Chickenfoot Drummer Kenny Aronoff Talks About Playing with Some of Rock’s Biggest Names

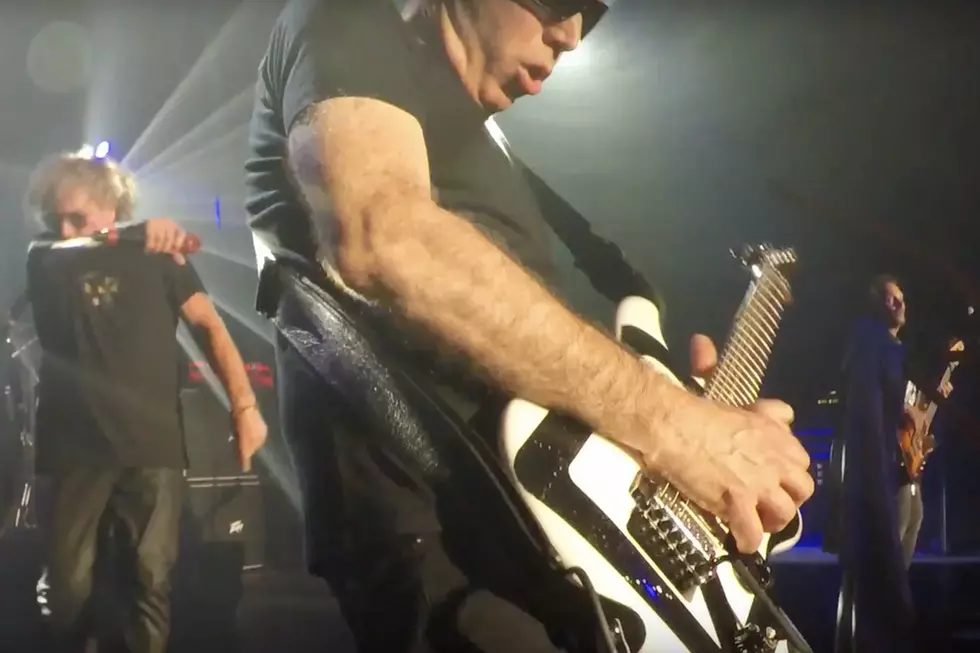

For this writer, seeing legendary drummer Kenny Aronoff (John Mellencamp, John Fogerty, Smashing Pumpkins, Bob Seger, etc.) live for the first time with Chickenfoot in 2011 -- at a special club show at the Metro in Chicago, no less -- was an experience that personally was on par with seeing bassist Nathan East (to use one example) playing with Eric Clapton in the ‘90s.

As Chickenfoot launches a new leg of U.S. tour dates, the opportunity arose to talk with Aronoff and we couldn’t resist digging into several topics.

Of course we had to ask him if he’d be up for playing the Incredible Hulk in a classic rock version of ‘The Avengers.’

With the Avengers movie in theaters, we’re currently running a poll to determine what rockers might be able to play each superhero in a classic rock version of the movie. Your name was one of several that popped up as a possibility for the Incredible Hulk.

I know! Dude! I just got something on Google Alerts and I was like ‘this is f--king awesome!’ I love it! I f--king love it! That is so cool. It just means that I’m muscular and in shape!

Well, you’re currently losing to Meat Loaf.

What? [Laughs] Okay, after his name was mentioned....Meat Loaf would win for sure with the craziness of the Hulk! You know what? What they should do is meld him and me together. Because his physique...well, he’s not ripped, but he’s got the attitude and that kind of demeanor of the Hulk when he gets green.

That was one thing I wanted to point out, is that the other people on the list - Tom Petty, Axl Rose and Meat Loaf - were put on there for temper issues.

Tom Petty? [Laughs] The Hulk? He’s more like the spiritual being!

You’re the only one who wasn’t nominated on that criteria. We just thought you looked bad ass enough to pull it off. That says a lot, I think.

Yeah, I like the fact that...it’s probably my whole physical demeanor, because I’m not very big, I’m just cut and muscular. Let me think....Axl Rose, wow, for temper for sure, he wins and for craziness. He’s up there...and this is not in a bad way...this is all being in comparison to me and from what I’ve heard.

Meat Loaf, I’ve worked with him a bunch, on three of his records. He’s like....I love that guy. And I think it should be me and him melded together, my muscular cut with his persona and presence. You know, that’s a tough one, man, because he could be the Incredible Hulk in a certain period of time when maybe he was just watching a lot of TV and eating ice cream.

“Persona.” That’s a good word, because Meat Loaf has a definite presence.

Oh my God. Well, I could tell you stories, but I’d be scared it would get out in the press. I’ve got some good ones, holy shi-t.

You’ve played with enough people that I think you have good stories about quite a few people.

Mmmmmm. Dude, I could write the book, but I’d better have a lot of money ready for the lawsuits.

With the brief gap in dates recently for Chickenfoot, what have you been up to?

Oh my God, some incredible things. Alright, this is just in the last month. I did three weeks in Australia with John Fogerty, which is amazing. In one week, we alternated nights, one night we’d do one of his most famous records, the ‘Cosmo’s Factory’ record in its entirety and the next night we’d do ‘Green River’ in its entirety.

Of course we’d add at least another hour of music, if not maybe an hour and half of music - he’s got more hits than anybody in the world. I managed to do a few drum clinics while I was out there, where I do my own two and half hour show. And then I came home and closed on a house. People say that’s one of the most stressful things you can do in life, well, I don’t think about things like that. ‘Eh, just squeeze it in,’ you know I threw in a root canal on one day, closed on a house the same day and it’s like whatever, but it is pretty stressful. It’s just a big pain in the ass.

If you’re somebody like me who’s got such a busy schedule, you just want to snap your fingers and make the transition. It’s not that easy. Nowadays, you can have enough money to buy the house in cash, but if you’re going to take any kind of loan at all, it’s like having five colonoscopies without anesthesia because of the banking situation.

So then I went down to Austin, this was within a week of coming home from Australia and did this amazing Johnny Cash tribute with Don Was as the musical director. It was Buddy Miller on guitar, Greg Leisz on every other instrument, Don Was on bass and me on drums. We played for...the list is ridiculous...we played for everybody. It was a Johnny Cash tribute that was being filmed for DVD and recorded at the new Austin City Limits location. But you know, like Brandi Carlile - she was amazing...kicked ass! She started the whole show with ‘Folsom Prison Blues.’

Have you ever heard of Carolina Chocolate Drops?

Oh yeah.

Unbelievable. Holy sh-t. Then this kid, this new guy, Andy Grammer, have you heard of him?

Sure have.

You won’t believe this guy - we did ‘Get Rhythm.’ We didn’t play these songs in most cases like the recordings, we mixed it up. Andy Grammer, we did ‘Get Rhythm,’ but we did it more like a New Orleans funky [kind of thing]. [Aronoff continues to read names off the list of participants]

Kris Kristofferson, Shooter Jennings. Lucinda Williams to me was....she did a song called ‘Hurt’ that just slayed everybody, it was deep man. Amy Lee from Evanescense, Shelby Lynne, who’s ridiculous, Ronnie Dunn, from Brooks and Dunn. You hear these guys, but when he came out and sang ‘Ring of Fire,’ that voice, it’s unbelievable. Pat Monahan from Train, he’s amazing, I just did something with him. Rhett Miller, who tore it up, Willie Nelson.

And then they did a thing where they did the Highwaymen thing, where we did a song called ‘The Highwaymen.’ Of course, Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings are dead, so Shooter Jennings did his dad’s part and Jamey Johnson [was also] on it. It was amazing.

The pressure for me in a situation like that, because I do the [the annual Kennedy Center Honors event] every year. The pressure about that is literally, the people are coming in, they’re holding the doors and we’re still rehearsing about 10 minutes before the people are coming in. And I write everything out, so I have to write out not only the tempos, who I’m counting off to, what the count off is, every beat.

Because we’d never run the show in its entirety in sequence and you’re looking at titles and going like ‘sh-t, I can’t remember how that song goes!’ And I’ve got to count off to come in and usually the drums are doing a pickup. You’ve got to get the feel right, the whole vibe right and then the endings. You have to know every stop and how it will end and these artists have maybe played the song with us twice, that’s it, the day of the show or the day before.

And if they go off into another place, it really is up to me to direct us, where we’re going, so there’s a lot of pressure on the drum chair. If I couldn’t read and write music, it would be hopeless, because there’s just too much to remember. You’re rehearsing literally right up until they let the people in and then you have one hour and then you have to do the show and they’re filming it and recording it! But I love that stuff, it’s really exciting.

I did that, flew home, moved into the house and then started taking on this incredible project. It’s a Jimi Hendrix movie and Andre 3000 from Outkast is playing Jimi Hendrix.

Nice!

Here’s the challenge: So the legendary Waddy Wachtel is the guitar player and the legendary Lee Sklar is on bass. We basically had to become the Jimi Hendrix Experience - which is ridiculous. First of all, you’re talking about, how are we going to get those sounds, how are we going to get the feel....I honestly believe that you have to have grown up in that time, you have to have lived through that time to understand and feel it.

It’s not just playing the notes, you have to understand and have felt the whole cultural movement in the ‘60s. Because the music in general, is reflecting a personality of the economic, political, cultural times of the world and then more specifically, America. That whole hippie movement, the whole creative movement that was going on and I was part of it as a kid. But then when Jimi came out, it really f--ked with my head in a good way, because it made me mature.

I was listening to nice music, like the Beatles and whatever was on the radio. When ‘Purple Haze’ came out and hit the radio, it was a serious tone, it was like ‘holy f--k.’ This was about drugs, sex, a vibe, you know, somebody who came from Mars. It was a positive thing - it wasn’t dark, but it was scary. I remember listening to it in the dark and smoking my pot and going ‘what the f--k? I want to be this guy, I want to be in this band, oh man, I want to live this world,’ I get it!

So suddenly, like eight billion years later, being asked to record ‘Hey Joe’ from the ‘Are You Experienced’ record, I wrote it out note for note, listened to it over and over again, watched anything I could see on Youtube and I’d seen Hendrix live as a 13 year old boy. So I remember having a vision of Mitch Mitchell and the way he looked and the way he played, because he was a jazz drummer, which was how I started out. So it was basically method acting, the way these actors really get into their roles and they become the person.

So basically, that’s what I was trying to do for a week, on top of moving and all of this other stuff. [I was also doing] some other sessions for other people and trying to get ready for Chickenfoot.

Besides 'Hey Joe,' which you mentioned, what other songs did you tackle for the Hendrix thing?

We were in the studio for two days and Andre was there with us and we recorded ‘Wild Thing’ from the Monterey Festival in California, which is historical, ‘Killing Floor.’.....we did a scene where Jimi goes to England for one week. He goes there and all of the sudden everybody - Zeppelin, The Who, Cream, everybody came down to see ‘who is this guy?’ I think it started where he got on stage with Cream and his manager pushed him up there and said ‘c’mon, show ‘em what you got.’ He goes up there and does this ‘Killing Floor’ song, wicked fast and he says to them something like ‘do you guys know the song ‘Killing Floor’ and they were stumped.’

It’s really, really fast. So [now] I had to be Ginger Baker. Waddy even said ‘don’t play like Mitch, you’ve got to play like Ginger.’ Because remember, Jimi is sitting in with Cream and these guys are trying to keep up with him, because these guys are like ‘who the f--k are you?’ So you’ve got to have an attitude like ‘hey, little f--ker from the USA, I can keep up with you.’ So stylistically, I’ve got to be Ginger Baker, which is a whole another guy.

I mean, I flew to England to see the [Cream] reunion when they played in London once, because I’m such a massive fan. That was an intense two days. We did ‘Wild Thing,’ ‘Hey Joe,’ ‘Bleeding Heart,’ ‘ Cat’s Squirrel,’ which is a [another] recording of us being Cream and then we did a couple of other things and it was amazing.

So Jimi, you’re blown away by what he’s doing as an artist. When you ended up doing your own thing, how did you wind up being a drummer and not a guitar player?

Well, drums came first. I was a drummer at 10 years old and I heard Jimi when I was 13. When I said ‘be Jimi,’ I just meant be his whole spirit as a drummer. Guitar, nah....I can’t play guitar - I suck at it! It was just the whole spirit, that whole rebellious [feeling] in a nice way, like a peace and love [kind of] rebellious. It was rebellion, it was ‘act how you want, feel your feelings, dress how you feel.’

I mean, this is post-World War II, this wasn’t that far after World War II, so think about it, people weren’t exactly like [receptive to the idea of rebellion]. ‘Rebel, are you f--king kidding me? We’re lucky we’re not marching to Hitler’s music. We almost got taken over.’ When my dad was a bomber, he was one of the guys that navigated the big bombers to help end the war. So all of the sudden we’re growing our hair and rebelling?

He’s looking at us like ‘dude, we’re lucky that we have a house, we’re lucky that we have money.’ A lot of people his age that fought the war were thinking ‘what? what are you f--kers doing?’

Drumming was a natural thing for me, because I have this theory that when you’re a kid, you’re just trying to be happy and I had super, super high energy as you can tell and I was naturally drawn to sports - anything that had physical activity - and I loved music and I got drawn to the energy of drumming.

I grew up in a very small town in New England, Stockbridge, Massachusetts, an artsy little town, and they had the marching band come in on Memorial Day to honor the veterans, of all of the wars. When that drumline would start, I would go apesh-t. I was a little kid on a little one speed bike with little streamers through the thing and I’d ride around the drumline just going ‘Wow!’

You know, I never took any formal drumset lessons, because there was nobody teaching there. They’d give you a pad and you’d learn how to read and hold the sticks, but I bought it, I was gardening at 50 cents an hour like a little kid, saved up my money and got a snare drum and then I got a cymbal and actually got a kick drum for my birthday and a floor tom for Christmas and I was in a band when I was 11.

It was just a fun thing to do. I had started studying with the percussionist from the Boston Symphony Orchestra when I was 16, because they were up there in the Berkshires where I grew up. The Boston Symphony Orchestra, their summer home was like three miles from my house. There was some kid in town that was getting better than me and he was taking lessons from him. So I went to take lessons from him and that was like taking lessons from one of the toughest football coaches, just real Marine style.

There was no joking around, this is serious business. He basically ripped me a new asshole. He started me back on the pad and he gave me drumset exercises, but it was mostly classical. By the time I was 18 and it was time to go to college, I decided I would do music and I was kind of behind in the classical world, because in high school, I was playing sports and wasn’t involved in the high school marching band or orchestra. I had my own band - why would I want to play stupid symphony music when I was playing Hendrix, Cream and real rock and roll.

But then, when it was time to go to college, I was lacking some of that formal training. So I was practicing eight or nine hours a day, the summer before I went to college, on mallets, timpani, marimba, snare drum, music theory, all of that stuff. Yeah, I got into college, but I spent one year trying to catch up to everybody else. And then I went on and did four more years of hardcore orchestral training at Indiana University.

My first year was at the University of Massachusetts, which didn’t have the prestige or the honors of the school like Indiana University, which was one of the top three schools in the country and the largest music school in the world. You know, five orchestras, five jazz bands, every semester of school, I had to play a full blown opera in an opera hall the size of the New York Met. It was hardcore. And I had a teacher there that was no f--king around - you don’t come prepared, he can wash you out. He’d literally wash you out.

I saw guys leave the school, they couldn’t handle it - he’d break you. That’s where I got a lot of discipline, and all of that sports training, playing on teams and working with these intense teachers in classical music gave me massive discipline and taught me the skills to be able to read and write music. But I was self taught originally, so I have that street kind of sense of rawness and I’m not completely slick, you know what I mean?

Yeah.

I’m more raw than slick, but I have the tools to be very, very precise.

As you start this next leg of touring, Chickenfoot has been rehearsing. Were there any items that you guys wanted to tackle as a group and improve upon going into this next run?

No, I mean, we’re working off of two albums and we only rehearsed for two days. It’s a band, it really is, it’s that level. Everybody probably reviews stuff, I mean, I did, definitely I had to. You review the stuff that we’re doing. The set that we put together on the promo tour in Europe and the promo tour in the USA, that’s our starting point.

We made a few arrangement changes, but the cool thing about this band is that the level of musicianship is so high and everybody’s been in so many bands that we’re starting at such a high experienced level that there’s a lot of stuff that you don’t have to discuss. It’s like if you took a bunch of NFL players and put them together, they’re already starting with a lot of experience, so it’s just a matter of making it gel. And it gels so well, personality wise and musically.

And I think maybe that’s what Chad [Chickenfoot drummer Chad Smith] was thinking when he picked me. He picked me personally, he kept telling them this is the guy you should get to replace me while I’m out with the Chili Peppers. And it’s worked - he’s right. It was just the right combination of people.

What are the songs that have been evolving during this touring run?

You know, the songs we jam on like ‘Down The Drain.’ The biggest evolving is when Joe [Satriani] is doing a solo and I’m playing off of him and pushing him and listening to him and trying to stretch him. We’re pushing each other.

So ‘Down The Drain’ and even at the end of ‘Future In The Past,’ where we really jam, it’s like ‘get ready, man.’ Parts start developing and it’s always evolving - there is a structure in that we know where we’re headed, but while we’re soloing, it could go anywhere. ‘Turning Left,’ we have sections in there - it starts off with me and Michael [Anthony] playing, just the two of us, it’s like kind of a bass/drum solo - that kind of has evolved.

I had the chance to see the Chicago date of the ‘Road Test’ tour and it seems to me like Chickenfoot might be one of the heavier projects you’ve played with. Would that be an accurate assessment?

Yeah, although I’ll tell you, I don’t play any lighter with Fogerty. Holy sh-t, that guy demands power and edge. But this band, as far as the improvising and the stretching out on stage, probably the last band I stretched out and jammed like this was the Smashing Pumpkins, which was 1998.

That’s interesting to hear, because I would have thought that band would have had a lot of structure.

Well, [Pumpkins mastermind Billy Corgan] is a controlling person, but he wanted a lot of improvising too. And he actually allowed me to create a lot of....I mean, I put in some parts. I came up with a whole direction for ‘Bullet With Butterfly Wings,’ because Marilyn Manson had come out with ‘The Beautiful People’ and I was thinking of doing it more like that. And Billy was always listening to see what somebody could bring to the table. So yeah, there was some serious improvising going on at times....at times. But let me say, I grew up playing in fusion bands, jazz bands, so this thing was totally familiar to me and I played in different bands all of the time that never became famous that we used to seriously jam.

Like the guitar player from Melissa Etheridge, Philip Sayce, who is a bad motherf--ker. We played in clubs the last 10 years and it’s really stretching out. So this sort of playing is so natural to me. I don’t know if it seemed that way, but it’s structure with improvising, it’s totally what I grew up doing. I love the power of it all, because it’s rock and roll. It reminds me of being in Led Zeppelin and Van Halen, all combined.

That is an excellent comparison, because that’s exactly what I got out of seeing you live with Chickenfoot. I’ve heard your drumming on so many albums, but this was my first time getting a chance to see it live. I guess I had a certain expectation of what I was going to see, but it went even beyond that. Which I guess is a good thing as a band, when you’re looking to introduce a new album, you do want the live show to carry it to the next level.

Are you going to get out to any of these upcoming shows?

I’m trying to line it up on my concert calendar as we speak!

You saw the Metro show. I love Chicago. That’s where I played my first show with the Pumpkins.

Oh wow, nice!

Check this out, I’m about to go on stage and my 10-year-old son, I’m walking on and he says ‘you should wear these glasses’ and they were these goggle glasses. I had a black shirt with a yellow stripe down it and he said ‘it matches your shirt.’ He was 10 years old, he gave them to me and I went on and the person who reviewed the show talks more about my glasses than my playing and I went ‘well, that’s that’ and that’s why I wear glasses. That started the whole glasses thing. Is that crazy?

That’s crazy.

And then I went ‘this is stupid, I gotta stop wearing this sh-t,’ I started taking them off and people started saying ‘what the f--k, where’s your glasses - we came to see what you were going to where.’ And I went ‘oh my God, don’t fight it.’ You know, when you’re a drummer, you can only see from the waist up, so if you’ve got something that’s working for you, stay with it.

It definitely doesn’t hurt the vibe of the intensity that you give off and apparently, it makes you very Hulk-like.

Dude. I am so flattered that somebody would even put me in that list. That’s cool.

So since we’re talking about Chicago, ‘Last Temptation,’ one of my favorite tracks from the new album seems like it dropped out of the setlist after that show. What happened there?

Oh man! That’s exactly what we’re saying. In rehearsal, Michael and I said...I mean, I love, that’s one of my favorite songs on the album. I was just reviewing it last night with the hopes that we’re going to do it. I’m going to start making us do it in rehearsal. I want that song back in the set. I love it. At least rotate it. I think it would be cool to have a set and one night do that and another night do whatever it replaces.

When I talked to Michael, I expressed how difficult it must have been to sequence the new album, because there are plenty of tracks that would have made good leadoff songs and on the album, those duties fall to ‘Last Temptation.’ But there’s a lot of power players like that on this record.....

I know. That’s a great track. It’s got such cool sections to it and good energy, you know? I love that song.

Well that song and ‘Up Next’ are probably two of my favorite songs in that category on the new album.

Wow, yeah, ‘Up Next.’ [mimics instrumental section] That gives me chills, when I listen to it or practice to the stuff and I hear Sammy’s voice with all of those players, it’s magical. Joe Satriani just completely slays me. All of them do. It just blows my mind. I’m sitting there and I’m such a huge fan of Joe Satriani now as a person and as a player, he’s just brilliant, he’s Buddha.

And then Sammy’s voice is one of the greatest rock and roll voices ever and his personality is larger than life. He is one positive motherf--ker and happy and he is living life. He’s got the right attitude. F--k the Cabo tequila - he should bottle himself somehow. Maybe that’s what he was trying to do with all of this liquor, but he should bottle [himself] because he’s got such good energy.

Michael, I have never heard...he’s such a natural at whatever he does. He’s always in time, his singing, it kills me. When we went and did Sammy’s birthday party in Cabo, I was in the audience watching them play with the Cabo Wabo band and I’ve never heard the vocals from a distance so it just cuts through the PA and his blend with Sammy, it doesn’t get any better. It’s a superband, man, I hate to use the word, but it’s a superhero bands. We’re the Avengers! I mean, am I right or what?

Definitely. But so many of these “supergroup” projects seem like something that would work great, but even with all of the best players, sometimes the songs aren’t there. And the whole package definitely is in place with this project.

You’re right man. Just because you put a bunch of guys together, I would have thought the same thing. ‘Oh yeah, whatever,’ but it is magical, it is. Usually when I’m in a band, the people who review shows, it usually goes to the lead guy and then it usually goes to me. With Mellencamp, it was John, John and then it was like Kenny Aronoff, Kenny Aronoff, Kenny Aronoff, [and it was like that] in almost every band.

In this band, it’s like, I’m the last guy, because all of these guys are so f--king bad ass. Sammy is one of the greatest frontmen and then they go to Joe, who is unbelievable and then they talk about Michael. I’m so glad they’re giving Michael all of this attention that he deserves. Because with Van Halen, he was not talked about as much. They’re talking about Michael a lot as if he was right up there.

They’re saying it was good to see Michael up front, it’s good to hear his playing, it’s good to hear him sing. He deserves all of that attention. And then they get to me....what I’m saying is that there are so many great players...usually I was the next guy, I was the player they talk about after the leader. Not so in this band. I love it - it’s like being on a Super Bowl team or something.

You first got the chance to play with Joe in Mick Jagger’s band and he’s said that gig was hard for him critically, because he was standing in the shadows of Keith Richards. What was the experience of playing with Mick like for you?

Okay, here’s what happened. I walk in and I’m like pumped, Mick Jagger, holy f--k. I set the drums up and there’s Joe with a big afro and I just started playing, I don’t know what the f--k, I just started playing some funky groove and Joe’s looking at me like ‘wow, oh okay,’ not like let’s talk about what we’re going to do, I just start playing.

Mick starts dancing, doing like a chicken dance, feeling it and I won the audition. But they kept changing the dates, I was with Mellencamp and my dates didn’t work out, I didn’t get to do it. But I did get to record on two Mick Jagger albums and hang with him. There was one time we were eating dinner together - this would be in my book. We’re eating after recording, sitting right next to each other, because I’m the one overdubbing drums.

He goes ‘hey, can you stay and record tomorrow?’ He liked my playing and asked me quietly ‘can you record tomorrow’ and I went ‘I can’t, I’m flying to Italy to tour with one of the biggest artists there, Vasco Rossi.’ We’re talking like 120 thousand people came to the first gig. I couldn’t do it. I had to say no to Mick Jagger, because I had to fly to f--king Europe. And the wild thing about this, is I found out later....he never said anything to me, he just said ‘oh, okay.’

But the Stones were supposed to open up for Vasco Rossi a long, long time ago, but for some reason, it didn’t work out. So he knew who Vasco was. But yeah, I didn’t get to do that tour, so I don’t know what it would have been like. But I always felt like I understood the Stones so well from being with Mellencamp, because that’s what we emulated so much, even though we didn’t sound like the Stones, that’s who we paid attention to, all of the time.

With Chickenfoot, besides Joe, what’s your history with the rest of the guys?

Well, the first time I met Hagar was a famous time. We were at the first Farm Aid together. I played with like nine bands. I was sitting in with everybody. And that was the time he went on stage and brought out Eddie and announced to the world that ‘I’m playing with this guy’ and he said ‘f--k the farmer’ or whatever he said and it went off the air. I was there and I went ‘oh no! what the f--k did that guy just do?’

And then another time I met him, we were doing a festival in JFK, probably a couple of years later. It was huge, it was like Journey, Sammy Hagar, Bryan Adams, Mellencamp and somebody else. Sammy came on stage and he’s just friendly. He comes into people’s dressing rooms, saying hi to all of us, so I met him. And then another time, I was doing a Meat Loaf record and he walked in and he said ‘hey Aronoff, don’t f--k up now!’ He was watching me record....I think that might have been it.

So I knew him like that. With Michael, I’ve met him a couple of times. The last time I met him, we both did Rock and Roll Fantasy Camp. I came in one day and we were both judging one of the bands and we were both together, walking into the room. It was Kip Winger’s band.

Another time, I met him and we were both staying in the same hotel in Boston at the Ritz. We were hanging out and we were both wearing the same necklace. A guy, a friend of ours, made this necklace for three people - me, Michael and Matt Sorum and I went ‘oh my God, you’ve got that same necklace!’ So it was that kind of thing, that’s about it.

The era in which you were making records with John Mellencamp seems like it was a really fun time to be making music and so open for creative possibilities. You came into the band at a time that he was already doing some exciting things musically and ‘I Need A Lover,’ which was recorded prior to you joining, sticks out as one that really pushed the boundaries of what was on rock radio at the time. Hearing songs like that, what was on your mind as you began working with John?

Well, what happened was, I started out wanting to be in the Beatles or Jimi Hendrix, I wanted to be in a rock band. I did that, but then I got into this heavy classical thing, because I thought...there was no blueprint on how you make it in rock and roll. And I was living in this small town of three thousand, so I didn’t have anybody to [be] a role model. I wasn’t living in New York City or L.A., where there was a whole scene.

So I pursued the classical thing thinking that you get into an orchestra, you get paid, you make a living, blah blah blah. So I get done with school and I spend a year living at my parents’ in Massachusetts, practicing nine hours a day, studying with two drumset teachers. I turned down two orchestral gigs - one to be in the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra in Israel and another to be in a symphony orchestra in Ecuador and I turned them down. I was in shock...what? You spent seven years devoting yourself to becoming a great orchestral player and you turned it down.

I decided I’d rather be playing in clubs, playing rock and roll or fusion for fifty bucks a night than to wear a tuxedo. I moved to Indiana and formed a band, and spent three years being in a band. It was a fusion band and a rock band and living in a band house and I realized I’d better move to New York or L.A.

And then I’d heard about this Johnny Cougar guy and I wasn’t a big fan because it was more commercial than I had wanted. But then I was about to leave....literally, I’d quit my band and in two weeks I was going to leave for the East Coast and I hear that he’s looking for a drummer. And then I started examining it more. I listened to the ‘John Cougar’ record, ‘I Need A Lover,’ etc. And then I started seeing him on MTV and then I’d hear him on the radio and I’m like ‘wait a minute dude, this is what you always wanted to do, wait a minute - get your head out of your ass. This is more of what you grew up listening to!’

You see, when you’re younger, you’re always thinking more notes, more notes and by playing simple, basically I became the drummer that I used to make fun of. I became that guy - I’ve become an expert of what I used to make fun of. I mean, there’s a lesson right there in life. What happened was, suddenly I came full circle and I realized ‘I want to be on tour, I want to be on the planes and the tour buses, I want to do the TV, I want to make records.’ I went ‘holy sh-t, this is what I always dreamed of doing - what the f--k are you even thinking?’

So I auditioned and won the audition and it was the beginning of the rest of my life. The first record, I’d only been in the band for five weeks and I didn’t understand where John was coming from. There was a lot of tension between us - he was not in a good mood, just getting divorced and he didn’t want to make a record, but he had to make a record and they wanted to get it done fast and he was looking for ideas from me and my ideas were coming from a different world, fusion and that kind of thing.

Did you have a good idea of what he was looking for?

He was looking for me to answer...when he writes a song, when I was in the band, it would go from him to me. He’d play the song and I’d have to come up with a drum beat and parts based on what he was doing and he would say yes or no. It was a lot of pressure on me. Those beats, like ‘Jack & Diane’ and even ‘Hurts So Good,’ he played the song on guitar and said ‘c’mon, Kenny, what have you got?’ A lot of pressure on me. At the beginning, I didn’t understand the singer/songwriter thing. So the first record, I didn’t play drums on, but I stayed in the studio and watched everything that was going on.

I took notes and that was the beginning of a slow 45 degree angle upward and I vowed I would make the next record, no matter what happened, I was going to make the f--king next record and that’s the one that was ‘American Fool,’ that was a Grammy winner and that’s the f--king thing that launched me. ‘Jack and Diane,’ that whole drum solo and groove, I had to come up with that in the studio and on the spot with fear that I was going to lose my job, because I’d seen two people fired already in the band.

You're on the spot, to put it lightly...

Dude, I was fighting for my life. I came up with that solo, bit by bit, on the spot, right there. I’ll never forget it. Total fear. What am I going to do, what am I going to do? First of all, nobody knew how to make a big drum sound. We spent a whole day trying to mic the drums and blend mics. You can get a drum sound like that in 20 minutes now, but back then, the drums were moved out of the vocal booth into the big room, that was a whole new thing.

Nobody knew how to blend mics, nobody knew how to blend the close mics with the overheads, how high do you put ‘em, how low? How do you do this sh-t? And then, to come with that solo, there was one moment I was walking from the control room back to this drum set going ‘you got 25 feet to save your f--king career.’ 20...15...10...what are you going to do Kenny? They don’t like what you’ve done, you’ve got to come up with something.

I turned around and I won’t bore you with the details, but I came up with a solution as I spun around. The first thing on my entrance is boom-blam and I stopped and John loved it. But what came after that is what they weren’t happy with. What I did end up with on the record was when I turned around, that was what I came up with.

Boom-blam [demonstrates the rest of the famous drum breakdown], that is what I came up with. I had played it, the exact same thing starting on the beat and they didn’t like it. I played the exact same thing, starting one eighth note later and it was just displaced and awkward enough and yet it was, the electronic drum that I had programmed, just moved over an eighth note and they thought it was awesome and I was home free, baby!

And it’s still played on the radio now! And that was the beginning of like ‘who is Kenny Aronoff?’ And then every record was....oh my God, it was one of the greatest, you look back on it, you’re right, you nailed it, there was a time in music that making records was the most exciting moment. It was kind of almost like the ‘60s, but just a new version.

It was like the ‘60s, nobody knew what the music business was, so there was just all this creative sh-t. Every month it was like a new band...it was like what? Queen? The Who? Led Zeppelin? Are you kidding me? They’re all different! And then now in the ‘80s, there was a music business, so people were going after radio, fans and was still raw and creative, but it was getting perfected. It was an exciting time and man, I am so grateful I grew up in that time.

Pat Benatar had an album called ‘Seven The Hard Way’ that related to the fact that she had made seven albums in seven years. Mellencamp kept a very similar pacing on the road and in the studio during the ‘80s and you just don’t see that anymore.

Dude, you are so on top of it. You’re absolutely right. It was eight years non-stop, two years for every record. [You would] rehearse for a record, organize it, record it, promote it and go on tour. Two years. It would take about that long. And then take a break for one month and you’d start again. It was non-stop for eight years.

The problem is now....then, the labels were into investing in a guy like John Mellencamp. They saw that he was a star, but they knew that his songwriting wasn’t phenomenal. But they had the money to invest in this guy. ‘John Cougar’ was the fourth album, ‘Nothin’ Matters and What If It Did’ was the fifth and then ‘American Fool’ was the sixth. It took him six records, but the record labels had money to invest, they believed in it and guess what, they were right, it paid off. He was a star. We ruled.

Nowadays, of course they can’t do that. There is no money. You have to make your own record. There’s no time to develop it and the world is moving so fast that people don’t even think like that. You don’t think in terms of developing my art form and this record is just the beginning, we’re going to work it away. Now, it’s like, we’ve got to have a hit. We’re going to record one song that’s got to be a hit and there’s no money, so we have to do it in some garage band studio and guess what, you don’t have nine months.

But you see, the nine months is what made bands gel and come together. We were salaried just enough so I could save up four quarters to play ‘Space Invaders,’ living in some sh-thole house, but it was enough money, seventeen hundred bucks a month and I could afford to live while my girlfriend was in law school. It was just enough that ‘oh, we can buy a six pack of beer tonight!’

But I was a full blown musician, practicing drums all day long and rehearsing. With Mellencamp, it was a nine hour day, it was like 12-5 and 7-11 and then any other free time, I was practicing the drums. So I was a full blown artist and I didn’t think about anything but that. But nowadays, musicians, in order to be a musician, you have to have a day gig to pay money so you can be a musician and people’s attitudes are not the same.

I was living....you just live in a house and do music, man. You just live it. It’s about being creative and it’s all going to work out and there’s lots of money to make records. Nowadays, there’s none of that.

Well, we should wrap up. Is there anything else on deck that you want people to know about? I feel like we’ve covered things pretty well...

Yeah, I mean, this [Chickenfoot] tour. After this, I’m going to go out with Fogerty and do some stuff. What else do I have going on? [Aronoff pauses to think] There’s always stuff going on with Kenny.....

There’s always stuff, I think we’ve certainly demonstrated that with this conversation. What’s this 2012 entry in your discography for Bob Seger? What’s that about?

[Laughs] You’re good.Okay, yeah. John Fogerty’s doing a duets record, so there I am recording with Bob Seger and John Fogerty in Nashville and it was unbelievable - both of my bosses, so that was incredible. I’ve played with all kinds of cool combinations [for the record].

Very cool!

So, yeah, I'm recording with John and [doing] some touring with John in Europe and the USA and I’ve got my own studio, so people send me files all of the time. That’s a cool thing and that’s an example of what’s going on. I had to build my own studio because that’s the way the world is. People send me tracks from all over the world, I do ‘em at a reasonable price - I record them and send them back to them.

The cool thing is that I’ve played in so many bands that even if people aren’t there, I know how to make it sound like I’m in a band with them. And hey man, I wouldn’t trade anything to have [not] grown up in the time I did. Because it’s like a good bottle of wine, man, sometimes it takes 50 years for it to taste good. Well, I grew up in a time where good grapes run into a good bottle, so I get the benefit of all of that experience.

So that’s why I want to be the Hulk and stay healthy, because I want to see what the f--k I’m like in 30 years!

Kenny Aronoff is currently on the road with Chickenfoot as the band enters the next leg of promoting its 'Chickenfoot III' album. Check out a list of current tour dates here.

More From Ultimate Classic Rock