How Jefferson Airplane Became Jefferson Starship – and Then Just Starship

Between synthesizers, drum machines, and MTV, it'd be hard to pick a single veteran rock act that managed to get through the '80s without being forced to change their sound to some extent.

But where acts like Heart and Chicago may have alienated longtime fans by indulging in extra hairspray and buying a few power ballads from outside writers, Starship paid the highest price of all, trading in the Summer of Love ideals espoused by their original incarnation, Jefferson Airplane, for a handful of Top 40 hits.

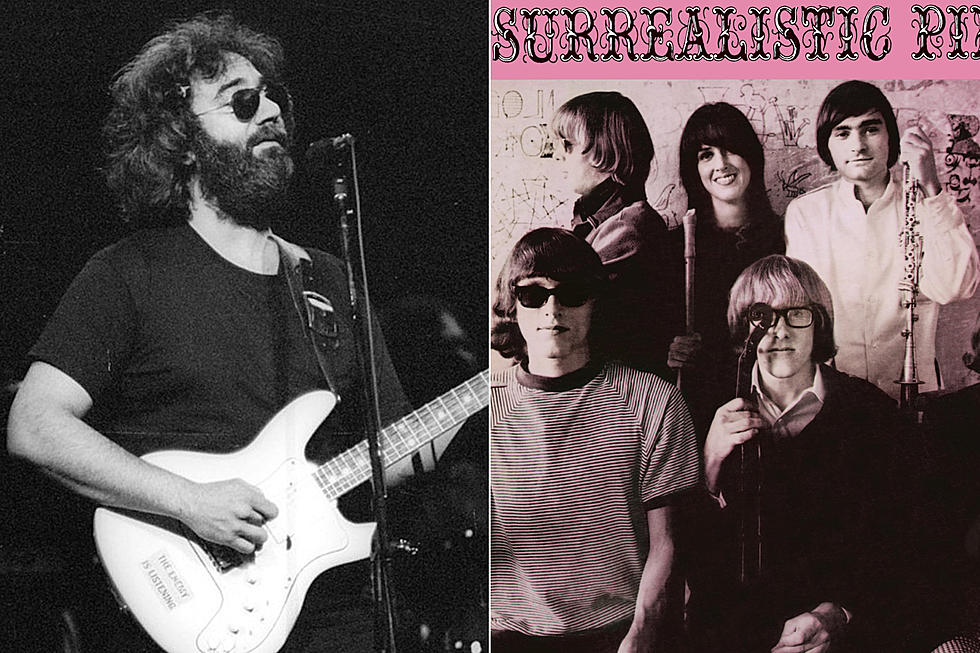

The change didn't happen overnight. Jefferson Airplane actually folded following the release of 1972's 'Long John Silver' album, morphing into Jefferson Starship for 1974's 'Dragon Fly' LP. To say these were transitional years would be an understatement; the Airplane's lineup had frequently been in a state of flux, and so it was with the Starship, with substance abuse, personal conflicts, and disagreements over musical direction frequently polluting the mix.

Singer Grace Slick was forced from the group in 1978 after drunkenly taunting the crowd during a German concert, followed shortly thereafter by guitarist/vocalist Marty Balin, leaving co-founder Paul Kantner to find a new lead singer.

Watch Jefferson Airplane Perform 'Somebody to Love'

That role would be filled by former Elvin Bishop Group singer Mickey Thomas, who'd earlier risen to prominence after being invited to assume lead vocal duties for the eventual hit single 'Fooled Around and Fell in Love.' Jefferson Starship's next release, 1979's 'Freedom at Point Zero,' boasted the Top 20 hit 'Jane,' which pointed the way toward the radio-friendly love songs they'd eventually pursue full-time.

With modern-sounding keys, guitar power chords, and Thomas' elastic voice high in the mix, it fit right in with hits of the day from groups like Toto and Boston.

The fact that this direction was more or less a 180-degree turn from the counter-cultural stance of the Jefferson Airplane's early records wasn't at all lost on the members of the band, but times were changing, and the Airplane's flower-powered political ideals had fallen out of favor about as rapidly as their messily unpredictable (but rarely dull) original sound.

It's hard to argue with hits, however, and for at least a little while, Jefferson Starship managed to find a middle ground that kept the band's old guard happy while still capitulating to FM trends.

Watch Jefferson Starship Perform 'Jane'

In fact, for a brief period of time, it seemed like some members of the famously contentious Jefferson nucleus might actually find something like long-term harmony. Slick returned for some vocal cameos on 1981's 'Modern Times' album, singing a duet with Thomas for 'Stranger' and adding backgrounds to a handful of songs; fittingly, the record included a Top 40 hit ('Find Your Way Back') as well as a 'Stairway to Cleveland,' a profane kiss-off to fans who'd complained about the shift in style.

That balance was too fragile to hold, however. Kantner in particular grew increasingly frustrated with the band's singles-driven focus.

As he told author Jeff Tamarkin for his Jefferson biography 'Got a Revolution!,' "I think we would be terrible failures trying to write pop songs all the time. ... The band became more mundane and not quite as challenging and not quite as much of a thing to be proud of." Things eventually got so bad that, while producer Ron Nevison was prepping 1984's 'Nuclear Furniture' for release, Kantner absconded with the master tapes, holding them hostage in his car for several days until he could get the rest of the band to agree to a different mix.

Shortly after the album was out, so was Kantner – and he took the 'Jefferson' part of their name with him, part of an out-of-court settlement reached after he quit.

Following Kantner's exit, multi-instrumentalist/singer David Freiberg (who'd co-written 'Jane') was also out of the lineup, leaving the five-piece band – with its moniker freshly whittled down to simply Starship – to soldier on with its next LP, 1985's 'Knee Deep in the Hoopla.'

Hired to continue the band's quest for radio relevancy, producer Peter Wolf (not of the J. Geils Band) brought in stacks of material from a roster of outside writers that included Bernie Taupin, Michael Bolton, and Katrina and the Waves singer Kimberley Rew; only one track, 'Private Room,' bore the writing stamp of any Starship members.

It may have been music made to order, but the buying public responded in droves: 'Hoopla' broke the Top 10, spinning off a pair of No. 1 hits ('Sara' and the dreaded 'We Built This City') plus a third Top 40 single ('Tomorrow Doesn't Matter Tonight'). An increasing number of fans who remembered the Jefferson days wondered how their band of rock revolutionaries could settle for mechanized pop songs and corporate-sponsored tours, but as far as Slick was concerned, it was just a gig – albeit one very different from the old days.

"For me, the '80s incarnation of Starship ... felt entirely opposite from the 1969 version of Airplane," Slick explained in her autobiography, 'Someone to Love.' "It was almost like having two different occupations. The two bands had different focuses, purposes, and conduct; one was a circus, the other a musical shopping mall. Starship was a working band: do the albums, do the videos, do the road trips. ... I cut my hair, smiled for the cameras, answered press questions, watched the charts, made the records, and kept my ass out of jail."

Watch Starship Perform 'We Built This City'

Slick had done enough time in the trenches to treat rock 'n' roll like a 9-to-5 occupation if that's what she wanted, but Starship's trajectory continued to cause lineup attrition. Before the band entered the studio for the follow-up to 'Hoopla,' 1987's 'No Protection,' bassist Pete Sears would find his name added to the lengthening list of former members.

"One day, I'm standing onstage, and I'm playing this keyboard around my neck, which I hate," Sears would say, year later. "I'm looking at Mickey, who's lying down on a park bench onstage, with a lamppost as a prop, like Las Vegas or something. I thought, 'What in the hell am I doing here?'"

Sears' absence had little impact on sales for 'No Protection,' which sent the record to No. 12 on the charts in advance of another No. 1 hit (the 'Mannequin' soundtrack anthem 'Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Now') and the Top 10 single 'It's Not Over ('Til It's Over).' But changes were on the horizon yet again: Slick walked away at the end of the 'No Protection' tour, citing Thomas' increasing control of the group, including his decision to cut the vocals to a planned duet (the AC hit 'Set the Night to Music') by himself.

Although Thomas later speculated that Slick may have just wanted him to "look at her more onstage," Slick was fairly unequivocal about her reasons for letting her contract with the band expire, admitting that being in Starship "got "boring after awhile" and saying: "There's no use beating a dead horse. And it was a dead horse as far as I was concerned."

This left Thomas, guitarist Craig Chaquico, and drummer Donny Baldwin as the last men standing for what would prove Starship's final album of new material for many years: 1989's 'Love Among the Cannibals,' released Aug. 15, 1989. Pilloried by resentful Jefferson Airplane fans and criticized by former bandmates, Thomas couldn't resist taking the opportunity to use the name of the new release as a veiled dig at his detractors.

"The love generation was really a bunch of cannibals to me," he shrugged when asked about the title. "That's where I came up with the idea of a bone through the heart for the cover art."

'Love Among the Cannibals' might seem a little snarky in that context, but Thomas was clear-eyed about which side his bread was buttered on – as well as Starship's struggle to maintain momentum.

"Because of the association with Jefferson Airplane and the music of the '60s, any commercial success we achieved in the '80s was viewed by some critics and older fans as a sign of selling out," he later argued. "I'll personally take the hit singles because that, more than anything, has allowed me the opportunity to have a long career.

"Sure, we took a lot of criticism for songs like 'We Built This City' and 'Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now,' but what we created with those songs was a very conscious effort," he pointed out in a separate interview. "We set out to re-invent the band to make it more commercial, and we succeeded in doing exactly what we had set out to do."

Ironically, as the Starship prepared for its next flight, the classic Jefferson Airplane was busy reuniting for its own album, which ended up including a number of pop concessions of its own – including the arguably heavy hand employed by producer Ron Nevison, who later lamented bringing in so many session players to augment the group. "We probably should have just stayed with it, as bad as it was, because technically, the Airplane was never a great band," he pointed out. "I think that if I had paid more attention to it, it could have been better."

Jack Casady concurred, adding: "They had a keyboard player play what he thought was a modern '89 bass part for me. Everybody would go off in their little corner. ..."

In the end, 'Love Among the Cannibals' was nominally the more successful of the two releases, reaching No. 64 on the album charts (behind the No. 12 hit 'It's Not Enough') while 'Jefferson Airplane' stalled out at No. 85. But while the Airplane used the album as fuel for a well-received reunion tour, Starship saw dwindling crowds on the road in '89 – and to make matters worse, their tour ended shortly after it started, when a post-show argument between Thomas and Baldwin following their Sept. 24 gig in Scranton ended in a violent assault that left Thomas so badly beaten he required major facial reconstructive surgery.

"He was one of my best friends in the world until that crazy night," Thomas told the Marin Independent Journal in 2012. "It had to do with being on tour together for so many years in the crazy environment of the road. Being on the road is crazy enough without getting some other factors mixed in there, like resentment and alcohol and drugs. It was a very unfortunate incident that got out of hand. I'm sure each of us would love to go back and retrace our steps that night and make it different, but you can't do that. You change one thing and you may change the whole course of your life."

Watch Starship Perform 'It's Not Enough'

It definitely altered courses for Starship, as the group's promotional campaign for 'Cannibals' tumbled to pieces following Baldwin's firing and Thomas' long period of rehab from his injuries. At a moment when they needed to reassert their relevancy more than ever, the band members were forced to sit idly by while the momentum they'd built up since the mid-'80s vanished.

By 1990, Chaquico was the only remaining band member who'd been part of the original Jefferson Starship, and he could no longer avoid the writing on the wall. "Everyone I had enjoyed playing and writing with over the many years with Starship had left the band, except for Mickey," he recalled. "It became like Mickey Thomas is our star and everything is going to be about him."

Under certain circumstances, having a group's name function as a sales-boosting vehicle for de facto solo records from the last remaining member isn't the worst idea: It's worked well for certain other "bands" in the past. But by the time RCA commissioned a best-of compilation for the spring of 1991, Starship had really ceased to be – not only as a band, but in the minds of record buyers. The fans who'd followed them over from the Jefferson Airplane/Jefferson Starship days were mostly gone, and although their mid-'80s singles had found traction at radio, they were cobbled together from such anonymous-sounding ingredients that they could have been recorded by almost anyone.

Perhaps fittingly, given how many hirings, firings, and lawsuits the group had seen over the years, the end of Starship came down to an executive decision. "I essentially fired the band," longtime manager Bill Thompson later said. "There had been the incident with Mickey's face, plus we weren't selling tickets. I told RCA that we were done."

Of course, band breakups only hold until someone with a claim to the name starts using it to make music again, and by the early '90s, Thomas was back on the road with a new version of the group, which he dubbed Starship featuring Mickey Thomas – not to be confused with Kantner's Jefferson Starship: The Next Generation, which eventually settled back on good old-fashioned Jefferson Starship.

Despite their similar monikers, the bands occupied wildly different ends of the spectrum; Kantner's group harkened back to Jefferson Airplane/Starship's progressive days, while Thomas' crew continued to tour and record in the vein of the band's big '80s hits – something for which Thomas still made no apologies.

"'Love Among The Cannibals' is my personal all-time favorite Starship album. I think it still holds up today," Thomas later reflected. "I think there were a number of factors why the album was a disappointment. It was the first album after the departure of Grace Slick. There was some backlash from the string of hit singles. Also, right after the release of the album we had a serious crisis in the band involving a violent fight that prevented us from touring and promoting the album. It was a huge disappointment, but it's still my favorite."

See Jefferson Airplane Among Rock’s Most Underrated Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock