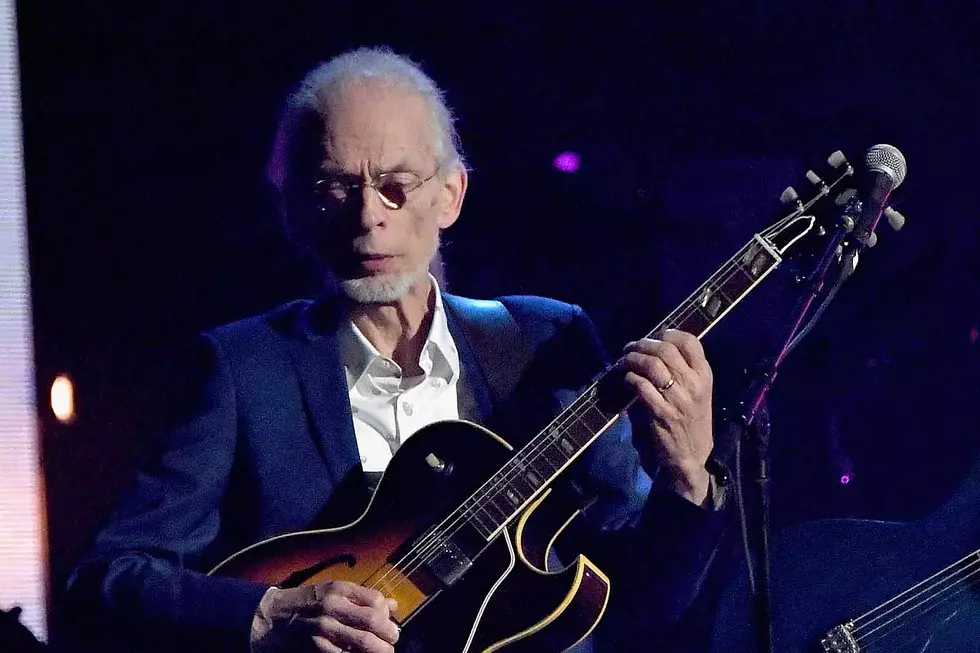

Steve Howe on New Yes Live LP, Feeling ‘Competitive’ With Genesis

Steve Howe, like the rest of us, is figuring out how to navigate the strange reality of pandemic life. "I'm human," he says, "and we're all in a new situation."

But the Yes guitarist also feels fortunate: He can continue to write and record at home, and he happened to wrap up several projects before COVID-19 upended tours for just about every band on the planet. His autobiography, All My Yesterdays, came out in September, two months after his latest solo LP, the tranquil Love Is, and Yes' upcoming concert album, The Royal Affair Tour: Live From Las Vegas, is slated for Oct. 30.

Howe tells UCR about projects past and present: explaining why Yes covered John Lennon's "Imagine" on the Royal Affair Tour, reflecting on the 40th anniversary of their underrated Drama LP and noting how the band felt "competitive" in the '70s with fellow prog-rock bands like Genesis.

It's a weird time to be a songwriter — touring has evaporated, but a lot of musicians are writing and recording at home. Have you been made much music since the pandemic hit?

I tend to write in batches. I upgraded my studio at the end of [2019] and delighted in it, and I realized as I released my book All My Yesterdays that I'd accumulated a lot of ideas but hadn't really developed [them] at all. Last year, about October or November, I was recording — it's all just sort of floating. To put it in perspective, this is nothing new. I remember when I did my [2005] album Spectrum, Tony Levin played bass on it in the same way that people exchange music now. It's been going on for a long time, and it's obviously something that comes in handy. It opens a lot of doors, but you have to know who you're working with very closely and understand the terms of engagement. I've never been short of projects I can do. I can rally around those and dabble with things and see what holds my attention the longest. That's how I got my album Love Is finished. It was really before what we're talking about now — I finished it in the middle of the year last year.

It's interesting that you mentioned Tony Levin. I spoke to him toward the beginning of the pandemic, and we talked about his experience with file-swapping. He was ahead of the curve in that department.

Back in 1999, I was sending songs out on tapes. You'd send them the tape physically and say, "Can you sing on that?" Then they'd send the tape back. In a way, it's been going on for [around] 25 years. Of course, it has gotten more refined — Pro Tools as a recording mechanism has gotten so amazing and keeps getting better.

Luckily, Yes recorded the Las Vegas date of the Royal Affair Tour, so you also had that project ready during this bizarre time. It's intriguing that you covered John Lennon's "Imagine" on that tour. Alan White played drums on the original recording — was that just your way of recognizing his contribution?

Mostly that. I had a spot with Asia for 20 minutes, and Geoff was also spotting with Asia, so there were opportunities to show another side. We thought we could at least do one tune with Alan that tells you something about him you hadn't thought about recently: that he played on "Imagine" and other great John Lennon tracks. When it came to learn it, [listening to] the John Lennon record, I thought, "What can you do with that?" It's so minimal and focused on a few things working together, which is a beautiful thing. And you have that great voice — and the fact that he's the originator of the song. I imagined being more melodic in my contribution. I wasn't going to start go, "Hey, I can do this [and that]." Of course, John Lennon's got a rock side, but the song wasn't treated like that. It didn't develop into another version of "Imagine." It stayed in that same beautiful mood. We thought, "We'd better be careful — we don't want to tread on anyone's feet by changing this." I did a steel guitar break, which I love to do. [It's like what] Ron Block does with Alison Krauss & Union Station — he plays the guitar with the right notes and doesn't do any more. There's no more than necessary. Just getting those movements and slides and slurs and expression into the idea of the song and not seeing it as an opportunity to go further than that. I like to think I've always been a fundamentally melodic guitarist — I've done solos and crazy things. But the thread that binds it together is melody and chordal [ideas].

The album also features "Tempus Fugit." That song first appeared on the underrated Drama, which turned 40 this year. Geoff Downes, who joined for that record, has a unique keyboard approach — much more minimal than his predecessors Rick Wakeman or Patrick Moraz. Did you initially worry he wouldn't be a flashy enough player for Yes, or did you think that was a healthy change anyway?

At that point, I'd worked with Tony Kaye, Rick Wakeman, Patrick Moraz … Rick Wakeman [again] and, suddenly, Geoff Downes. I was excited because he was very fresh [with] his equipment and the kind of sounds he could generate. It worked to push the envelope for us, and the evidence is that we played together in Asia as well. When I'd done the guitars on Drama at [London's] Townhouse studios, [Geoff] already had some parts to build around. He wanted to fill the shoes but also take it on and not be static — we couldn't be static because we had [singer] Trevor Horn as well. Geoff's playing, like Alan's, is exceptionally fine. We'd already written parts of "Tempus Fugit" before we met Trevor and Geoff. When we played that to them, they went, "We have some ideas. We'll [add] some ideas." It was a great collaborative opportunity, and it was very exciting — especially after [1978's] Tormato and the failed recordings in Paris. We hit a low spot in some ways. Making Tomato was tricky, and the Paris tapes just got to be boring. We just didn't have that sort of inner flame going. When we — Chris [Squire], Alan and I — were left to our own devices, we started things like "Tempus Fugit." We were like, "Let's just carry on. We know how to do this." We just carried on, and Trevor and Geoff walked into a situation that was already half-running but wasn't complete.

Chris had the amazing insight: He said to me one day, "Have you heard the Buggles?" [Hums "Video Killed the Radio Star"] I said, "It's good — it's almost as good as Abba." He said, "Do you have the album?" I said, "No." He said, "Get it and play it." I got it and went, "Wow, this production is great!" There was much more to it than the poppy [song] that I'd heard with girls going "la la la la" in the background. It's all beautifully [done], compelling material. Chris had the great idea [for them joining Yes], and I championed it and said, "I totally agree. There's something here that could work."

Trevor's vocals on that album are incredible. But I've read that, on the Drama tour, he requested some songs be taken down to lower keys. Why didn't that happen? What were those conversations like?

Everything was fine when we played tracks from Drama — that's what we wanted to play, and Trevor know exactly why he was doing what he was doing. When we rehearsed, we didn't instantly say, "We've got to change the key." We'd gotten used to playing in certain keys, and Chris and I liked that — "Yours Is No Disgrace" is in E, not E-flat. [Lowering the key] would have helped him tremendously, but I happen to know that there's a substantial change when you do that. I [occasionally] detune the guitar with heavier strings. That's about as far as you can go. You go a step further than that and, boy, everything sounds pretty awful. We once played "Going for the One" in D because we were so trying to get Jon Anderson to sing that onstage, and he didn't want to because he said it was too high. It wasn't [the same] anymore — it had some quality you didn't expect. I don't think Chris could risk having lower strings on his bass — it's a bass, for goodness' sake. He would have had to change his whole natural element. It could have been disastrous. When it comes to the heat of the moment and Chris just wants to go "bang," he's going to go "bang" in the old key.

I think Trevor would agree now that "And You and I" down a semitone in C most probably wouldn't have sounded quite right, but he would have sung it easier. We take full responsibility, and I take a lot of it — pushing Trevor to do this, even when it was difficult for him, wasn't fair, and we should be forever apologetic to Trevor about that. I don't think we were apologetic enough, actually, so here's another opportunity to say, "Sorry, Trevor." He did a fantastic job most of the time. He did his absolute best and gave everything he could. But that was a great shame. I'm really sorry we did spoil it for [him]. We should have been more considerate about the way we did those things.

When I interviewed Genesis keyboardist Tony Banks several years ago, after Chris' death, he mentioned that he "used to really love The Yes Album." Clearly you respect Steve Hackett's guitar playing, given your work with him in GTR, but I've always wondered what you think of the Genesis catalog. Do you have a favorite album of theirs?

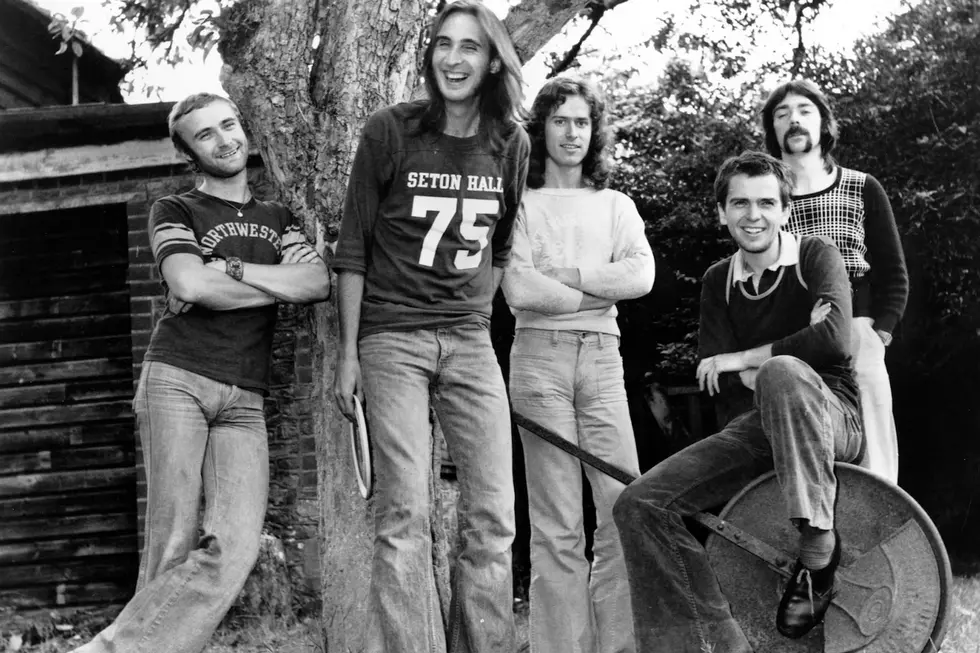

I don't know how honest to be, but I think Yes had a very British trait that nobody admits to: We were very snobbish. Do you know that word? Is it used in America? Maybe [used] about Brits? [Laughs] In a way, we were in a bubble. To be really honest — dangerously honest — we were highly competitive. In other words, we didn't mind what Genesis did, as long as it wasn't anything like what we did. We weren't going to be influenced by them. Unless this is just me, I think if you find the other [Yes] members to be in such an honest mood, they might agree to the same crime. We were particularly like this with ELP. We really appreciated Keith [Emerson] and Greg [Lake] and Carl [Palmer] — they were amazing! But we're not gonna listen to much of that because if we start playing like that, we're sunk. In a way, Yes wanted to think of itself — and this is very egoistical — as the ultimate rock band of the '70s. [Laughs] We weren't like we were because we thought we were pretty good. We were like we were because we thought we were amazingly good. I hope when you print this you put in my occasional laughs because you can see the way I'm saying this.

It's quite fun to look back at the youthful confidence — even before the success. The determination and drive in the music was so good. Bill [Bruford] playing drums and Chris playing bass. Tony Kaye was incredible. And Jon Anderson singing. For me to join that on The Yes Album, it was incredible chemistry going on there. It was the belief that we were better than everybody else. [Laughs] We weren't going to cheerleader [Genesis] in particular. I am laughing because it is kinda funny to say this — I don't know if anybody else is this honest about their own ego. I think we learned along the way that there's only one thing to have for other musicians, and that's the upmost respect. Because you know how hard it is. We mellowed a lot around Tales From Topographic Oceans, I dare say. But as we went on and Yes reinvented themselves on 90125, I think we all felt unshackled from this kind of belief that Yes were the ultimate band because we tried to create other ultimate bands instead.

In the early days, Yes were intensely collaborative, with ideas exchanged in the rehearsal space and people arranging on the spot. You had to be assertive to get your ideas across. Are there songs you look back on where you say, "I wish the band hadn't changed this?" Songs where you had a different original vision of what it could be?

Absolutely numerous, numerous versions. I did a whole series of eight CDs based on what you just talked about. We're bringing out Homebrew 7 at the beginning of next year. It allows me to see and explore and share the way I originally played [something] and, if people want to follow the trail, they can see how it becomes quite different. I'm not really shy. I know some musicians who won't reveal their structural developments in songs — you just hear the polished, finished versions that you all know and love. But I'm different — my home recordings really do talk a lot about my guitar playing, my work, my writing, my arrangement. There's a bit on Homebrew 6 from "Tempus Fugit" ["Edge of Town"] — that fast bit. It's swung like a jazz tune. [Mimics guitar riff] I saw it like that, and when we did work on what was to become that piece, I brought it out of the bag. That's what I do as a guitarist. When you're writing in a band, you do need to have ingredients — that's how "Tempus Fugit" came about. I had this crazy riff, and it was kinda jazzy, but if you play it on a Stratocaster with a tremolo, it's another creature.

Yes Lineup Changes: A Complete Guide

More From Ultimate Classic Rock