How AC/DC Brought Their Live Show to the Studio for ‘Let There Be Rock’

It seems hard to believe all these years later, but AC/DC were dropped by their U.S. record label prior to the release of their fourth album, Let There Be Rock, in June 1977. Even though they already built a rabid following in their Australian homeland, and were showing every sign of doing so in the U.K., the band faced a true career crisis both at home and abroad prior to the recording of Let There Be Rock. Former bassist Mark Evans told Classic Rock magazine that even though the group left for an eight-month British tour as heroes in Australia, its return at the end of 1976 for a homecoming run was greeted by half-empty venues.

It seems some fans had moved onto other groups, while some resented AC/DC for "abandoning" their homeland. "Our grass-roots guys stayed with us, but we got banned from a lot of gigs too," recalled Evans. More bad news came from the U.S., where Atlantic Records called to say that not only would it not be releasing the group's third album, Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, the company was also dropping the band from its roster.

Luckily, the label's overseas division came to the rescue, pointing out that the band had been selling respectable numbers on an extremely tight recording and promotion budget. Deeds wouldn't be released in the U.S. until after singer Bon Scott's death in 1980, AC/DC were given the green light to head into the studio and knock out another album. And they were encouraged to do so quickly.

They were ready. As Evans later explained, "There was always a siege mentality about that band. But once we all found out that Atlantic had knocked us back, the attitude was 'F--- them! Who the f--- do they think they are?'... They were seriously f----ing pissed off about it. We were going to go in there and make that album and shove it up their arse."

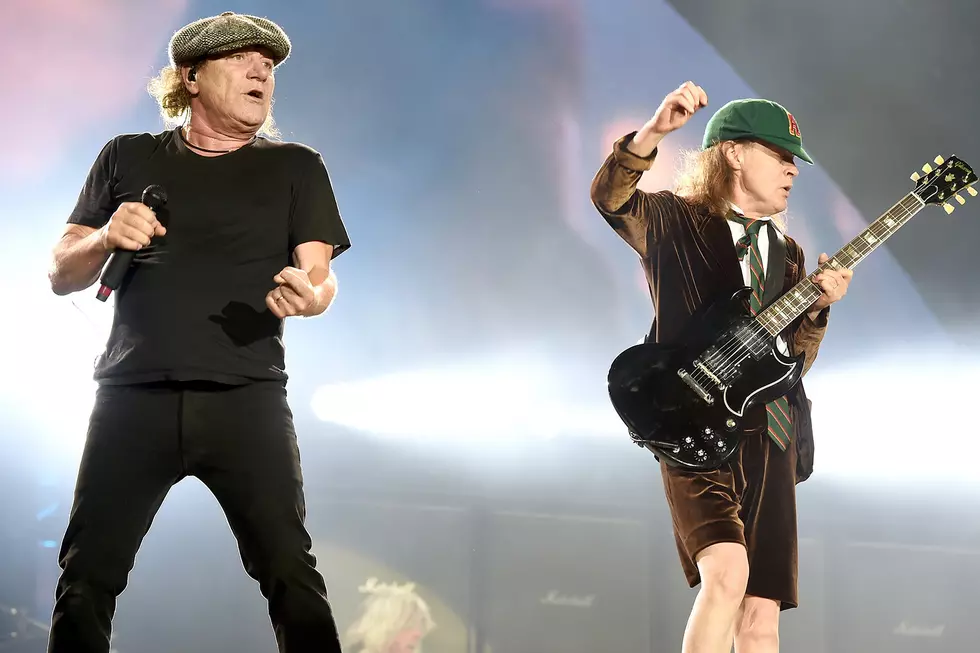

The furious, borderline unhinged results clearly influenced the group. Only the mighty Highway to Hell compares with Let There Be Rock in terms of sheer power, consistency and impact from the Scott era. Three songs -- the strutting "Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be," the charmingly raunchy and fever-pitched "Whole Lotta Rosie" and the title track -- remain concert staples after all these years.

The latter song especially is a highlight: a six-minute epic that seems ready to fall apart in most glorious fashion at about three different moments, only to recover as the band stands behind its singer as he explains exactly how rock 'n' roll was created -- "Let there be light ... sound ... drums ... guitar ... "

Guitarist Angus Young set thetone for the album early in the sessions while recording the song. Even though his amp literally caught fire, he played on, leaving it "a smoldering puddle of wiring and valves" by the end. The track became the group's set-closer for years, and still serves as the vessel to an extended solo showcase onstage.

That same intensity shows up on every one of the album's eight songs. From the salacious and direct opener "Go Down" to the Bo Diddley-influenced "Dog Eat Dog," the slow-burning "Overdose" and the twin trouble-making anthems "Bad Boy Boogie" and "Problem Child," the album rarely lets up.

The LP made only a modest dent on the U.S. chart, but it was clear to anyone listening that AC/DC stared down career failure, reasserted their commitment and served a warning to anybody who even thought about doubting them again.

AC/DC Albums Ranked Worst to Best

You Think You Know AC/DC?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock