A Firm Defense of the Firm’s Underrated LP ‘Mean Business’

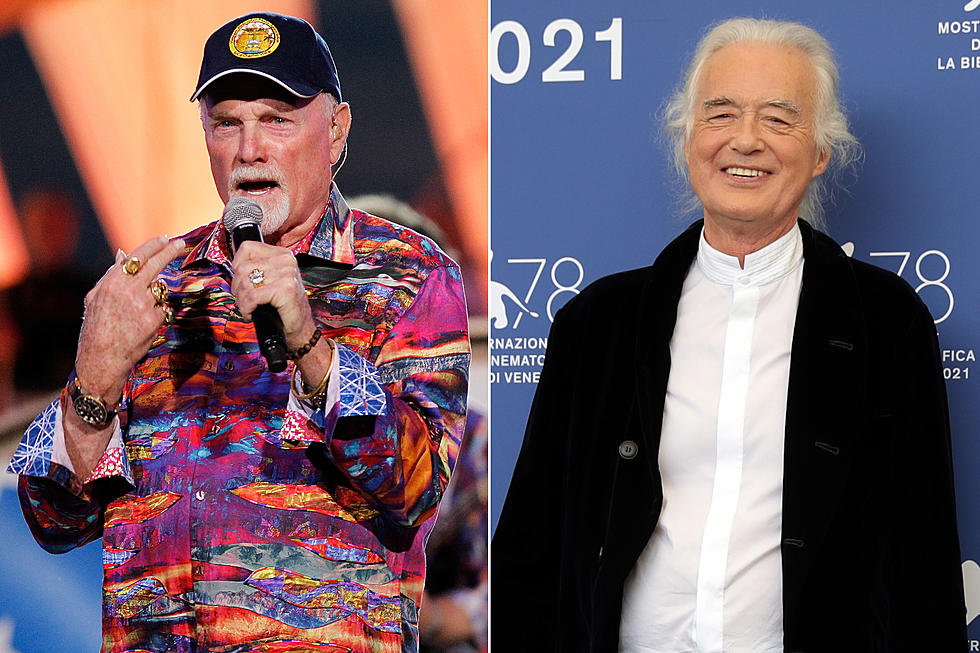

The Firm were not Led Zeppelin, though they had that band’s guitarist. Nor were they Bad Company, though that band's original singer fronted the Firm.

These two facts might have served the band well in 1985, when their self-titled debut made a splash. But after a year of listening and attending shows (in which no Zeppelin or BadCo songs were played), fans might have been looking for more familiar sparks by February 1986, when the group’s second record, Mean Business, was released.

The customers are not always right. Jimmy Page (guitar), Paul Rodgers (vocals), Tony Franklin (fretless bass and keyboards) and Chris Slade (drums) were a supergroup if ever there were one. And while Mean Business was a critical and commercial disappointment, decades later it holds up as a fine ‘80s rock record — one worthy of its creators' pedigree.

One of the criticisms lodged at Mean Business is that a lack of inspiration had settled over Page and Rodgers, resulting in half the album’s first side being pulled from previous projects. But whether Page’s “Fortune Hunter” (exhumed from a short-lived project with Yes’ Alan White and Chris Squire) or Rodgers’ “Live in Peace” (lifted from his 1983 solo album, Cut Loose) were written a week or 10 years before appearing here is really immaterial — it only matters what they did with those songs.

Listen to the Firm's 'Fortune Hunter'

And what they did is pretty awesome. “Fortune Hunter” is a gambler’s tale that takes off immediately, moving at breathtaking pace (not quite “Achilles Last Stand,” but pretty close), with riff, groove and vocal clicking immediately into place. There’s a slight smear of sludge here, too — Rodgers’ vocal is mixed close enough to the instrumentation to make the song sound a little bootleg-y – like you got hold of some secret Led Company rehearsal session or outtake.

The version of “Live in Peace” on Mean Business is clearly superior to the solo Rodgers original. For one, it amps up the song’s inherent drama (and it is a very dramatic song) by removing the insistent drumming from the Cut Loose version, which, particularly in the verses, gives Rodgers ample space to sing alone and ponder the imponderables of life.

Secondly, the presence of Page, Slade and Franklin — virtuosos all — clearly trumps the one-man band approach Rodgers took on Cut Loose by playing all the instruments himself. (Hey, if Steve Winwood could do it, why couldn’t he?)

The results are stagy without straying into bombast — Rodgers standing on the mountaintop, wind and rain in his face, belting out “Why can’t we live in peace?” into the canyon below. OK, maybe there’s a little bombast. But you want that bombast; you need that bombast, just like you need to turn up the volume when you drop the needle on side two’s first track, “Tear Down the Walls.”

And you need to turn up the volume because the song begins with Page being Page, slashing the silence with a riff that practically begs to blow your hair back and nudge the stuff on your coffee table a little closer to the opposite edge.

Listen to the Firm's 'Tear Down The Walls'

Yes, the sound is processed to within an inch of its existence (it was 1986, after all), but with volume, it doesn’t matter: It introduces what could be Mean Business' best song with authority, inviting Franklin’s long bass notes and Slade’s triphammer drum smacking to support it. It also boosts Rodgers’ mightiest proclamations, particularly in the chorus: “I want to tear down the walls!” he shouts at his fair maiden, blowing her hair back. “See them crumble and fall!”

Rodgers need not succumb to grandiosity or epic declarations to get his point across. “Dreaming” is a fine example — the verses are mostly gibberish, and the chorus is mostly pleading: "Don't stop me / I am only dreaming out you baby / A perfect love in a careless land / You're living cold, cold world / You drive me crazy, but you drive me oh ..."

Meanwhile, at least a trio of Jimmy Pages play behind him — one strumming, one picking, one soloing — each one filtered through enough electronic sieves and effects pedals to take up all the frequency space not occupied by Rodgers’ vocal. The sound is less dramatic than elsewhere on the record, but it provides a nice contrast to those other songs, and Page's tumbling solo is a marvel of feel over technique.

In addition to the filters through which Page sends his guitar signal, he also incorporates an odd bit of tech throughout Mean Business. A contraption called a B-Bender, built into his Fender Telecaster, gave Page the ability to bend his B string (the second-highest string on the guitar) up a whole note, providing a more fluid sound in his soloing. Originally used by country and country rock artists like the Byrds’ Clarence White and the Eagles’ Bernie Leadon to mimic the sound of a pedal steel, Page uses it more subtly in the solos to “Live in Peace,” “Tear Down the Walls” and “Dreaming.”

Listen to the Firm's 'All the King's Horses'

He doesn’t use it in his solo on first single “All the King’s Horses” because there is no guitar solo at all — which one might consider odd, were one to forget that the first solo on the Firm’s self-titled debut was by a saxophone player (on "Closer"). No matter. Even with its synths and Humpty Dumpty allusions, this is a heavy piece of work, complete with fairy tales, castles and stormed towers. There's no solo, but Page still raises the level of suspense in the space before each chorus, where his four-note arpeggios form a bridge, enabling Rodgers to bear down and testify to the strength of the illicit love he shares with his fair maiden.

Other songs on the record are equally worth revisiting. “Cadillac” is built atop Franklin’s slippery bass work, giving the Firm member with the strangest hair (electric shock on the top and in the front, braid weaves in the back) an opportunity to shine. “Free to Live” has a Zeppelin-like intro and choruses, with acoustic verses that sound lifted from Bad Company’s Straight Shooter. And “Spirit of Love” closes the album with a bit of hippie-ish philosophizing, broken up only by a cracking Page guitar solo in the middle and at the end.

The Firm found themselves broken up by the end of ‘86. Both Rodgers and Page made statements about how the band was only intended to last two records, but lukewarm sales of Mean Business and its supporting tour likely nudged the two apart once those dates were done.

It’s unfortunate that Mean Business didn't fare better commercially — and that it's rarely ranked highly among fans or its creators. It's a solid rock album with many clear strengths, the final recorded work of a team that could and should have done more.

Top 25 Rock Producers

Was Jimmy Page Almost Part of a New Supergroup?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock