The Night Patti Smith Performed on ‘Saturday Night Live’

Patti Smith has always felt underrated as a poet, author and songwriter – despite glimmers of what could be construed as fame that put her work in front of a larger audience.

For those who were lucky enough to witness it, an April 1976 performance on Saturday Night Live with the Patti Smith Group was certainly one of those moments. Caryn Rose, author of Why Patti Smith Matters, was one of them.

She paints a picture of Smith as a true artist, in that Smith creates without regard for a potential audience. During the the Patti Smith Group's early days that on the road, for instance, she would issue a challenge: "Next time we come to town, don't even come to see us. Be at another club playing yourself."

Why Patti Smith Matters digs deep into every corner of her career, touching on moments that are known and many that are less known. In this exclusive excerpt from the book, Rose takes us back to that life-changing evening spent in front of the television.

It was almost midnight on a Saturday night in 1976 and I was sitting on the floor of my family’s TV room, as close to the set as I could get without being chided for being too close, but close enough to allow for sufficient volume without being yelled at to turn it down. I was watching NBC’s Saturday Night Live.

I was a fairly sheltered, suburban 12-year-old, so I didn’t get most of the sketches, but my primary reason for watching was the musical acts. I do not remember ever not having insomnia and staying up later than I should, reading or listening to the radio; my mother also liked to stay up late, smoking, reading magazines and watching old movies, and I would often sit up with her on weekends.

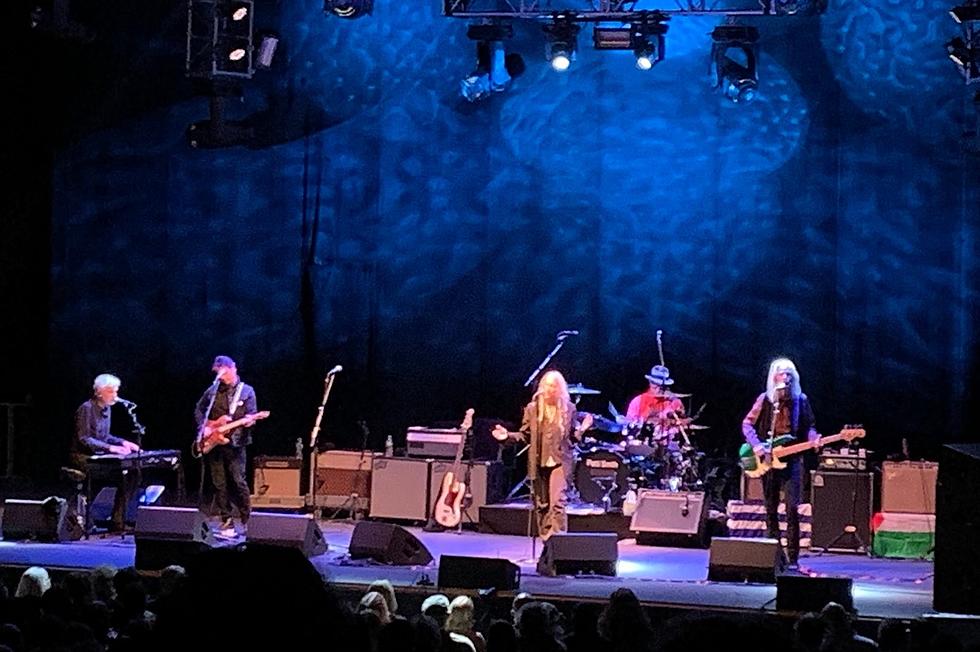

This night, however, the television was mine. The episode was hosted by White House press secretary Ron Nessen and featured filmed cameos of President Gerald Ford. And then, there it was, on the screen: PATTI SMITH GROUP. I don’t know what I was expecting, but it floored me. There was a woman onstage and she was out front and it was her band: the musicians were supporting her.

She was wearing a white button-down shirt just like on the cover of Horses and an actual tie around her neck. Her hair was perfect, a jagged, black-hennaed mess. She didn’t move around much — the stage was so small that Richard Sohl wasn’t in any of the shots beyond the intro chords to “Gloria” — but she was like one of those toys you would wind up and then let go and watch it spin. At the end of the song, before the last chorus, she was breathing hard, but she was smiling, she knew she done good. She murmured at the end “Happy Easter, CBGB.”

I knew what CBGB was because when my father would go into the city for business, he would come back with a record I had asked for or a magazine that had someone holding a guitar on the cover. One day he came home with Rock Scene. “I thought this was one of your bands,” he said, pointing at David Bowie or Keith Richards.

That Monday, Saturday Night Live was a topic of conversation at school like it always was. Except that I did not completely understand that being a fan of this band, a band that no one else had written on their blue canvas three-ring notebook except me, meant that I was now guilty by association. I was already “different”: I didn’t drink, smoke, or take drugs. Boys did not know I was alive. I liked to read and was always either juggling a stack of books or trying to hide behind one so I wouldn’t be noticed. I didn’t have many friends, and the friends I did have weren’t music fans, at least not like I was. The other kids who were music fans wore Aerosmith T-shirts or carried around Jethro Tull or Lynyrd Skynyrd albums. I knew all that music because that was what you heard on FM radio, but it didn’t mean that I liked it. I tried.

But this day was different because Patti had dared to step into their world. What fascinated and drew me in repelled others, and to them, their aversion was my fault. Patti hadn’t gone onstage to be consumed; she didn’t smile; she wasn’t wearing a dress or even fancy stage clothes. I knew that she was Different, but she was just on national television. “Les ... be ... friends!” one of the popular kids yelled as I walked by; everyone else snickered or pretended to, so they wouldn’t be a target. My head was down and I was looking at the floor, so I didn’t see when someone walked by and bumped into me so I crashed into a locker.

This was a town 45 minutes away from New York City by train, but the message was clear: people like her — people like you who like her — are not welcome here. (As though I hadn’t figured that out already.) I think of an article about Patti in Mademoiselle in 1975, where she referred to the interview as “a revenge for bad skin,” revenge on anyone back then who thought or called her weird. In that same interview, she described the people she left behind in South Jersey: “They don’t realize that all you have to do is get on the fucking train and you’re in New York. In New York, all you have to do is get on a plane and you’re in Paris.”

The town my family lived in was exponentially closer to the city than Patti’s town and was located in one of the richest counties in the country at the time, and yet somehow I was also surrounded by people with similarly small vistas. But here she was: tangible proof that you could survive, you could get out, and you could flourish.

“And I will travel light / oh, watch me now,” she declared in “Piss Factory,” and she was right.

Top 100 Classic Rock Artists

More From Ultimate Classic Rock