John Waite on His New Live Album and the Babys Reunion

Everything about the way in which John Waite's new live album came together feels right, starting with how he recorded it. The quest to capture his live band in action began with two shows in Philadelphia. In a sense, the venue for the gigs suits the imagery that Waite has brought to his music over three-plus decades.

“We did two shows in Philly in an old church, bought three kegs of beer per night, threw the doors open, announced it on the radio and 400 people showed up every night," he explains. "It was like playing the Cavern Club. We went out of tune after about the third song because it was so hot! But it was really rock 'n' roll.”

The technical problems would force Waite to record a few more shows and, as he explains during our conversation, it all came together rather organically. He assembled the best material from the recordings, mixed them and released them on iTunes a short time later. Spontaneity is the name of the game these days for the veteran British singer. ‘Live All Access’ is a snapshot of where Waite is right now. But as far as where he might be creatively tomorrow, that’s anybody’s guess; he likes not knowing what the future holds.

During our chat, we dipped into a number of topics, including the reunited Babys -- a recently announced return for the ‘70s rockers that he's surprisingly not part of.

What was your process narrowing the stuff down that ended up on this record? I know your set list can tend to be a bit fluid. I’m sure there were a lot of songs to choose from.

Yeah, there was. But the best songs made it. You know, the European record labels always say, “We want 12 songs and then we want bonus songs,” and you’re going, “What for? Why?” That’s not a record. A record is about 10 songs to play it the right way -- they’re just trying to get something for nothing! I picked the songs that the band played the s--t out of and that I sang the best. It wasn’t like, “This is a hit, so it’s going on the record.” ‘Change’ is on there and ‘Head First,’ but the rest of it is just songs that I love. It’s the first record that I’ve put out where I haven’t gone through a record company. I usually license my stuff to a label. Make the album, license it to a big label and get it back after four years. I bought back ‘Rough and Tumble,’ my last record, after about 10 months. They’d done all they could do with it and I think I got it back for 10 grand. They eventually come back to you, I mean, most of my solo stuff. This is the first time I’ve put an album out where, if you want to buy a hard copy, you have to send [payment] off to the website, JohnWaiteTheSinger.com, and you’ll get a signed copy in the return mail, or you can come to the shows and buy it. But it’s not in the stores. If you’re going to buy it, you have to download it.

The other day I got out of bed and I turned on the computer, and I saw Rolling Stones, ‘Live in Hyde Park’ and I thought, "I’ll have that." I bought it and 10 minutes later I’m brushing my teeth to ‘Midnight Rambler.’ I don’t know really, apart from Barnes & Noble, where you buy CDs anymore. So part of it is me having fun and part of it is me being very proud of what I’ve done and the other part is just kind of seeing if it works to put it out on iTunes. But I don’t have to answer to anybody and I never have -- I’ve always done what I’ve wanted to do and as I’ve said in many an interview, When you’re working with a record company, you’re working with an A&R guy. Some comedian somewhere once said that A&R stands for “always wrong.” It’s very Spinal Tap, but it’s kind of true. ‘Missing You’ almost didn’t get on the ‘No Brakes’ album, because the record company said, "The album’s finished. We don’t need any more songs." I said, “Listen, I’ve written this song called ‘Missing You’ and if you don’t put it on the f--king record, I’m walking.” They gave me five grand and took me very seriously. I went back in the studio and I cut ‘Missing You’ and bing bang boom -- everything changed. But at what point do you not trust your own instincts? I love what I do and I’m good at what I do, and I’m authentic and all of my influences come from country and blues. I don’t really have to ask somebody’s opinion about whether it is right or wrong, I can just tell when it’s right and when it’s sincere. I think if music is sincere, that’s the job, if you want to call it a job. It’s certainly not work, but it has to be the truth and it has to come from your heart. When you have to make decisions by committee, you’re just shooting yourself in the foot.

I’m somewhat surprised you didn’t take the reins back sooner. It seems like you’ve run into what you’re talking about, with label difficulties and stuff like that, with a lot of the albums that you’ve put out over the years.

Yeah, it’s been weird. It’s been really weird. I probably have the weirdest career of anybody that’s still around making music. At some point, this new live record is a knee-jerk reaction against the corporate-rock thing. ‘Rough and Tumble,’ my last album, was really something I was proud of. It was the most unorthodox record I’ve ever made, the way I went about making it.

How so?

I spent about a month or five weeks working with Kyle Cook of Matchbox Twenty and David Thoener in Nashville, recording half of the record and I was going to put out an EP. I went to England to visit my mom and came back, and the management said, “This is so good, we need more.” It’s just typical. I avoided it as long as I could and I couldn’t think of anything to do, because I’d made it to be an EP. It was complete. I wrote down ‘Sweet Rhode Island Red’ on a piece of paper, which is an Ike and Tina Turner song that I’ve always adored, and I thought, “If you’re ever going to do it, now would be a good time to sing it while you’re still young enough to sing it. And then I wrote ‘Hanging Tree,’ which is a song I wrote with Shane Fontayne about a cowboy being lynched and coming back into a new life. It’s about reincarnation. Then I’m looking at these two titles and the phone rings -- this is how weird life is -- and it’s this guy called Jamie Houston that I had written a song called ‘Skyward’ with about four years ago. He said they wanted to do it on 'American Idol' -- “Are you OK with that?” I said, “I kind of recall the title,” because it used to be called ‘Skyway.’ Because it was about a girl that had a drug problem: “There’s a skyway in your eyes where somebody used to be.” It was a really beautiful sad song and we’d made it a happier song calling it “Skyward,” just about walking down Columbus Avenue in New York City in the spring. And I thought, “Well, God bless me, what a coincidence!”

So he sent me the MP3 to the song and I wrote ‘Skyward’ underneath that, so I had three [new] songs. Allison [Krauss] sent me ‘Further the Sky’ and she said, “You’d sing this really well” and me and the guitar player [Luis Maldonado] wrote ‘Rough & Tumble’ the night before I went in the studio. We cut seven songs in three days. I got like three hours of sleep in three days --- gave myself pneumonia, but finished the record, cutting seven songs in three days and it was five days in the studio. I put tambourine on, on the fifth day and on the fourth day, the files weren’t put away correctly so we couldn’t work. So it really was like three days and about an hour playing tambourine. That’s how unorthodox that record was. One half of it was made with precision and the other half was made like you were going to go to jail in the morning and have to finish your work. It was one of those wild things.

Knowing now that you started with that as an EP, how much wrangling did you have to do artistically to get that sequenced to where you were happy with it as an album?

It was the same way that I made the live album. We wrote ‘Rough & Tumble,’ me and the guitar player, with one day’s rehearsal. We flew the drummer in from Alabama and I could only really afford to do one afternoon’s rehearsal, so we played these songs and I said, “Look, don’t worry -- just go in and give it the best that you’ve got.” The guitar player’s tuning up and he played a series of chords and I said, “What’s that?” and he said, “Oh, I’m just warming up” and I said, “No, you’re not,” and I started singing a blues thing against it and I didn’t have the title -- that came to me on day two, but the first thing we cut was [that song] ‘Rough & Tumble.’ You know, if you follow your instincts, you’re not going to regret it if you f--k up, and if you compromise and you put something out that you don’t think is right, it’s the worst feeling in the world. I’m confident enough these days -- although I’ve always been very confident with my decisions. It’s like Keith Richards said about kids and music: “They cannot tell you what they need -- you just look at it and it sort of explains itself to you -- it needs this.” It was made on instinct, the whole thing.

When considering all of the label difficulties and otherwise that you’ve run up against, it’s kind of inspiring that you continue to create. Because I think you probably know that there’s been some of your peers who hit the same level of adversity and they just decide to play the “greatest hits shows” and avoid the drama of making albums. But you’ve stuck to it. Do you still enjoy the process?

I enjoy the process of playing live. Making the live album was really a delight, because I didn’t know what I was looking for, really. I did -- I was looking for Keri and Keri was kind of looking for me. The rhythm section were looking at each other -- we were trying to get used to playing to each other, because it was really working. You should hear it now -- we did a gig about four weeks ago, and Jesus Christ almighty, it was probably the best gig I’ve ever played, and Keri is starting to really, really find his feet. I’m hoping to do another live album in about six months, just because I can and put it back up on iTunes. But the process is with you all of the time -- you walk around thinking about things. You see a kid in the street or you see some old lady or you see a young beautiful girl or you see something going wrong for somebody and your mind sort of edits it. You think of it in terms of lyrics and words and sounds. It’s the artistic process. Without becoming intellectual on you, it’s just something that never stops. I’m falling asleep at night and I’m thinking about it. I wake up and it’s the first thing I think about.

There’s a good amount of material from the latest album that’s on the live album, and you can certainly hear how those songs have developed and grown. For some songwriters, they either like that part of the process or they’re frustrated, wishing that they could go out and play this stuff live and then record it.

Yeah, what are you going to do? As long as it’s dangerous -- it’s got importance. If it can fall apart on you at any second, it’s worth doing. A lot of bands go out and play to tapes and a lot of bands just play the greatest hits, and when I was a kid, I’d go and see Free play or the Who, and they would play a couple of big hits and then go into a Ray Charles song, just because they felt like it. It would be a one-off and it might be the only time they ever did it, but they were in such a good mood or they’d had too much to drink or just the fact that it was all going right, that they just wanted to share it with you. I know that if I bring myself onstage and get to that mic, I’m going to give it absolutely everything I’ve got, and that’s all I know. I don’t want to sound dumb, but I’m working on instincts all of the time now. Your first decision -- Steve Marriott once said this -- the first idea that you have is the best one. You don’t second guess yourself, you just do it. It’s like when you say “I love you” to somebody. You might rehearse it, but you just say it, you know? I think it takes balls to live like that, but I play with people that think like that and that’s where I’m going to be for the rest of my career.

I spoke with Ricky Phillips last year, and we were talking about your ability to take a lyric and deliver it and really make it something. That’s not something that everybody can do.

Well, I’m fascinated by writing and I read a lot and I always have been. I’ve always admired literature and poetry. I read some Walt Whitman last week -- I just picked it up and I was reading through it, and I realized that there was no difference whatsoever between Walt Whitman and Jimi Hendrix. They were both the same person. They were these people that reach for this thing and the bar is set extremely high. But they’re artists and it’s beyond their control. Walt Whitman couldn’t have stopped himself [from] writing ‘I Sing the Body Electric’ and Jimi Hendrix couldn’t stop himself from playing ‘Voodoo Chile.’ It’s a fascinating thing when you really start to look at what motivates art, but I’m a fan. That’s what Pete Townshend said about the Clash, “I’m a fan.” I’m a fan of everybody -- I look at good work and I think “Wow!” Because you’re always looking for somebody to say it and get it right.

Have you started looking toward a studio record with this band?

Yeah, I have a couple of things written, but who knows? We are starting to play bigger places, and I’d like to do another live album before going into the studio. But it’s a hell of a process. Like, I talked about making ‘Rough & Tumble,’ I avoid it as much as I can. I really do -- it’s so intense that it’s like, “Oh f--k, all right then -- here we go.” It’s very satisfying when you finish it, but I’m basically extremely lazy -- I think that’s what’s wrong. But I hope to get in the studio before the end of the year.

In comparison to some folks that avoid the process, you’ve certainly managed to be very prolific in spite of that.

Yeah, sooner or later you have to get it out or you sort of implode. But I’m enjoying playing with the band live so much and it’s such a huge catalog. Keri has brought so much to it that I’m allowing myself at the moment just to really enjoy singing and being alive. It’s the first time that I really feel that it’s great. It’s something that I enjoy the hell out of and I’ve written so many songs that I’m giving myself a couple of moments here just to enjoy playing live.

Your set lists have always seemed to offer equal respect, whether it’s a song from the latest album or a Babys song or a song from, let’s say, the ‘When You Were Mine’ album. It seems to cover the entire length of your catalog pretty well. Are there songs and periods that you find yourself unable to revisit at this point?

We don’t really do any Bad English. I sing ‘When I See You Smile’ a cappella to the audience at the end of the night and they sing along, and then we come back out and do ‘Whole Lotta Love’ [by Led Zeppelin]. We do unplugged bits too -- the ‘When You Were Mine’ album, that’s a serious record for me -- that was one of my best works, and to cut the show and do ‘Bluebird Cafe,’ you could hear a pin drop. To be playing some real full volume rock and then you stop and you play ‘Bluebird,’ that’s what it’s about. I love that song. I wish Willie Nelson would do it. I keep trying to get to Willie Nelson, because he would sing that song better than I sang it. That’s the only song I ever sang in one take. Everything about that song ... my voice was trashed and the microphone that we’d hired had to go back at like two o’clock and I had to sing it and I had hardly any voice. The engineer was kind of speechless and I was speechless, but all of that vocal is one vocal [take]. I love that song, and I think it’s the best song I ever wrote, actually.

I love that record and I love the ‘Temple Bar’ record as well. I think that was a good period for you.

‘Downtown,’ yeah.

Each one of these Glen Burtnik songs that you’ve thrown out into the world, the stuff you’ve done with Glen -- they’re all winners.

Yeah, I just talked about it yesterday on the radio. We wrote three songs, the trilogy of ‘NYC Girl,’ ‘St. Patrick’s Day’ and ‘Downtown,’ and I actually almost burst into tears. We were playing ‘St. Patrick’s Day’ and we played the last verse, “And her red hair tumbles down as she looks up at the sky / He says Jesus Christ, Mary, your eyes are green.” And then he talks about Bobby Sands, who was in the IRA and died in the hunger strike. But he also mentions Beckett and Yeats. St. Patrick’s Day, man, New York City. Glen’s great. I love Glen.

Are you guys still in touch?

Yeah, we tried to write about six months ago, he came over and we didn’t really have it. Maybe next year, you know? Maybe we’ll hit another cycle. [With ‘St. Patrick’s Day’,] I saw this picture on the front of the New York Times on St. Patrick’s Day and there was this procession of firemen marching underneath a banner, young handsome men. And this beautiful Irish Killeen [woman], she had red hair and white skin, she’d run out of the crowd and threw her arms around one of the firefighters ...

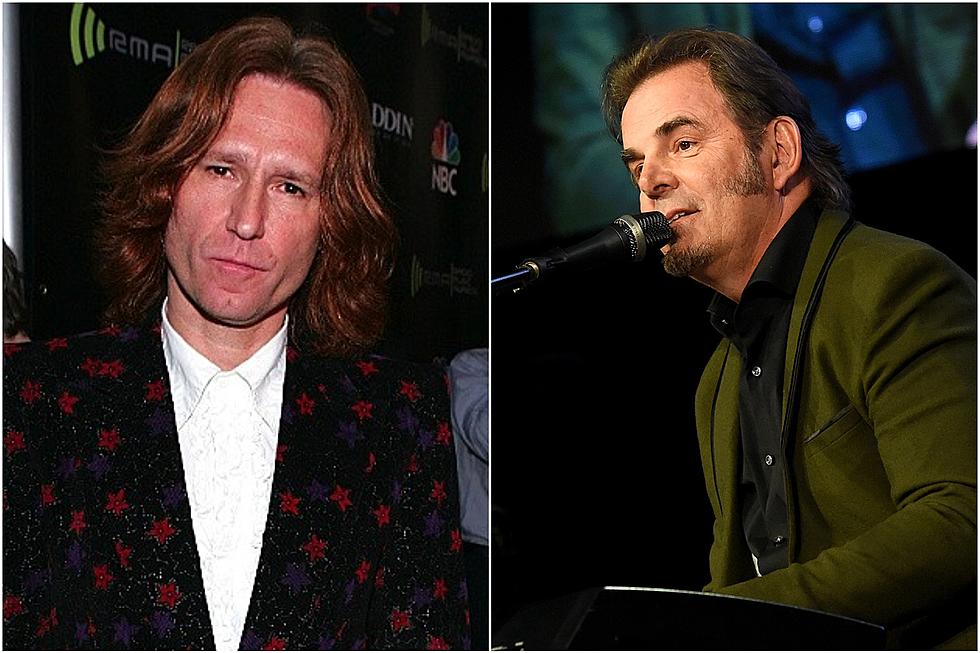

There’s a new version of the Babys going out there without you on the microphone. That has to be a little bit weird for you …

[Laughs] Not really. I feel like all of the pressure’s off me. Honestly, I do. I wish them the best. Nobody’s ever going to say to me now, “When are you putting the Babys back together?” I wouldn’t do it anyway, because I don’t want to go back [to a band], because I like playing solo. But I’m glad that Wally and Tony are playing together again, because they play really well together -- they were meant to play together. If it makes people happy -- and those songs meant a lot to people -- and they can take it to the next step, God bless ‘em, you know?

Do you think that band happened back in the day at the right time? I find myself wondering if there might have been greater success for that band, if that band had come along in the mid-’80s …

Ah, you see. I’m quite contrary. I always try to do things that are quite different, and I always thought that the Babys were five years ahead of everybody else, I really do. They were. We had enormous problems inside the band, in the old version and the new version, it was always trouble. It wasn’t easy at all, but I think we were always ahead of the curve. But the fact that it might have been too early, isn’t that great?

Oh, totally!

That’s the whole point -- we got there before anybody else did and again, we didn’t really know what we were doing. I’m just making up these words and singing these songs and coming in -- I was the only guy that could really write songs. They would play the music super-heavy and make it rock so it wasn’t too poetic. It made a huge difference. Tony and Wally really are [the spirit of the Babys]. They have the soul. I’m surprised they didn’t get back together 15 years ago.

The Babys could fit comfortably in several eras, and I think you could say that about a lot of the other stuff that you’ve done as well.

Yeah, I think the ‘Temple Bar’ album and ‘When You Were Mine,’ that was before country came back and it was [filled with] very vague country undertones and storytelling, especially ‘Bluebird Cafe.’ Things like ‘Suicide Life’ and ‘Downtown,’ that’s about as good as I’ve ever been. Those two records, if I’d have gotten hit by a truck when I walked out of the studio after finishing ‘When You Were Mine,’ that would be my statement and my testimony -- that would have been my life. Everything I’ve done since, I don’t think I’ve ever come close to it, actually. Mike Shipley, who passed away, produced ‘Temple Bar.’ He was the best I’ve ever worked with.

The production on that entire ‘Temple Bar’ album, it’s really strongly mixed.

Yeah, well he’s a classy guy. I was at this tremendous crossroads where I didn’t want to be anywhere near Bad English and I wanted to write about ... you know, ‘Downtown’ was a pretty heavy song to sing and he got it. I wrote ‘Price of My Tears’ on Saturday and we recorded it on Monday. He was just a good guy and I didn’t get to know him as well as I would have liked. He was a little eccentric sometimes, but a very genuine guy. I owe Mike, I do.

More From Ultimate Classic Rock