How Steely Dan Came Unglued With ‘Gaucho’

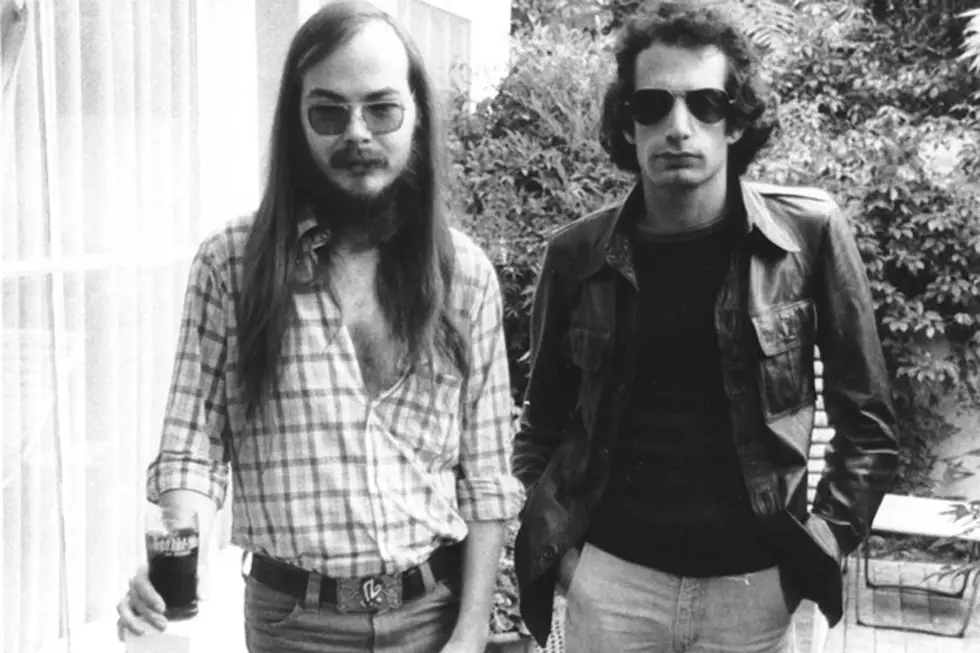

For much of their first decade as Steely Dan, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen led relatively charmed lives, professionally speaking. But during the sessions for what would become their seventh studio album, Gaucho, that luck ran out in a big way.

In fact, Gaucho didn't arrive in stores until Nov. 21, 1980 — more than three years after its predecessor, the critical and commercial smash Aja — a period during which the duo struggled with legal difficulties, health woes, and personal tragedy, all on top of a sustained, grueling attempt to raise their infamously exacting musical standards to an even higher level. It all added up to an album whose slender seven-track length belied the gargantuan effort it took to assemble it, and the exhaustion it left in its wake.

Going into the project, it hardly seemed like things would work out this way. Taking advantage of the clout they'd built up after Aja, Becker and Fagen opted not to rush into their next album, instead taking several months off to recharge their creative batteries. They also made arrangements to secure a fresh start for themselves on the label front, brokering a new deal with Warner Bros. after spending years at ABC Records.

The Warners contract, unfortunately, ended up being emblematic of the snakebitten circumstances that would surround much of Gaucho. ABC was a label on its last legs by the time Becker and Fagen secured their exit, but they were still signed there — and when MCA purchased the ABC catalog in 1979, they did so with every intention of making Steely Dan an MCA act. The ensuing court tussle would likely have kept Gaucho out of stores even if Becker and Fagen hadn't been painstakingly working their way through an arduous series of sessions.

Part of the problem stemmed from a case of culture shock. After living and working in Los Angeles for a number of years, Becker and Fagen relocated to New York for Gaucho, and found themselves frequently at odds with the dozens of musicians enlisted for the sessions — most of whom were among the best and brightest the city's studio scene had to offer. With the crew called upon to play the same songs and parts for hours at a time while the duo searched for the perfect take, tempers occasionally flared.

Listen to 'Babylon Sisters'

The chemical excesses of the era were also starting to catch up with Steely Dan — particularly Becker, whose worsening drug problem contributed to Gaucho's slow development and exacerbated a particularly dark period in the guitarist's life. His longtime girlfriend, Karen Stanley, died in their apartment after overdosing in late January 1980 — a tragedy further compounded when her family launched a lawsuit against him the following year, accusing Becker of exposing Stanley to the lifestyle that killed her. He survived his own brush with death in April 1980, when he was hit by a taxi, suffering injuries that sidelined him for six months and reduced his participation for a portion of the album to a series of telephone calls.

Technology also conspired against Steely Dan during the Gaucho sessions. The problems started early, when one of the first tracks earmarked for the record, titled "The Second Arrangement," was largely erased by an assistant engineer who — having been told by producer Gary Katz to prepare the tapes for playback — accidentally wiped out weeks of work. Unable to recapture what they'd already recorded, Becker and Fagen ultimately abandoned the song.

The duo were also slowed by a snafu of their own design when, after complaining to engineer Roger Nichols that they wished they could simply program a machine to give them the drum tracks they really wanted, Nichols turned around and invented a drum machine they christened "Wendel."

"One of us said something like 'It's too bad that we can't get a machine to play the beat we want, with full-frequency drum sounds, and to be able to move the snare drum and kick drum around independently,'" recalled Fagen. "Roger replied 'I can do that.' This was back in 1978 or something, so we said 'You can do that?' To which he said 'Yes, all I need is $150,000.' So we gave him the money out of our recording budget, and six weeks later he came in with this machine."

Wendel became a fairly integral part of Gaucho, ultimately being awarded a platinum record for "his" efforts on the album, but programming technology was so primitive at the time that getting sounds of the machine was almost more trouble than it was worth. Noting that Nichols' invention relied on a computer keyboard, Fagen said, "He had to type all these bytes out, huge lists of numbers, which took him 20 minutes, and at the end he would hit Return, and we heard this one snare beat. It took so long."

Listen to 'Time Out of Mind'

Out of all these trying circumstances, a sort of song suite slowly coalesced — one whose arrangements still bore Becker and Fagen's distinctly jazzy imprint while drifting away from complex chords and placing more of an emphasis on the sort of arid, lockstep grooves enabled by Wendel (not to mention an army of session drummers that included Bernard Purdie and Jeff Porcaro). Lyrically, Steely Dan had always tended toward the skeevy, but the Gaucho tracks took a darker turn, presenting pictures of troubled, often deluded protagonists drifting through the post-Sexual Revolution bar scene in a drugged-out haze.

Not exactly the stuff of Top 40 programmers' dreams, then — but that had pretty much always been the case with Steely Dan, and they'd still managed to do fairly well for themselves on the radio. That continued with Gaucho, which spun off a pair of hit singles: "Hey Nineteen," a mid-tempo number whose bitingly funny lyrics about an aging barfly half-heartedly fending off the perceived advances of a younger woman were offset by the deceptively sunny slope of its easy-listening arrangement, and "Time Out of Mind," a poppy ode to heroin featuring the briefest bit of guest guitar from Mark Knopfler of Dire Straits.

Just to get Gaucho into stores, Becker and Fagen had triumphed over tremendous adversity, but after its eventual Top 10 success, they were burned out rather than triumphant. In fact, the record's release marked the last time they'd put out a collection of new studio recordings under the Steely Dan banner for two decades. While they'd continue to work together on their respective solo projects during the '80s and '90s — and they mounted a surprise return to the road with the first of many occasional Dan tours in 1993 — Gaucho took the band as far as it could go for a good many years.

"Working together as long as we did, Donald and I followed a certain line of thinking to its logical conclusion, and then perhaps slightly beyond," Becker told Mojo. "That was what we realized when we'd finished Gaucho: It was not as much fun. ... It wasn't fun at all, really."

See Steely Dan Among the Top 200 '70s Rock Songs

More From Ultimate Classic Rock