50 Years Ago: Badfinger Hit the Big Time With ‘No Dice’

In the late '60s, a band could hardly ask for a better leg up than being anointed by the Beatles — and being given a Paul McCartney original to record — but Badfinger were always about more than their association with the Fab Four, and they proved it decisively with No Dice.

Released in the U.S. on Nov. 9, 1970, No Dice marked the band's second release under their recently adopted moniker, having dropped their previous name, the Iveys, before putting out Magic Christian Music earlier in the year. The first non-Beatles act signed to Apple Records, they'd reaped an immediate windfall courtesy of their new label bosses in the form of "Come and Get It," a Top 10 hit written and produced by McCartney — all of which contributed to a wave of reviews that suggested Badfinger were the Beatles' musical heirs apparent.

Those comparisons would begin to wear on the band over time, but they definitely worked in Badfinger's favor in 1970, when the pain of the Beatles' breakup was still raw and the press was preoccupied with finding acts capable of carrying their mantle (or concocting conspiracy theories about secret reunions). Still, while Badfinger's sound owed an obvious debt to their corporate benefactors, they weren't about to make a habit of relying on outside writers for hits.

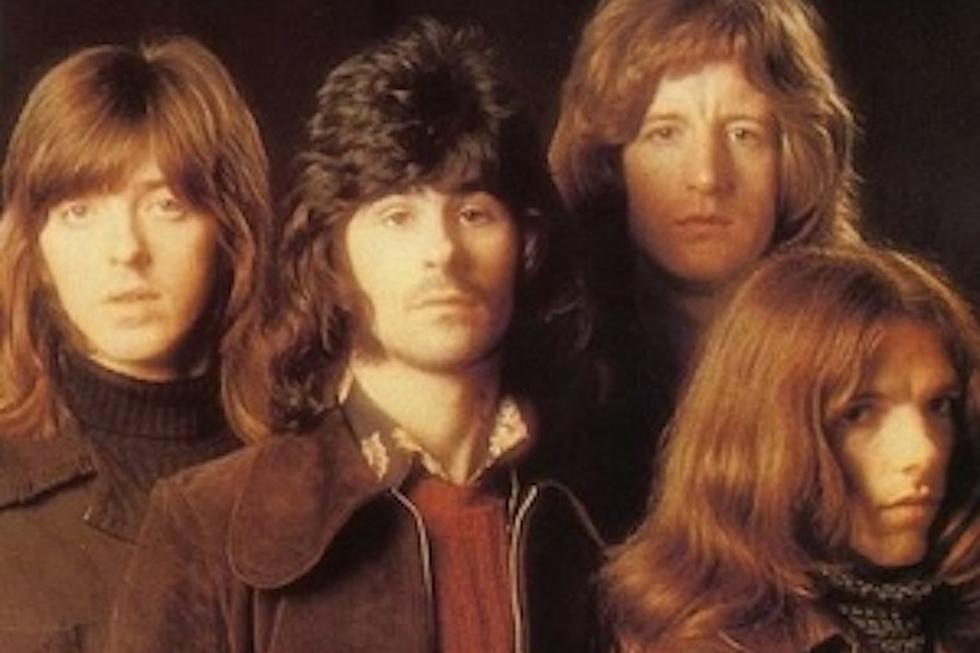

With No Dice, they were aided in this regard by the arrival of rhythm guitarist Joey Molland, who cemented what would become the group's most commercially successful lineup when he stepped in for departed bassist Ron Griffiths. With Molland in the band, guitarist Tom Evans switched to bass, triggering a sonic shift further augmented by the addition of Molland's vocals and songwriting to a creative blend that already included guitarist Pete Ham and drummer Mike Gibbins.

The result was a record that sounded substantially heavier and scruffier than Magic Christian Music — a collection of songs that firmly placed the Iveys' pop sound in the past. "We wanted to be a rock band more than anything else. We didn’t want to be a Disney band. We didn’t want to be the Archies," Molland later explained. "Most of the big hit records in those days were pop songs — you know, 'Yummy Yummy Yummy' was going on then. And the pop fans were very clean cut, and the Iveys took those images."

As they had before Molland's arrival, Badfinger split songwriting duties during the No Dice sessions, with each of the band members landing at least one solo composition on the track listing. That said, Ham exerted arguably the strongest influence on the record, writing or co-writing seven of the 12 songs — including its sole single, the Top 10 proto-power pop hit "No Matter What," as well as the heartrending ballad "Without You," a Ham/Evans co-write whose sweeping grandeur would later make it a massive hit for Harry Nilsson (and, decades later, for Mariah Carey).

Listen to Badfinger Perform 'No Matter What'

The new sound proved an immediate hit with fans, who sent No Dice into the Top 30 while adding "No Matter What" to the band's growing string of hits. A successful American tour followed, suggesting Badfinger were on the verge of becoming the sort of worldwide phenomenon that might have justified the constant Beatles comparisons. Trouble loomed on the horizon, however — and it would not only overshadow the rest of their career, but come to define the story of the band.

During the months leading up to No Dice's release, manager Bill Collins signed the band to a deal with business manager Stan Polley, who overhauled Badfinger's troubled finances by establishing a group corporation and disbursing salaries to the band members — all of which sounded fine on paper, but soon proved less than advantageous to everyone but Polley. In Dan Matovina's biography Without You: The Tragic Story of Badfinger, Polley is shown to have earned more than $75,000 over the year after No Dice came out, while each of the band members made do with salaries and advances of less than $10,000.

More problematic, at least in the short term, was Apple Records' slow slide into chaos following the Beatles' breakup — an issue that would at first manifest itself during the protracted sessions for the band's next album, 1971's Straight Up. After seeing an LP's worth of recordings with producer Geoff Emerick deemed unfit for release, the group hired George Harrison, who spent roughly a month in the studio before letting go of the project in order to focus on his Concert for Bangladesh. Finally, Todd Rundgren was called in for a month of sessions — and though the end result performed well on the charts, producing the hit singles "Day After Day" and "Baby Blue," the band's behind-the-scenes struggles were only beginning.

By 1973, Badfinger were off Apple, and headed straight into a new Polley-negotiated six-album deal with Warner Bros. that called for a new LP every six months. While the band members struggled to fulfill their contractual obligations, money continued to be a severe problem — enough so that after the release of their second effort for the label, 1974's Wish You Were Here, Warners' publishing arm filed a lawsuit, pulling the record from shelves after less than two months of release and cutting off payment for a hastily recorded follow-up effort.

With sales dwindling and money growing ever scarcer, the members of the group started cracking under pressure. Ham briefly quit on the eve of their fall 1974 tour, only to return three weeks later; Molland, meanwhile, left just before the end of the year. Tied up in litigation with little hope of putting out new music anytime soon — or any idea of how to manage financially — Badfinger remained a state of helpless stasis until the morning of April 24, 1975, when Ham hanged himself, effectively ending the band.

Reunions of a sort would continue over the years, with Molland and Evans briefly teaming to record a pair of albums under the Badfinger banner in 1979 and 1981, but poor sales and internal conflicts brought that iteration of the group to a quick halt. After a period in which both Molland and Evans toured with bands under the Badfinger name, Evans hanged himself in late November 1983, casting a further pall over the history of a group whose story began with such bright promise — and whose music still rings with the fresh urgency that made No Dice the first in what should have been a long line of big hits.

The Top 200 '70s Rock Songs

Meet the Members of Rock's Tragic '27 Club'

More From Ultimate Classic Rock