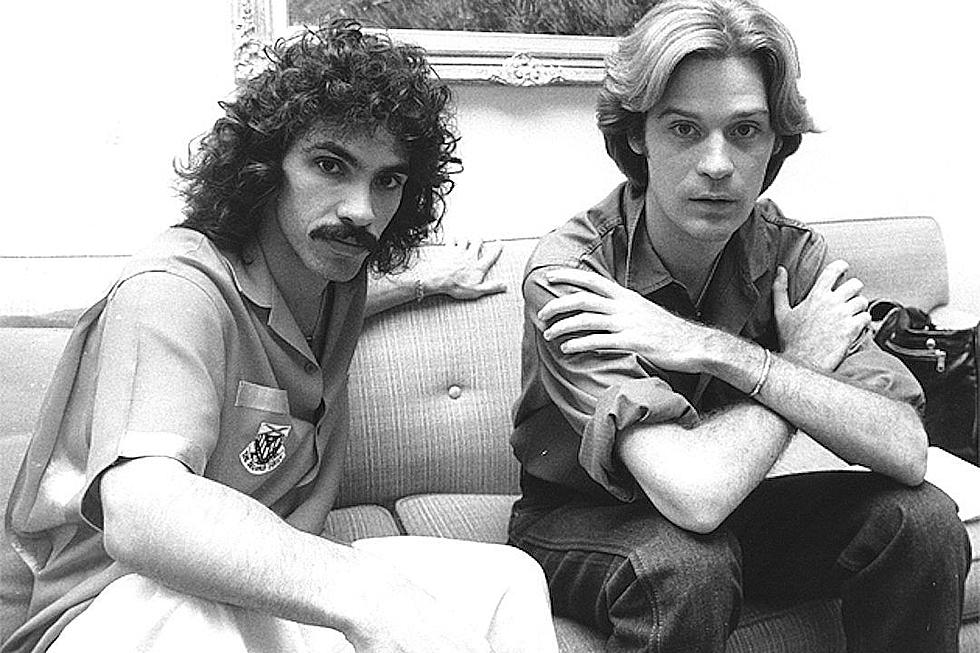

How Hall and Oates Found Themselves on ‘Abandoned Luncheonette’

They're best-known today for the string of enormous hit singles they enjoyed in the '80s, but those days of pop stardom were still a distant point on the horizon when Hall & Oates released their second album on Nov. 3, 1973.

Abandoned Luncheonette found the duo in the studio with legendary producer and Atlantic Records exec Arif Mardin, who surrounded his young proteges with a stable of ace session musicians in an effort to build on the minimal sales suffered by their debut, Whole Oats, the previous year. As John Oates recalled during an exclusive conversation with UCR, it proved a pivotal experience.

"We’d just moved from Philadelphia to New York, and this was the first album we actually made as New Yorkers – experiencing the city, and being exposed to a whole new level of musicianship through the good will and artistic choices of Arif Mardin and Atlantic Records," explained Oates. "We felt like we were where we needed to be. We had high hopes, let’s put it that way."

Remembering the way Whole Oats had failed to make an impact, Oates admitted that he and Hall had "nothing to lose" – and they responded by distilling their influences into a set of songs that unveiled the musical blueprint for every album to follow.

"We look back at Luncheonette as our first record, even though it was technically our second," Oates explained. "It was an album that was made in a concentrated period of time, with a focus and direction, and a group of songs that was very coherent in our eclectic way. The first one was just to get it out of our system – 'We have a record contract, let’s put something out.' With Luncheonette, in that regard, we were really starting out from scratch."

They got to do it in some pretty elite company, too. Not only had Mardin arranged for a coterie of well-known studio vets (including such '70s liner notes mainstays as Hugh McCracken, Bernard Purdie, and Richard Tee), but he'd brought his young charges into Atlantic Studios, where Oates recalls mingling with some of the most famous musicians of the era.

"That space was one of the most amazing, exciting, and inspiring that I’ve ever experienced in my life," he told UCR. "We’d walk out the door and see Bette Midler, Aretha [Franklin], Bob Dylan, Doug Sahm, Led Zeppelin. They’d just walk in – it was crazy. Now I think back on it, and I just wish I’d taken pictures. It was a very exciting time, because we were at the epicenter of what was going on in New York recording at the moment."

That excitement spilled over into the studio, where Hall & Oates were still establishing the parameters of their musical identity, and still had enough freedom to tinker with their formula. Guitarist Chris Bond, who'd end up wearing a number of different hats during the sessions, proved a key component of the expanded blueprint the band laid out for Abandoned Luncheonette, which boasted a far more layered sound than anything they'd attempted for Whole Oats.

Watch Hall and Oates Video for 'She's Gone'

"Chris Bond was a very important part of that, and it would be a disservice to him to not talk about him – as well as Arif Mardin, who was of paramount importance to the way the album sounded," Oates reflected. "Chris wasn’t the producer on the record, but he was an early adopter of the synthesizer technology that was available at the time: He was a bit of a tech-head. We brought an early Moog and an ARP 2600 into the studio, and you’re talking about 1973 here. It didn’t matter to us what we were using, as long as we got what we wanted, and Chris was a really important component of the musicianship on that album."

Unlike later albums, which found Hall moving further into the spotlight, Abandoned Luncheonette contains a relatively even songwriting split, with both partners contributing a handful of their own songs while still making room for a few co-writes. But Oates is quick to point out that just because he might be heard more clearly on this album, that doesn't mean he wasn't a critical component of the Hall & Oates sound later on.

"There’s a little more Oates in an obvious way. Perhaps my songs rose to the top," he conceded. "But what people don’t realize is that I had a hand in a lot of songs, and I made an important contribution to the co-writing of a lot of songs, including many of the big hits. Because Daryl’s voice became the sound of the band, his persona became linked to the focus of the group, and people didn’t realize what I was actually contributing – whereas with Abandoned Luncheonette, there was no focus. We were just trying things, and we were just two songwriters."

Unfortunately, all that freedom failed to translate to major sales – at least initially. In fact, Hall & Oates weren't able to latch onto a national audience until 1975, by which time they'd left Atlantic for RCA, where they scored their first hit with "Sara Smile." Not wanting to let their own portion of the duo's catalog go to waste, Atlantic promptly reissued the Abandoned Luncheonette single "She's Gone," – and this time, it stuck, rising all the way to No. 7 in 1976.

Even though Abandoned Luncheonette wasn't the big break Atlantic may have been looking for, Oates insists it was everything Hall & Oates could have wanted. "We weren’t interested in singles; we were interested in people getting into us in terms of our body of work. No. 1 records are always an amazing door-opener, but that wasn’t where we were coming from: We felt we had made a really great album," he said.

"We became very popular on the college circuit and underground radio embraced the album, and we were totally happy with that. That’s exactly where we wanted to be. So in that regard, we were very successful. We were connecting, getting through," Oates said. "People liked the songs, and they were fun to play, so in that regard, we were on cloud nine.

Listen to Hall and Oates Perform 'Abandoned Luncheonette'

"We got to tour all over the country, and we played lots of places for the first time – everywhere from backwoods towns to big cities, colleges to clubs, auditoriums," Oates added. "We opened for amazing people – Cheech & Chong, David Bowie, Stevie Wonder. So we had all these experiences for the first time behind a record we were really proud of, and people were digging. Everything was all good."

Hall & Oates' albums-first philosophy didn't prevent them from scoring some of the biggest hits of the '80s, and Oates says now that they never varied from that approach – something that's yielded huge dividends in the form of a body of work that's far deeper than radio mainstays like "Private Eyes" or "I Can't Go for That (No Can Do)."

"We treated every album with the same amount of care and production values. It wasn’t like 'Here’s ‘Maneater’ and some other shit,'" Oates explained. "Interestingly enough, it now seems like a new generation is picking up on what I’ll call our deep tracks. I think there’s a lot more musical interest going on outside the ubiquity of those hit singles, and we’re almost prouder of that than we are of the fact that we got lucky and had a few hits."

Going forward, Oates predicts that the lesser-traveled tracks from their songbook will enjoy a bigger place in Hall & Oates' live set list.

"When we put together our box set, everyone asked us if we were going to record together again, and I had this weird quip pop out: 'The future of Hall & Oates is in its past,'" Oates mused. "Because we have such a body of work that’s virtually undiscovered by the average Joe, and I feel that music should be heard. We’re more interested in bringing that aspect back out, and in future tours, that’s kind of where we’re going. It’s more exciting for us."

Ultimately, however many copies it may have sold, Abandoned Luncheonette proved an important turning point for Hall & Oates. It's an album that, as he put it, "pointed the way" toward the records that would make them so ubiquitous in years to come.

"I’ve never been one to make any bets on commercial success. I think Daryl and I have always just tried to make the best record we could in the moment, and if we did that, we were satisfied," Oates concluded. "In the case of Abandoned Luncheonette, we were more than satisfied; we felt we had really found ourselves."

Top 200 '70s Songs

More From Ultimate Classic Rock