Steve Howe Of Yes On His Departure From Asia, Upcoming Guitar Retreat

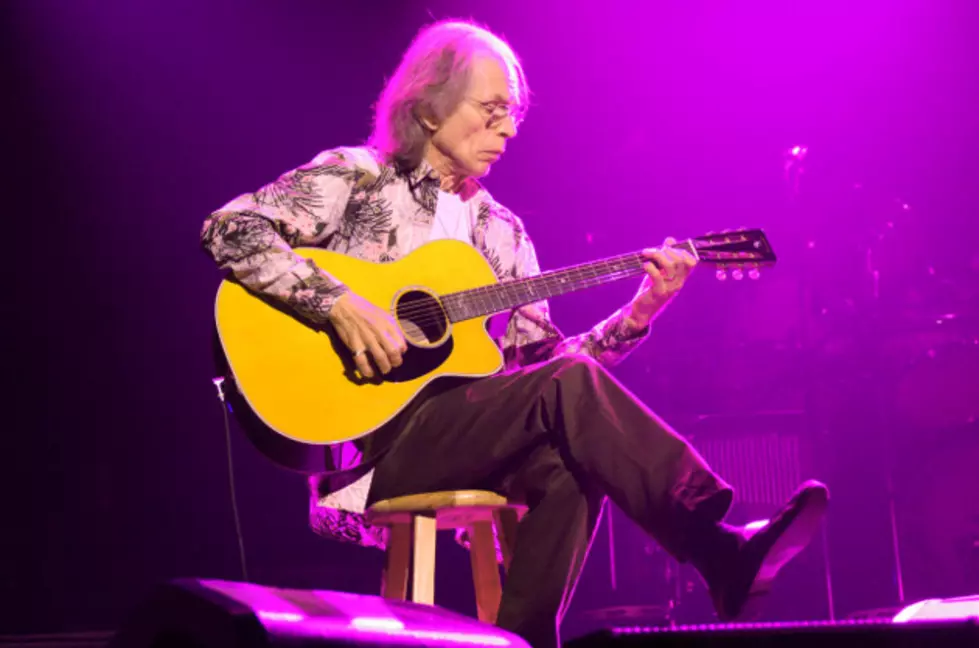

This summer, renowned Yes guitarist Steve Howe will host the first Cross Styles Music Retreat, which is happening at the Full Moon Resort in New York’s Catskill Mountains August 19 through August 23.

The retreat will for sure be a unique experience for both fans and Howe, a respected player both acoustically and electrically. The guitar vet tells Ultimate Classic Rock that he will have a lot to share with those in attendance, drawing from his career of playing music which is now impressively spread across five decades..

We spoke with Howe to find out what to expect and discussed the current Yes tour (which has been extended through the summer), his recent departure from Asia and upcoming plans for new solo work.

You’ve been influential as a player for many other musicians, how do you plan to approach the educational elements of this conference as far as interacting with the attendees and the curriculum part of things?

Well you know, people might was well stay at home if I describe everything I’m going to do. I think it would slightly undermine it. But basically, I come from a different tact from many other people who do these kinds of things. You know, I don’t read music and I don’t talk about 5/4 and 6/8. Basically, I bring my over 50 years of experience of playing the guitar live and [in the] studio.

I think a big part of it [for me also] is about writing music for the guitar and my admiration for Chet Atkins. So there’s a kind of like solo guitar side of this, really, although people obviously want to hear about Yes and presumably Asia and other groups I’ve been in. But the basis for this is much more about the starting point. Because the starting point for my music is actually acoustic guitar. I write on acoustic guitar [and] I arrange on acoustic guitar.

So the central part of this is really the lesser-seen side of myself as well as stylistically, [the] solo guitar playing [which] is central to my work. At various times in my career, it gets a lot of attention, because I need to give it a lot of attention, [because] I love it. So sometimes, the groups make way for events like this. But also, this year, I’m doing a two or three week tour of the UK playing solo guitar.

So this year is the beginning of me revisiting something that’s much closer to my heart than the confusing, conflicting, controversial, annoying, difficult, problematic group life [which I’ve been a part of] for almost 50 years! [Laughs]

I’ve put up with groups over the years, though they are very complicated. It’s a balancing act of other talents and it can almost drive me crazy sometimes, but it is an essential part of my work. But lovingly, solo guitar playing, solo tours and solo projects are like relief from the complexities that go on with groups.

As you mentioned, you are a different kind of player, because you don’t read music. How did you approach that when you began to write your own music and arranging. Not being able to read music, what sort of barriers did that present that you had to work past?

Well, it doesn’t bring on any barriers for me, because I don’t know what it is. I don’t like to look at a piece of paper while I’m playing. I come from a very different perspective and I have no regrets [about that]. Most probably, it’s the opposite, I’m actually pleased that I didn’t learn how to write music, in most aspects.

I’d like to play John Bell and I’d like to play Bach, but the cost of that would have been that possibly, I wouldn’t have improvised. Improvisation is the single most important thing that I do and that’s how I write. I compile ideas and then I start to notice that some of them fit together and then I wedge it together. But then the main thing that compensates for me not writing down what the hell this is, is that I practice those pieces.

‘Mood For The Day,’ the way that was written was that I kept practicing the parts and evolving them together and then when I considered that I was ready to record it, I practiced it sufficiently to be able to play it as well as I did on ‘Fragile.’ So that’s how I compose, through memory.

But obviously, the trade-off of that is that I use a lot of recording techniques to store, compile and reinvent these pieces of music. Otherwise, they’d all disappear down the drain.

So [my process involves] recording ideas on a small handheld digital recorder or putting them as they used to be, on cassettes and things like that and basically just going back to your music and putting things together. That’s a nice problem and it’s not something I have to allow myself time to do. I find that the winter months are the best times to do that.

So I’ve just done that thing a little bit recently. January and February were partly absorbed in looking back at ideas I’ve got and finding out whether or how, which way they fit together. So as I said, there are no regrets about...well, there are no regrets, but the compensation [that is required] for not learning to read music is that I’m a furious improviser. That is a big compensation.

There are a couple of additional players who are going to help out with the instructional elements of the camp. I know you’ve done some work with Ray Matuza in the past, but how do you know these two guys?

Well yeah, Ray, I’ve known much longer. Flavio is a new friend. I was in Venezuela about four or five years ago and a guy just came up to me and gave me a couple of CDs by Flavio Sala and I played one and thought “oh, that’s quite nice -- it’s a bit [of a] crossover” and then I played the next one, which was all Venezuelan music and I was utterly, totally captivated and blown away by what this guy had done. He compiled together beautiful versions of what feels like [something that was already] in my blood, music that I didn’t even know was Venezuelan. So I was impressed not only at his ability to make a repertoire on a CD work so well, but his playing was sound and his technique just blew me away.

So as I do, when this happens, [as] it happened to me when I first heard Steve Morse or Martin Taylor or other people, I personally get off my ass and say “I’ve got to find this guy” and “I’ve got to reach out and say look, this really knocked me out.” So I did that with Flavio and then we met up. We started meeting up and we have recorded a tune together that we’re both sort of holding back to see how we use. So we’ve done a duet together.

But in the meantime, we’ve also talked about the guitar immensely. We’ve spent many hours sharing and trading different things, because I’m fascinated that a young guy of 30 has got the classical guitar repertoire at his fingers.

He plays a beautiful guitar that is made in his hometown and basically, he comes as a all-around package. He’s also broadening his horizon from classical into flamenco which is a logical thing for him to do, I think and [while] I’ve certainly encouraged him to do that, he was doing it anyway. He’s [also] quite new to improvising, which he’s extremely good at. So as I said, he’s an all-around package.

Ray goes back years and years with me. I met him back when there was a magazine called 20th Century Guitar that I was heavily involved with. Scott Chinery was a great supporter of this magazine and [editor] Larry Acunto was the boss. He introduced me to Ray Matuza and Ray was a very enthusiastic and capable, brilliant guitarist of many, many styles. We started kicking around some stuff and he did some support playing with me on some shows that were one-off shows, more or less private shows for the 20th Century Guitar magazine which is now deceased, of course, primarily because of the economics. It was a terrific magazine and it really did concentrate on the great archtop guitars, which are central to my sound.

He’s got a lot of teaching experience and also he’s got a lot of Steve Howe familiarity -- he’s able to talk about my music in the other way that I don’t and I think that’s a great compliment to what I do and the key to this is always personalities. Because no matter how good a player is -- in fact, there were some extremely good players who were extremely difficult to be with -- one does look for in this business, people who have got some people skills at the same time as musical skills. Because without them, you know what? Give me a rest -- get out of my life! [Laughs]

I mean, it’s just not worth it and I guess as you get older, which I confess to being, it’s even more important. You realize that music is about a very special kind of communication that’s pretty unknown. It’s not easy to discuss it but people’s personalities and their honesty, their reliability and the fact that they’re not going to stitch you up and the fact that they’re not on an agenda about some other thing that you don’t know about, all of that stuff is history with me. I can’t work in an environment [like that] and maybe I’m spoiled because in my solo projects, I am in a hundred percent positive environment because there isn’t anything in there that stinks. But there are at times difficulties working with other musicians who don’t have natural people skills.

The solo shows that you’re going to be playing this year, are those going to with your trio or just you? What’s the format going to be?

Well, [I’m playing] one in June [and that one] is just solo guitar and then in September in the UK as well, I’m doing [shows with] the trio. Because similarly, the trio is something close to my heart and also has taken a serious backseat for a couple of years after we released ‘Traveling,’ which followed on from our studio album, ‘The Haunted Melody.’ But basically, that’s a project that yeah, it can stop/start a bit and obviously I love playing with Dylan [Howe] and Ross. Ross Stanley is a tremendous organist and keyboard player.

Obviously, I like working with musicians that I admire and Dylan’s drumming has developed....I think he started when he was about seven and so he’s been playing a phenomenal amount of time and we spent a lot of time playing together. In fact, since 1993, he’s played on all of my solo albums that require drums. You know, they say that blood’s thicker than water. You look at somebody like Dave Brubeck who played with his sons and I was always amazed that he did that. But I started doing it and I realized that it’s a wonderful thing.

The trio is working in April on a new recording and we hope to have that out with the tour in the UK. But I’m kicking off with the solo stuff and I guess that’s because I’m itching. [Laughs] Give me that taste and let me talk a bit about Chet Atkins and Big Bill Broonzy. Let me play that music or draw from that well of musical guitar inspirations that I’ve had.

Seeing Wes Montgomery play when I was 16 is still having an effect on me and I saw Chet play two or three times. So those are the kind of high musicians that I attempt to bring into my life.

Those solo shows, just the activity that you did touring under the Steve Howe name, that was a large part of your musical existence in the early ‘90s and it seems like that would find you developing further as a player in interesting ways as a result of that roadwork perhaps in ways that weren’t happening in the group format.

That’s true, yeah. It’s a challenge to invent a solo repertoire and performance to do that. Now, it’s been at least three or four years since I’ve done it at all and they were quite short legs [at that time]. So yeah, I would like to think I’m going to rethink it and come at it from a slightly different angle. But I’ve got some more tunes to play because since [the album] ‘Motif Volume 1’ [came out], where I did tunes like ‘Cat Napping’ and ‘The Golden Mean,’ I haven’t done those in a solo show. And also ‘Solitaire’ from [the Yes album] ‘Fly From Here,’ so in a way, there’s been a nice accumulation of more tunes that I can interject into my solo work and one of the most difficult things is deciding really what guitars to use.

Because I do have a choice and it’s a fantastic choice from the Theo Scharpach SKD is a terrific solo performing guitar and obviously my relationship with Martin is very central to my solo guitar performances as I use an MC-38 Steve Howe onstage, the cutaway version of a previous guitar that I was using, the MC-28. It’s decisions like that. My Spanish guitar is still working pretty well, so I like to keep simplifying my life but at the same time in some ways, it’s quite hard to do that! Because before I know it, I’m thinking of taking a Spanish....a folk guitar, maybe and maybe a Variax.

It’s still quite central to the colors that you can immediately create from one instrument. I think most of the guitar world has missed out on that guitar, which is good for me, but I don’t see why other people haven’t adopted it almost as much as I have. And then there’s 12 string....and will I do a few songs and do I want to sing? So there’s a lot of fascinating questions to answer, all of which I enjoy and I have to come to my own conclusions.

But with the trio, with our collaboration next month and [also] during May, we’re going to do some work and dabble with some recording. Much like I pushed Asia and Yes to keep reinventing themselves, the trio is going through a bit of that. We may decide to do a completely original record this time without any jazz or blues references. We may not get that far -- we may decide we like something and we want to do it, but we’re certainly going to combine musical styles to come up with another phase of the trio.

Did this push you at all towards your recent change that found you stepping away from Asia? Because it seems like this has finally opened up the time for you to do a project like this or do something like the retreat that might not have been there before.

Well certainly, something had to give. Because I’d just done five years with both bands and then Geoff had joined [Yes] when we did ‘Fly From Here,’ which is maybe a lot shorter, only a quarter of that time for him. He only experienced the tip of the iceberg of being on call for two bands. But there were times in the first three years -- it actually got easier when Geoff joined. It was easier because we were both in the band and we could both wrestle with the schedules -- but before that, at times, Yes or Asia would extend a tour by a day and then Yes or Asia would then expand the start of the tour, so the gap would start to close.

And I would start freaking out saying “yeah, but hang on -- if you add that date here and they’ve just added this date here, I’m now squeezed like a concertina.” So there was going to be a time at some point when this was unworkable and unfortunately it was was the end of last year that made me realize that this being on call was really too much. I couldn’t keep either really happy. I was either making Yes miserable or Asia miserable, because of the other one being in existence.

So I think that Asia had a terrific run and we made three great albums. In fact, ‘XXX,’ I think is a fantastic record. Mike Stone did a brilliant job on it, helping us arrange and record that record in the most efficient and beautiful way. I think the sound on it, some of the guitar sounds, are every bit if not sometimes better than what Yes had done. ‘Fly From Here’ wasn’t so bad, but he really got some beautiful [sounds]. We used the [Gibson ES-] 175 quite a bit -- a variety of guitars as usual. But wow, Mike did a wonderful job.

I have to ask about the current tour. Besides playing the three full albums, what’s been the most interesting part of the shows for you?

I guess songs like ‘Turn Of The Century’ for me are some of the most challenging [songs to play], but also [bring] the most rewarding moments, because it’s the contrast in Yes that makes it so great. And going from the song ‘Going For The One’ straight into ‘Turn Of The Century’ as the record does. I would say first of all that the most enjoyable thing about it is that we don’t play songs, we play albums. And that is really quite different. We haven’t done that since 1973 when we used to go out and play the ‘Close To The Edge’ album and then we played ‘Tales From Topographic Oceans’ and that was a huge set. It was a marvelous experience and we completely dropped that. We never did that again. So the fact that they listened to me for a couple of years that we ought to be doing albums on our tours and finally got on board with it [has been great].

There’s been a few internal ordering issues [with] different people thinking that we should do them in anything but a chronological order. I’m completely chronological in my mind, but unfortunately at the moment, we don’t play them chronologically so I’m not totally happy with that.

Not playing them chronologically makes utterly no sense to me whatsoever. I’m not the only person who thinks that but not everybody thinks that. So there’s an internal combustion going on as usual in Yes where the order of the albums is seen to be something we can change. Which you can’t change the fact that ‘The Yes Album’ came out in 1971 and you can’t change the fact that ‘Close To The Edge’ came out in ‘72 and you can’t change the fact that ‘Going For The One’ came out in ‘77. You can’t change that fact. To me, it tells a beautiful story of our naive, wet behind the ears ‘The Yes Album’ to our expansive ‘Close To The Edge’ development to our almighty reunion sense of openness and beautifulness with ‘Going For The One,’ with songs like ‘Turn Of The Century’ and ‘Awaken.’

They are a long way from ‘Perpetual Change.’ I love them all and they’re all dear to my heart and I helped write many of them, but I would say that to me, it’s blindingly obvious [and] it’s a no-brainer, if you like, that we would chronologically do the albums. But there’s another agenda and it’s a confusing issue. We keep changing it and trying it different ways around. Very rarely, do we actually go back to the logical chronological [sequence] which I think is perfect.

So in essence, it’s things like the big pieces like ‘Awaken,’ that we brought back last year, that are very central to what I think Yes really achieved. Sure, there are other nice songs that we do, the shorter songs, but it’s the big pieces that really helped define what the Yes stamp is on a piece of music. When it’s 20 minutes long, you can definitely say that’s Yes! [Laughs]

That’s what I think is interesting about the albums that were chosen for this tour, is that I do think that each one shows the band at an interesting stage in the period of development. Can you describe the process of working on the ‘Close To The Edge’ album? It seems that with the overall length of the pieces on that record, it would seem that you probably spent quite a bit of time working out those arrangements. And there were probably quite a bit of negotiations to make that happen.

Yeah, I mean, when Jon and I got the overall structure for ‘Close To The Edge,’ we presented it to the band. But everybody was petrified when we went to them with [the plans for] ‘Tales Of Topographic Oceans.’ Chris [Squire] Alan [White] and Rick [Wakeman] were all like “you’re kidding us....I mean, have you guys gone crazy or something?”

They were a little bit like that on ‘Close To The Edge.’ They were a little bit like “wow,” but basically the construction....I say this regularly when talking about any recording that Yes did. When we went in, we’d already rehearsed ‘Close To The Edge,’ the tune [and] ‘And You And I.’ But we always made them about 50 percent better. The refinement of getting together with Eddy [Offord] and getting in the studio and getting the solidness of the sound right, we could then tweak the arrangements, find endings and do things that we hadn’t detailed before. ‘Close To The Edge’ was a perfect example.

I remember [that] like many recordings, we streamlined the band to a three piece to get the backing track down, focusing on the bass and drums and getting me to do a guitar [part] that’s either a keeper or it’s a rhythm guitar or it’s never going to be heard by anybody. It didn’t really matter -- I didn’t need to know that at the time. I had the choice of later saying “I like that” or “I don’t like that” or “it’s of some use in the rhythm context.”

Much like on ‘Close To The Edge,’ there is an electric rhythm guitar that comes in sometimes that obviously was the first thing I played. But certainly the whole introduction was recorded live. The only overdub was the keyboard and the harmony guitar on the first 32 bars of that tune. But basically, Bill [Bruford], Chris and I went in the studio and had an idea which was that riff and we basically jammed on it and came up with those strange stops and all of those things. So that was a new step. Bill often said to me [previously] when I overdubbed a guitar break, “why haven’t you played that before? I would have never have played that [part the way that I did]!” So I liked Bill’s honesty towards that, “oh, that’s a nice solo, but I wish you’d played it when we did it, because then I could have played the right thing!”

So ‘Close To The Edge’ came to fruition in a way because he was there when I was playing that stuff. The construction, we didn’t do it in one day, that’s for sure. The backing track itself probably stretched three days of recording. We’d go in and work as much as we could and get as far as we could and go to the next station and at most, it probably took us at least a day to get to the void and then there was probably day working on voids and church organs and stuff and then “how are we going to finish this song?”

I’m totally inventing this but it might be quite close to what happened -- I don’t remember exactly how long some of that stuff took. But what we did then, what was particularly important about ‘Close To The Edge’ is that it became the model for ‘Relayer’ and it became the central idea of what Yes could do [with an album] like ‘Tales,’ which was an expanded ‘Close To The Edge.’ We went back to ‘Relayer,’ which was really the identical plot for ‘Close To The Edge’ and then ‘Drama’ was a bit like that too, we had a really big piece, so the other pieces on there were just fantastically opportunist, production-wise, particularly ‘And You And I.’ We did that with ‘Your Move’ and some other songs where we basically clicked it and I went out and played guitars to start certain sections going and then the band.

I can’t remember all of the details, but Eddy at the time on those first three albums, he was about as brilliant as anybody could be with helping us cross borders and cross old fashioned methods of recording. It was out the window -- just forget it. We’re going to make our records the way that we want to make them. And fortunately, because we got great results from everything after ‘Fragile,’ Atlantic and Ahmet Ertegun, who I thought was one of the greatest people in the music business ever, he just came around occasionally and said “how’s it going?” He’d always say to me “Steve, tell me how it is.” He seemed to believe that I was going to be totally honest and straightforward with him.

I dearly loved him. He was a great mentor for me and almost introduced me to Gil Evans, to do an album with Gil Evans, but that just didn’t happen in time unfortunately for me and Gil Evans. So there was a label, there was a band and there was even a manager. Yes was a full-tilt group and certainly with ‘Close To The Edge,’ we were trying to make the biggest breakthrough we could and I guess it did achieve that for us.

When you came into the group with ‘The Yes Album,’ did you see that potential already, that perhaps you would end up doing some really epic pieces with the group?

I don’t know if the symphonic scale was in my mind, but certainly the ambition to meet other people who were equally ambitious [was there]. I went to other group auditions, some of which have been charted slightly inaccurately, but I followed up on other group offers, which included Atomic Rooster, Jethro Tull, The Nice and other groups like that. It didn’t seem right. There was something kind of missing. But I think when I walked in that room with Bruford, Kaye, Anderson and Squire, I think there was an ambitious electricity in that room.

Bill was totally unconventional. He said “oh, I’m not going to play 4/4 -- don’t ask me to play 4/4” was one of his classic lines. His best one was that we were just going onstage and we’re just about to walk on and he’d go “guys” and we’d say “yeah?” and he’d say “look, I’m going to change all of my drum fills tonight” and we’d go “oh, Bill, please don’t do that.”

“No, no, I’m going to do it -- I’m just telling you that I’m going to do it.” We’d get onstage and not one drum fill would be recognizable. It really kept you on your toes. If you weren’t sure, you had to count or if you believed in yourself enough, you knew that Bill was going to [change things up]. So there was that kind of ambition. It wasn’t really, it appeared to me, [it was] not about ego or financial return, but actually about making the biggest mark that you could as a musician, which of course we’d seen other people do. I’d seen Frank Zappa do that. We’d obviously seen the Beatles -- we’d seen people make a huge impression and that seemed to be the ambition at that time.

More From Ultimate Classic Rock