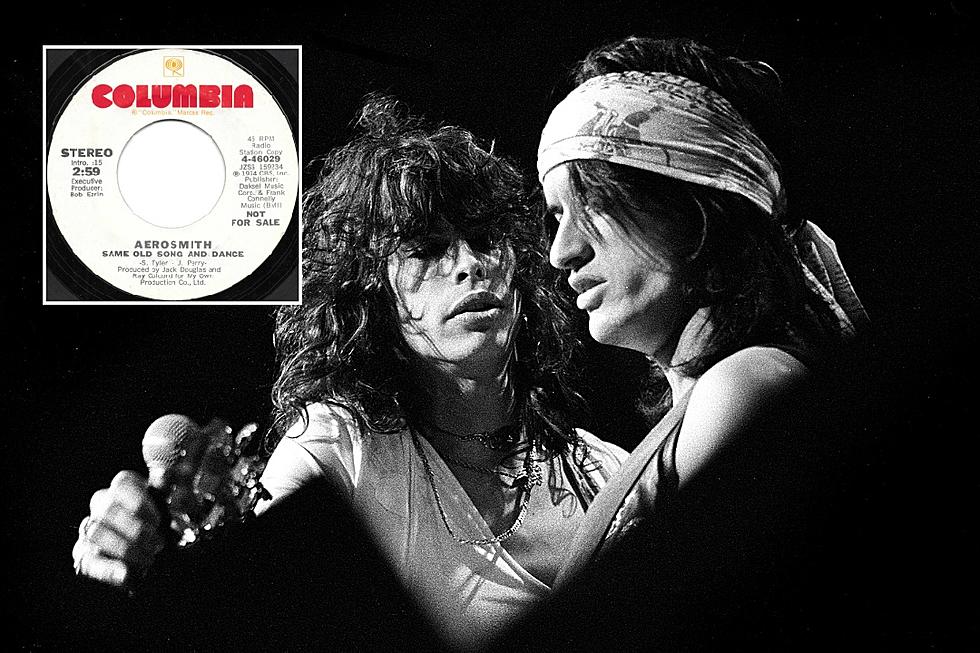

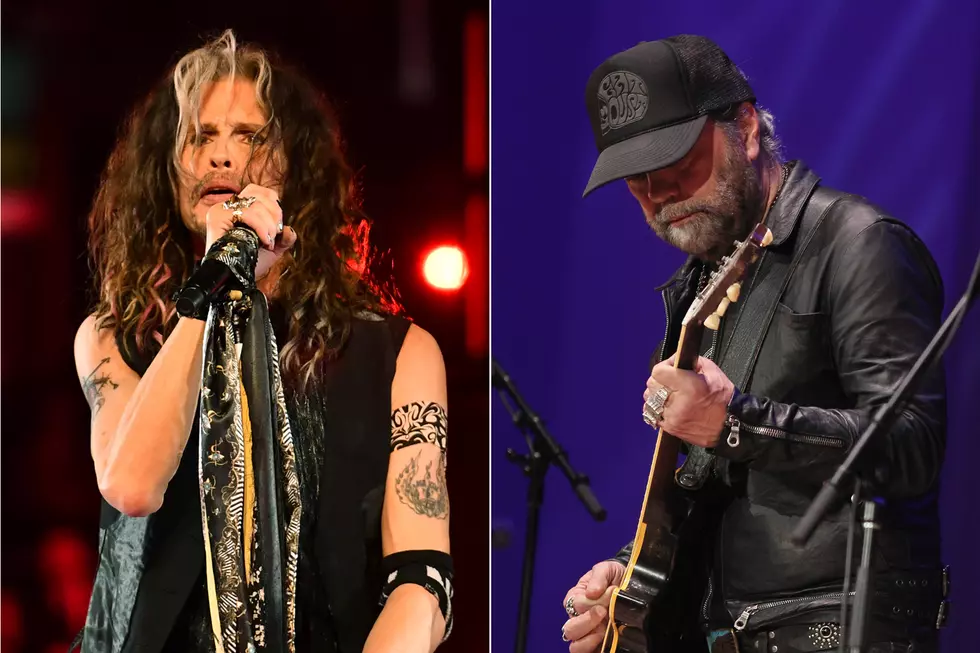

Steven Tyler helped to influence your approach for "My All," which opens the album. How did that unfold?

Steven and I have a mutual friend. His name is Justin Murdock. He's a music lover and a great guy, and he invited Steven to come to my place. We had a nice night of exchange and we had a great conversation and played a little music. We did some jamming. He went to the piano and I noticed that he was holding a steady chord on the right hand and moving the left hand I said, “Oh, tell me a little bit about this!” I heard a little bit of “Dream On” in the technique and I thought, “Well, that’s a cool thing to do, [demonstrates the section] with the right hand, steady. So you move the left hand and stay static on the right. I used that little technique on “My All.”

I spoke with Joe Perry and we talked about how Steven Tyler started as a drummer, which also adds something to the whole picture. But beyond that, you have a history of surrounding yourself with deep thinkers. I would imagine you learn a lot from those collaborations personally.

I’m glad you mentioned all of that because that’s the nature of collaboration. It allows information to be exchanged. Of course, if I’m sitting at the piano with Steven Tyler, I’m going to watch what he’s doing. He’s a great artist, writer and singer, so some of his thing will jump on me. Some of my thing might jump on him. He went to the drums on the same night, by the way. We did a little bit of jamming, which was nice. But you know, imagine sitting in a chair next to [Bob] Dylan for the making of a couple of albums. Obviously, by proximity, the exchange happens. It’s good for everybody if things are going well musically. Obviously, there will be some back and forth, and we hope to all come out of a project having made a record with a grander vision and more information to operate by.

Bono was the connecting point between you and Bob Dylan, which is a pretty great intersection of musical minds.

Yes, Bono was the agent for Bob and I working together. I was already in New Orleans making a record [1989's Yellow Moon] with the Neville Brothers. Bob was on tour coming through New Orleans and he stopped by. I believe he was curious about how we did things. We had set up in one of these unlikely locations. I had rented a six-story apartment building, a beautiful place, I think, built in the '20s. We had all six floors of the building with the studio on one floor and Charles Neville living on the first floor, me on the top and the rest of my crew and so on. So we had a little bit of a Brill Building [thing] going. Dylan was just fascinated with this pop-up that we had built for the making of a record. There was just something in it that smelt of commitment and devotion, to build something for the making of a record. I think it resonated with him that we were renegade, and we need to be reminded that everybody was renegade when they started. I’m sure that includes Bob. [Laughs.] We hit it off that way. He heard the music and loved it. We had cut a version of “With God on Our Side,” one of Bob’s songs. It was deep and powerful and I think he really appreciated that we struck a nerve.

You use a Roland 808 on "Twilight" on this new album and you also used that on the Oh Mercy album that you did with Bob Dylan. How did he react to the Roland 808?

Dylan didn’t have much to say about the Roland 808. We sat in two chairs as if we were sitting in the kitchen playing guitars. Bob played my guitars. I had already set them up in such a way that if it was acoustic, I used a pickup on the acoustic. I went to a little amp around the corner, isolated from the singing – because I wanted to make sure that if Bob changed some lyric lines, it would be viable that we could replace a line without having the old lyric bleeding through. The Roland 808 allowed us to be operating at a fixed time, which meant that ultimately, I could then apply my echo treatment to the songs. The track on that record that displays what I’m talking about is called “Most of the Time.” [Imitates the rhythm of the section.] So all of the echoes are perfect because we’re dealing with metronomic time. It allowed Willie Green to overdub the drums and so on. The production or the angle had the advantage of fixed time. I think Bob appreciated that we didn’t have to have a lot of people around. It was just an approach that I decided would be a good idea for the making of that record, because I wanted Bob’s vocal to be dominant. So we just had the 808 coming through a stage P.A. wedge at our feet. I was there, right by his side making sure that the grooves were locked. That was it. It became almost – I think of it as a kitchen hip-hop record.

Watch Bob Dylan's 'Most of the Time' Video

U2 had done three albums with Steve Lilywhite at the time you linked up with them. What are your memories of the band that you made The Unforgettable Fire with?

I met U2 when they were still kids. I was still a kid myself; I still am now. I was 27 and they were 19 and 20. We really felt the vibrant energy they had as kids, really, just coming out of their teens. They were very smart people with rock 'n' roll aspirations – but beyond that, they really wanted to bring the spirit of their music to the masses. They were looking to broaden their scope sonically. [Brian] Eno and myself had just come out of making some ambient records in Canada together, which was Brian’s vision, but we got really good with the processing. So we were able to bring something to the table that U2 were interested in. They were looking to spread their wings and discover new expressions sonically and otherwise. You know, it deserves to be said that Brian Eno is a brilliant mind and is a philosopher. He had lived a lot of life that the boys in U2 had not known yet. I had touched on [that] a bit by hanging out with him, so I think we brought great sounds, but more importantly, we brought a philosophical stance to their table.

How quickly did you find that collaborative spark with Brian Eno?

The spark with Eno happened immediately. I didn’t know a lot about him. There was a chance hearing of my work. He heard some of what I did in New York and he was coming to Canada to visit a friend. He booked some time at my place and had requested a particular synthesizer, the Yamaha CS-80, a great polyphonic machine. We got that in for him and he really appreciated that we were out of the beaten path of New York recording studios. Obviously, we were in Hamilton, Ontario. I think he liked the small-town mentality that we just had with us because we were from a small town – and it was an owner-operated studio, my brother Bob and I. We put a lot of love into the place and I think he really felt he was in the right spot to create this music. He got 100% of my attention and I took no other work. I devoted myself to making ambient records with Brian for a good few years before we went to Ireland.

20 B-Sides That Became Big Hits

Was Aerosmith’s ‘Night in the Ruts’ Doomed to Fail?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock