Isaac Hayes Reissues: Album Review

Had Isaac Hayes done nothing more than co-write "Soul Man," "When Something’s Wrong With My Baby," "I Thank You," and "Hold On, I’m Comin’," we would still speak of him with reverence.

He was a stalwart member of Stax Records' "Big Six" (along with his songwriting partner, David Porter, and the members of house band Booker T. and the MGs), responsible for writing, producing and/or playing on a great number of the label’s classic soul sides in the early and mid-'60s. During that time, however, his job was strictly to feed music to performers with bigger names; his own name was unfamiliar to listeners outside the walls of Stax's studio and offices in Memphis.

That stardom would come only after a tragedy and a business snafu rattled the label. Otis Redding died in a plane crash in 1967, removing Stax's biggest star from its roster and blowing a big hole in the label's collective morale. Then, in 1968, the company's distribution deal with Atlantic Records ended, with all of Stax's master recordings through 1967 reverting to Atlantic. Left without a back catalog, Stax's vice president Al Bell ordered all the label's artists to record new albums, a "Soul Explosion" (as he termed it) that resulted in an astounding 27 LPs and 30 singles released almost at once in mid-1969.

Three classic Hayes albums have been reissued by Craft Records on 180-gram vinyl, with faithful packaging and artwork. Hot Buttered Soul from 1969 had the greatest impact of that brace of releases, and it's easy to hear why. Though the most common forum for expression in R&B at the time was the single, Hayes filled his album with just four extended tracks, filling considerable groove space with long instrumental passages, orchestration and, in the case of the nearly 19-minute take on "By the Time I Get to Phoenix," spoken-word digressions. The album was exquisite, and quite intentionally noncommercial. "I didn’t give a damn it if didn’t sell, I was going for the true, artistic side," he once said. "What I had to say couldn’t be said in two minutes and 30 seconds."

It certainly couldn’t, and if “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” doesn’t convince you of that, Hayes’ 12-minute slow-motion meltdown of Burt Bacharach and Hal David's classic “Walk on By” certainly will. The sprightly three-minute song, which Dionne Warwick turned into a hit a few years earlier, is slowed down and elongated, with gorgeously distorted guitar work by Bar-Kays guitarist Michael Toles, and an enormous wall of brass that makes everything sound bigger. Hayes, though, is in control; the depth in his voice practically gives off its own echo, and he steers the song through the full gamut of responses to heartbreak.

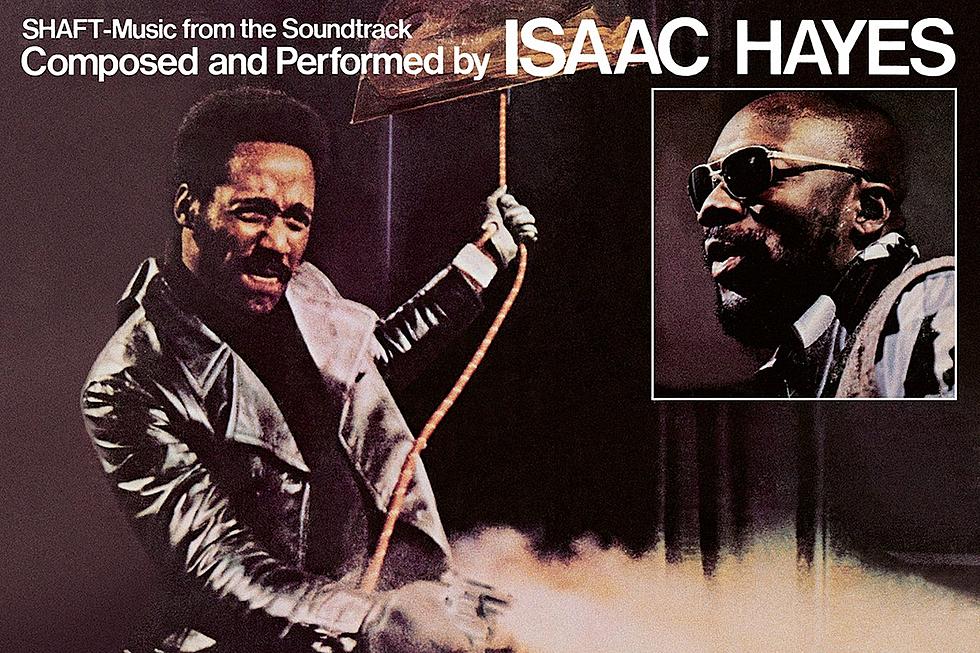

The success of Hot Buttered Soul gave Hayes commercial cache and also helped open other doors for him, particularly in Hollywood, as he began scoring and acting in popular “blaxploitation” films. His first foray into film score was for director Gordon Parks’ 1971 hit Shaft, and the resulting soundtrack album set the standard for other similar film soundtracks in the ‘70s, like Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly and James Brown’s Black Caesar. In the mostly instrumental Shaft soundtrack, Hayes incorporated elements of funk and jazz with his dominant R&B sound, and by doing so produced not just a No. 1 album, but an influential one to boot.

The album kicks off with its most recognizable song, "The Theme From Shaft,” which is simultaneously cracking and smooth, perfectly keying in on the title character, “the black private dick that’s a sex machine to all the chicks.” The 16th note hi-hat rhythm and layers of guitars wah-wahed to within an inch of their lives would eventually become a familiar sound in disco music (along with the horns and keyboards that are layered in), but here they establish the film's cityscape and build tension practically before Hayes even opens his mouth.

A fine counterpoint is the jazz-inflected “Ellie’s Love Theme,” on which vibes and strings carry the melody, while the guitar does some really interesting things behind them, moving from octaves to short bursts of comping to arpeggios, back to comping. “Early Sunday Morning” is languid and sleepy, just like Sunday mornings are for real, while “Be Yourself” echoes old Stax soul sides with the rhythm section providing the engine and the brass section taking the wheel.

“No Name Bar” is another highlight, with slinky bass runs and loud (really loud) brass on the refrains; it’s sexy and heavy at the same time, and features an awesome sax solo. And it wouldn’t be an Isaac Hayes record without a 19-plus-minute track; on Shaft, it’s “Do Your Thing,” an empowerment anthem on which Hayes implores listeners to do the things that make them feel good.

At the height of his popularity, Hayes earned the nickname “Black Moses,” and the 1971 album of the same name was perhaps the apogee of his approach to record-making — a double album full of sophisticated and sensual R&B, packaged in a lavish gate-fold sleeve that opened into a cross-shaped, poster-sized photo of Hayes in full “Black Moses” garb.

Highlights include a languid take on the Jackson 5’s “Never Can Say Goodbye,” in which Hayes’ voice slides around the melody, riding a groove that is pure Quiet Storm (years before the term even existed). He also elongates “(They Long to Be) Close to You” (another Bacharach/David tune, best known in its incarnation as a Carpenters hit) to a tantric nine minutes of orchestral spell weaving and hypnotic phrasing on the verses.

But Black Moses is not always so boudoir-ready. “Going in Circles” features heavy strings that move through the song, rumbling out, then back in, as Hayes gives his falsetto voice a workout. And “Good Love” is just pure, unfettered, testosterone-fueled braggadocio. “It ain’t how good I make it, baby,” Hayes teases, “It’s how I make it good.” "Good" is an understatement for the quality of the music on Hot Buttered Soul, Shaft and Black Moses — they capture Hayes both in his take-off moment and as he achieved cruising altitude.

Top 200 '70s Songs

More From Ultimate Classic Rock