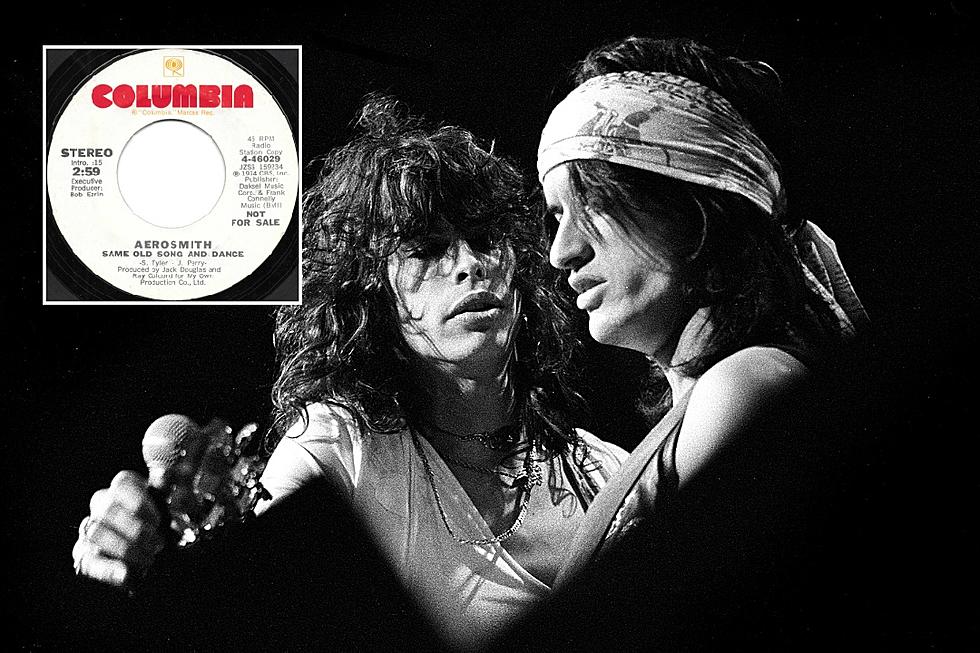

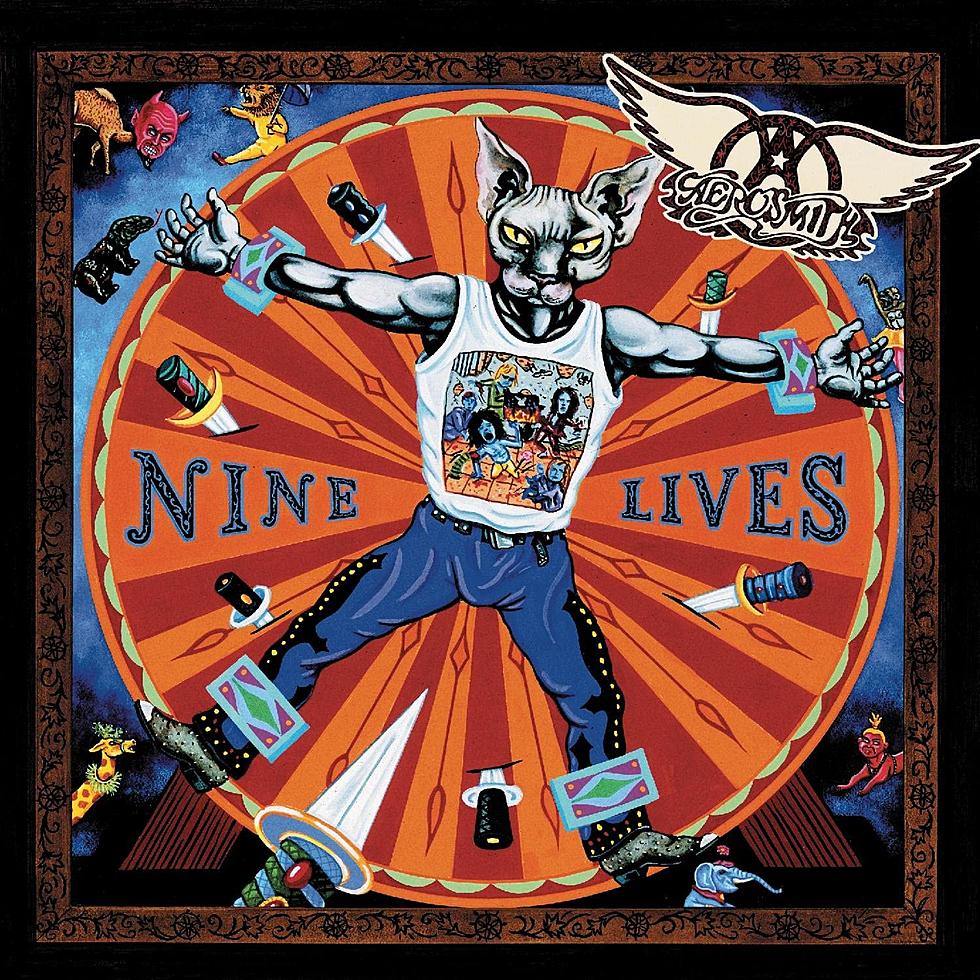

Why Aerosmith Needed Two Tries to Make ‘Nine Lives’

It’s likely that by 1996 no one in Aerosmith expected anything to work out easily. The band’s soaring highs seemed to be almost inevitably followed by swooping lows - less “Will it go wrong?” and more “When will it go wrong?” Their 12th album was titled Nine Lives to acknowledge that state of affairs and its production became part of the group’s continuing cycle of fate.

Work started in the usual manner, with singer Steven Tyler and guitarist Joe Perry engaging several co-writers to work up songs including “Pink,” “Falling in Love (Is Hard on the Knees),” “Taste of India,” “Hole in My Soul” and the title track. Those collaborators included Glen Ballard, who was also signed up to produce the LP. But while Tyler appeared to enjoy the experience, Perry was infuriated by Ballard’s process.

“Joe … eventually threw him out because Glen was working on tracking and vocals and wasn’t paying attention to Joe’s leads or working with him on guitar sounds,” Tyler wrote in his 2011 memoir Does the Noise in My Head Bother You? “So along comes Kevin Shirley, who won Joe’s heart by turning his amp up to 11 and who swore he'd rock the album like it hadn’t been rocked before.”

That wasn’t the first bump. Before that, drummer Joey Kramer was forced to bow out of rehearsals after suffering a mental health incident, fueled by the recent death of his father. As work continued, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers drummer Steve Ferrone was brought in, with the suggestion that should Kramer return, it would be an easy step to replace the drum tracks. But Ballard’s approach to studio work wasn’t as flexible as that. Unlike many rock producers, he worked on the vocals first, intending to add other instruments later. While that meant a great deal of focus landed on Tyler’s voice, it also meant that everyone else was constrained by his virtuosity.

The band moved production from Miami to New York City to begin work with Shirley, and that’s when it became clear that the recordings would have to be trashed to accommodate a more rock ’n’ roll approach. While Tyler admitted Shirley’s reputation as a no-nonsense producer (his nickname was Caveman) was “just what Aerosmith needed,” the singer found himself struggling. “I had to scrap all the vocals and start over, which didn’t come easy for me,” he said. “All the songs on [Ballard’s] Nine Lives would have been great. … Glen had a reason to his rhyme … [but] the last thing Joe wanted was to be told what to do. Another reason why he had him ousted. The funny thing is, Jack Douglas had been adjusting Joe’s guitar timing all the way back to the ‘70s. It's what producers did and still do.”

Watch Aerosmith's 'Pink' Video

Perry recalled attempting to manage Tyler’s “unhinged” moods during the early days of work in New York. “He kept harping on [about] all the time we had spent on the Glen Ballard version down in Florida,” the guitarist wrote in his 2014 memoir Rocks. “I kept saying, ‘The past is the past. Let’s just move on.’ We both needed to vent, and vent we did. Walking to the studio gave us a chance to plan the day and have a few laughs. Taking different side streets, we soaked up the energy of the city, stopping to talk to shopkeepers and street sweepers, some of whom we got to know on a first-name basis. By the time we reached the studio, Steven had calmed down. Then his arguments with Kevin Shirley began.”

It was almost as if a pendulum had swung: Tyler now felt toward Shirley as Perry had felt toward Ballard. In his bandmate’s defense, Perry said, “In the studio, Steven is meticulous to a fault. He'll obsess over the smallest musical detail. Kevin was the opposite. He was going for a raw sound. I was with Kevin, but mostly I kept quiet and let the two of them work it out.” He emphasized that, underneath it all, “the songs hadn’t changed” although they’d been “stripped of their multiple overdubs and rendered with greater grit.”

The result, he noted, was that it took longer than expected to achieve a simpler sonic effect. "Weeks of walking from the eastside of New York to the west-side studio, me trying to chill out Steven on the way," Perry recalled. "Weeks of running down the songs to where Steven would finally sign off on the final version. Weeks of verbal confrontations between Steven and Shirley to the point where Steven swore he'd never work with Caveman again – which was the same thing he’d said about every producer we'd ever worked with, starting with Jack Douglas."

Watch Aerosmith's 'Falling in Love (Is Hard on the Knees)' Video

Nevertheless, it worked out to everyone’s satisfaction. Released on Mar. 18, 1997, Nine Lives continued Aerosmith’s return-to-form streak, although it didn’t do quite as well as 1989’s Pump and 1993’s Get a Grip.

Alongside the production problems, it was created against the backdrop of band manager Tim Collins’ dismissal after 12 years, because Tyler had started to feel that a divide-and-conquer policy was being used against the members.

Kramer, who missed a lot of the negativity, came to feel that his absence was exactly what he needed. “I came back with a nice perspective on what I bring to the table in Aerosmith,” he told Classic Rock in 2017. “That was healthy for me. We ended up rerecording because people were listening to the tracks and were saying some negative stuff about it, and saying the band didn't sound the same.”

Watch Aerosmith's 'Hole in My Soul' Video

Tyler accepted that he could be difficult to deal with, but only because he was obsessed with making the songs work as well as they could. “I just want to marinate in my own creativity,” he explained, likening his process to a game of baseball. “You need a first verse, next a second verse, then a pre-chorus, which is the titillating foreplay, then the cum shot – the payoff – being your chorus line. Then comes the bridge, which should bring you back to the chorus line, then boo-ya ... Score! It’s outta the park. … No one can catch them. They're on the hood of a car on 49th Street from Yankee Stadium. It went where?”

“The album took off, and so did we,” Perry agreed. “The 1997 Nine Lives tour, like practically every Aerosmith tour before and after, was wildly ambitious. We'd cover the world. We'd conquer the world. We were back together as brothers in arms. Once again, the seemingly indestructible Aerosmith machine hit high gear. … Artistically, I felt more alive than ever.”

Soon they’d score again with their only No. 1 single, "I Don't Want to Miss a Thing," but, being Aerosmith, there were more further lows along with highs as they continued into their fourth, fifth and sixth decades.

Aerosmith Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock