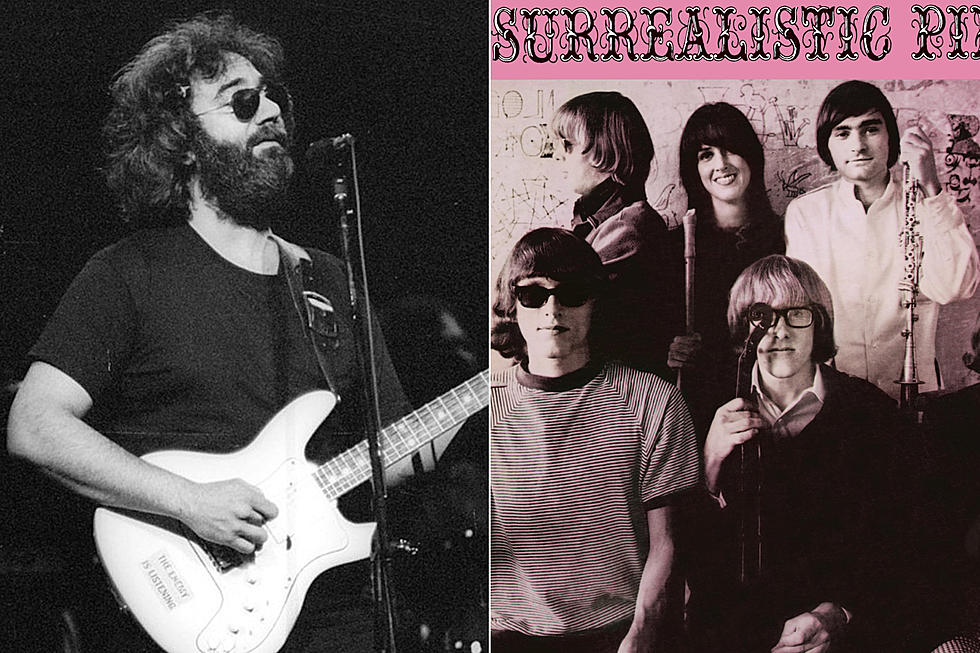

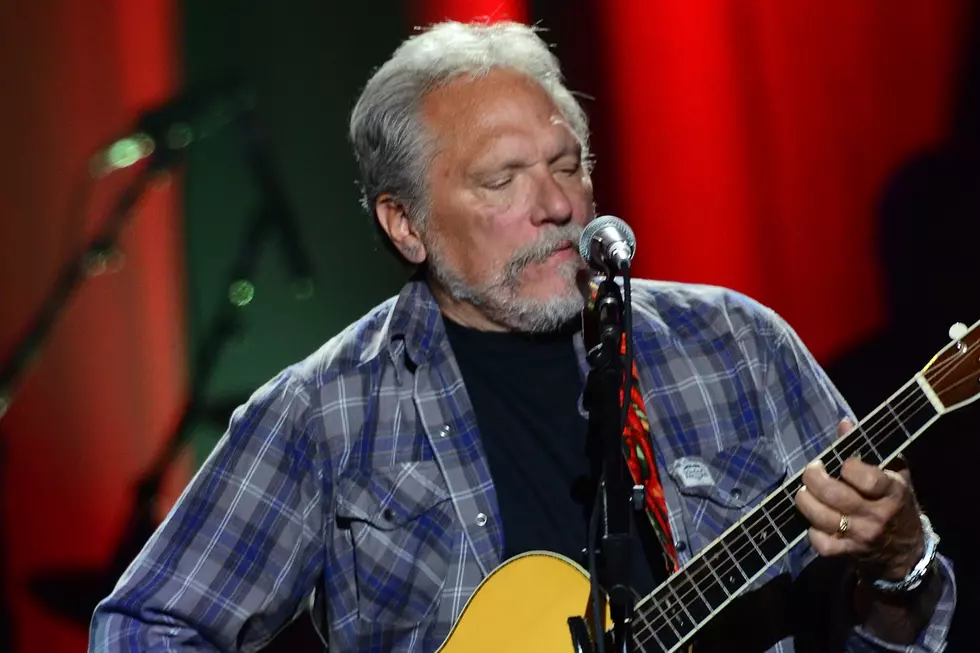

Hot Tuna’s Stop at Woodstock 50 Brings Jorma Kaukonen Full Circle: Exclusive Interview

Jorma Kaukonen will never forget taking the stage with Jefferson Airplane before almost half a million people during the original Woodstock on Aug. 17, 1969, at a dairy farm in Bethel, N.Y.

In Been So Long: My Life & Music, Kaukonen's candid and compulsively readable autobiography from last fall, the guitarist said the experience was like an an excursion into a parallel universe “whose portal opened unbidden and closed just as mysteriously, leaving a vivid memory.”

Billed as “3 Days of Peace and Music,” Woodstock is far from the only highlight in Kaukonen’s career. With Jefferson Airplane, he composed enduring songs like “Embryonic Journey,” his fingerstyle tribute to blues and gospel singer the Rev. Gary Davis. Kaukonen’s arrangement of the folk standard “Good Shepherd” combined acoustic picking, electric shredding and alternative tuning, and has influenced countless guitarists. Later, he formed the offshoot band Hot Tuna with childhood friend and Jefferson Airplane bassist Jack Casady, prefiguring the Americana genre – and they are still touring today.

Among the highlights of Hot Tuna's upcoming dates is a stop at Woodstock 50, to be held in August at Watkins Glen, N.Y. This makes Kaukonen one of a handful of performers at the original Woodstock who will also play during a golden-anniversary celebration of the 1969 festival.

Listen to Jefferson Airplane at Woodstock in 1969

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Woodstock. What’s your insight on the original festival?

There’s a lot of ways to look at Woodstock for someone like me who was there, lo those many years ago. As I’ve said in the book, we drove in, did the show and drove out – though of course we went on 18 hours late. We experienced positive aspects of Woodstock, but we didn’t really experience the whole weekend like some of the other guys and gals did. One of the things that smacks me in the face is how many people were there. We did a lot of festivals back in those days, but that was one of the really big ones. Almost all of the people there didn’t have to show their ticket to get in. That’s not something you see every day.

What is it like returning to the Woodstock 50 to play with Hot Tuna?

This [new festival] is a different ball of wax, but I’m honored that they booked us among these great younger acts. It’s a well-booked show. I hear people complaining, “Well it’s not like the real Woodstock,” but I don’t think they’re trying to recreate that. It’s the 50th anniversary, and they’re putting on a three-day show with a lot of great music. I’m thrilled that they invited us to come along.

In the early '60s, you were still going to school in Santa Clara [Calif., near San Jose]. You were just married and you were teaching guitar and playing in coffee houses. How did you start playing with Janis Joplin?

I met Janis in the fall of 1962. She would come down the peninsula [from San Francisco] to play a gig. Rather than paying somebody from San Francisco to play with her, she’d take the bus and we’d meet up and play. It was such a great time. Janis was so awesome, and getting a chance to play with her is one of the thrills of my life. The Janis that I knew from 1962 to 64 was the folkie/blues Janis. Later on of course, she became rock royalty.

Soon after you graduated, Paul Kantner asked you to join Jefferson Airplane. Why did you say yes?

I didn’t really have any transcendental goals back then. I just graduated from college, so it wasn’t like I had to quit school in order to join Jefferson Airplane. In the beginning, I was still communing to San Jose to teach. I didn’t really risk a lot, and it seemed like the right thing to do. Of course, history has proved that it was the right thing to do.

Listen to Jefferson Airplane Perform 'Good Shepherd'

Jefferson Airplane’s second album Surrealistic Pillow, released in 1967, features your first song, “Embryonic Journey.” What sparked that?

There’s magic involved there. Rick Jarrard, the producer, heard me in the foyer just fooling around, playing that song. He said, “We ought to cut that and put it on the record." I thought that he'd absolutely lost his mind. I didn’t see how a song like that could have a place on a rock 'n' roll record, but he did. There are lots of really great fingerstyle guitar players out there these days, and there may have been back then too, but nobody knew about them. For me to get a fingerstyle guitar piece on a rock 'n' roll album was a big deal.

You followed that up the same year with "The Last Wall in the Castle" on After Bathing at Baxter's.

I started out with a guitar lick and I came up with some words. Then the band encouraged me to put it on the album. That's one of the really great things about everybody in the Airplane. We had so many great songwriters. They could have filled up every album with their songs without giving it a second thought, but they always gave me an opportunity – and I will always be grateful for that.

You're also known as an arranger, and for one arrangement in particular, "Good Shepherd" off of Volunteers in 1969. What was the genesis of that?

I learned "Good Shepherd" in 1952 from this pair of folksingers, Larry Hanks and Roger Perkins. It was the first song I learned with drop D tuning, and [drop D] changed my life in a lot of ways. Fingerstyle guitar players consider it the king of alternative tunings, because it's just such a cool tuning. It was a great song, and it became part of my repertoire. When we were looking for another song to record, I suggested it to Paul, Grace [Slick] and Marty [Balin]. I knew that we'd take it to a dimension beyond the fingerstyle version I played without losing its feeling. In my opinion, we did. That song bears the test of time.

Listen to Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady Perform 'Turnaround'

This year also marks to 50th anniversary of Hot Tuna, the band you started with Airplane bassist Jack Casady. How and why did Hot Tuna start?

When I got in the Airplane, I was an outsider. Paul Kantner was my buddy, but I really didn’t know any of the other people in the band. When we decided to look for another bass player, I’d never heard Jack play the bass, but I knew how he approached music and the guitar, and I knew he would be good. [After Casady joined], we were the two kids from Washington D.C. and we spent a lot of time together. When we were on tour, we would have to double up in hotel rooms, so Jack and I doubled up. I always had my acoustic guitar with me and Jack had built a tiny bass amp. The hotels we stayed in were so cheesy that most of them didn't have TVs, so instead of wasting time watching TV, we played music together. I think Hot Tuna evolved out of that. I remember at the Fillmore East, Paul just said, "Why don't you guys play a couple of songs?" In those days, we didn’t have pickups on acoustic guitars. I just played on the mic and Jack played his bass. We played and the crowd liked it, and I think we just pushed forward with it. The Owsley Foundation just released a CD. [Titled Before We Were Them, it finds Kaukonen and Casady performing a pre-Hot Tuna set on June 28, 1969.] It’s me and Jack and [drummer] Joey [Covington] playing a job up in Santa Rosa. I listened to us playing and I go, "Wow." It’s exciting stuff.

Most people say that Jefferson Airplane were the best band of the psychedelic era. What do you think was the secret of Airplane's success and its seeds of dissolution?

The answer has to do with the disparate bunch of characters that were in the band. We were a talented band and we worked hard, but those two things aren't necessarily good enough. We also had great songwriters, and these great songwriters never forced their ideas on how the songs should sound. They bought them to rehearsal, and Jack, I and the guys just started playing them and things evolved. Nobody ever came in and said, "I want this song to sound like Otis Redding" or whatever. We were always given a lot of freedom. By the early '70s, we no longer had the same kind of committed passion to our vision, like we did in the beginning where we would rehearse seven or 10 hours a day. We were starting to just lay down tracks. Grace would come in and do a part, and then I'd come in and do a part when nobody else was there. It's a way to work, but it's not a magical way to do work. With a band that really works, the whole is so much greater than the sum of the parts. When we were working together, the magic happened. I think when we got into that more cookie-cutter [method], that creative magic began to dissipate. Hot Tuna began to look like more fun.

See Jefferson Airplane Among Rock’s Most Underrated Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock