How Steely Dan Took It To the Next Level With ‘Aja’

Steely Dan's sixth studio album arrived in September 1977 as the artistic pinnacle of the '70s jazz-rock movement.

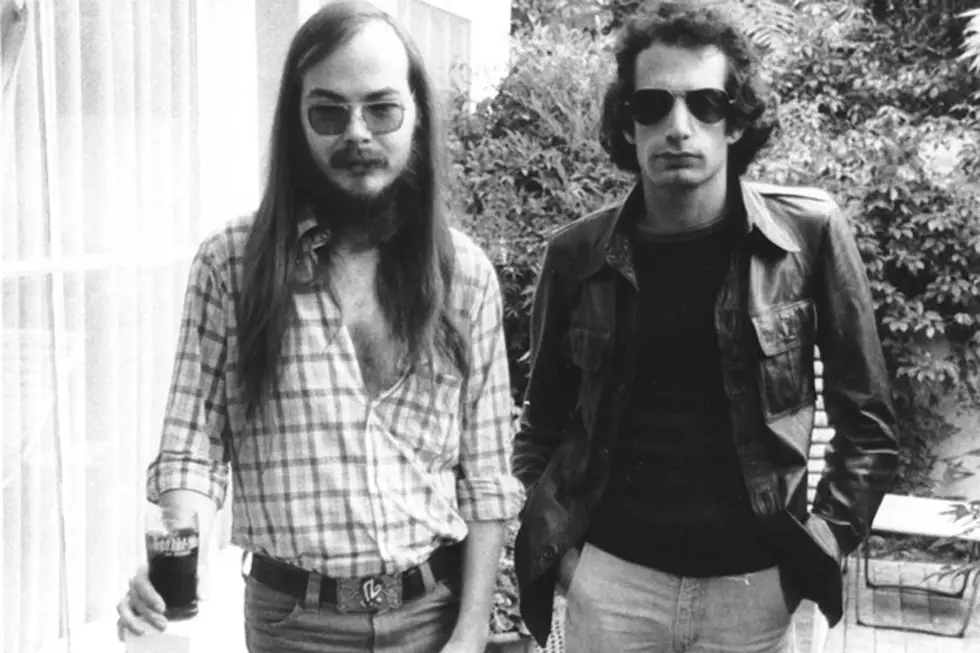

Their 1976 album Royal Scam had been a solid, guitar-centric album which nonetheless met a lukewarm critical response. Studio mavericks Donald Fagen and Walter Becker set to work on a follow-up in January of the following year, recording over a six month period in various state-of-the-art studios across New York and L.A.

Aja became Steely Dan's highest-selling album, reaching No. 3 on the American charts. More importantly, it remains their most fully realized collection of songs.

At this point in their careers, Fagen and Becker had transformed Steely Dan from a legitimate recording and touring band into a songwriting partnership. They wrote the material themselves (with production assistance from Gary Katz), aided by a jaw-dropping slew of ace session players. They'd become sonic perfectionists, scrutinizing every overdub until every note was irrevocably in place.

On the pristinely recorded and performed Aja, however, their attention to detail was taken to bold new heights. Meanwhile, the personnel read like a who's who '70s jazz/R&B session musicians: drummers like Steve Gadd (on the explosive title track) and Bernard Perdie (whose infamous 'Purdie shuffle' perked up the funky "Home at Last"), longtime bassist Chuck Rainey, vocalist Michael McDonald, and sax legend Wayne Shorter (whose effortless solo on "Aja" ranks among the band's most epic moments).

Eventually, Fagen and Becker's obsession with getting the absolute best performance transcended perfectionism, landing somewhere in the neighborhood of Stalin-esque. As legend has it, the duo filtered through dozens of failed guitar solos from outside musicians on the infectious "Peg," before eventually settling on Jay Graydon's Polynesian-influenced take.

"That's one of the best tracks I ever played on," drummer Rick Marotta said in the 2000 documentary Classic Albums: Aja. "As far as drums were going at that time, if you had a club in your left hand and a club in your right hand and clubs for feet, you could play. I just opened my hi-hat a hair, every couple of beats with what I was playing on my right hand on the hi-hat, and it created this little sound. I had done that but never ever heard it on a record I'd done because [with the] engineers and sounds at the time, it was a nuance, and those things didn't exist."

Reflecting on the duo's relentless quest for the perfect combination of players, Marotta noted: "It wasn't like they played musical chairs with the guys in the band; they played musical bands! Whole bands would go, and a whole incredible other band would come in!"

A triumph of engineering, Aja rightly won the 1978 Grammy for Best Engineered Non-Classical Recording. The surfaces sparkle with sophistication, capturing every performance in full clarity – as if you're hearing the music from inside the amps and drum heads. But Aja is also a masterpiece of performances, and of the nitty-gritty details (like Rainey's slap-bass harmonics on "Peg" or the subtle, steady climb of horns and synths on "Black Cow").

In addition to "Peg," Aja also spawned such classic radio singles as "Deacon Blues." "Walter and I had been working on that song at a house in Malibu," Fagen later told Rolling Stone "I played him that line, and he said, 'You mean it's like, 'They call these cracker assholes this grandiose name like the Crimson Tide, and I'm this loser, so they call me this other grandiose name, Deacon Blues?' and I said, 'Yeah!' He said, 'Cool, let's finish it.'"

"Josie" continues the pristine goodness of this album. A song about a girl who turns all the guys heads, Fagen and Becker the exact same thing musically to the listener every time. "By the time we did Aja," Fagen noted in the Classic Albums documentary, "we'd figured out sort of what it was we sort of wanted to do, musically."

Becker added: "I think the Aja album has so much great playing in terms of what we were trying to do with combining session players and soloists, and so on, to produce these little ideal tracks for our songs. That was sort of the best, most consistent, and most successful example of that."

Steely Dan Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock