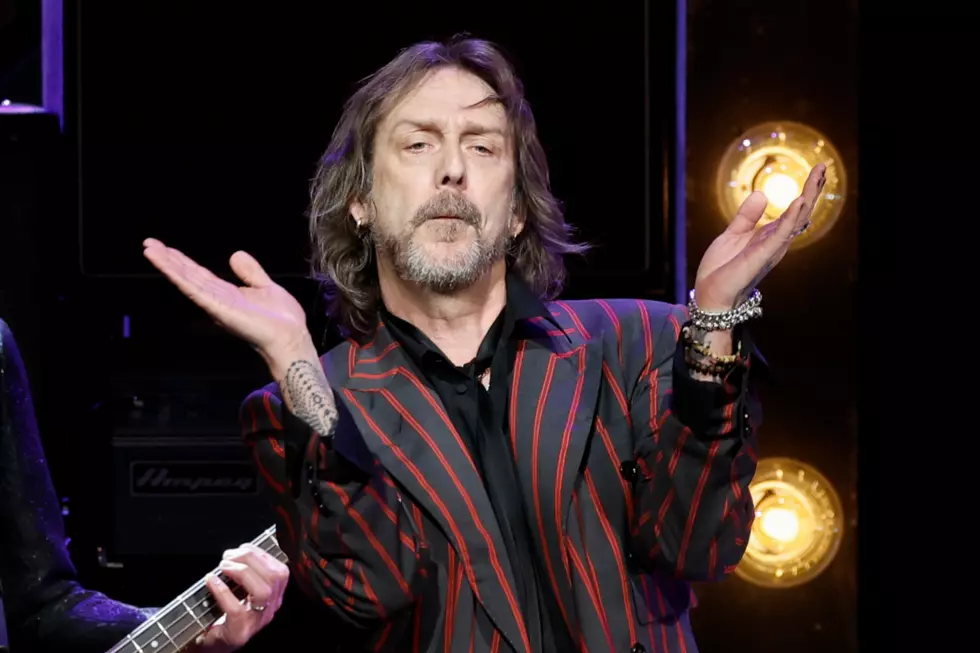

Drummer Steve Gorman Looks Back at Black Crowes’ Legacy: Interview

Former Black Crowes drummer Steve Gorman has spent the past few years immersed in revisiting the time he spent in the turbulent band.

He tells some of the best war stories from his experiences in a laid-back and lighthearted tone, often punctuating the memories with a weary laugh, as if to say, "I know how unbelievable this sounds." That's one reason he was hesitant to put his story down on paper. Friends would urge him to write a book, and he often replied, "Well, I would, but nobody would believe it."

By the time Black Crowes keyboardist Ed Harsch died in 2016, Gorman knew the time had come. He'd written a long eulogy to Harsch to read on his radio show and knew it was the bones of something bigger. He kept sketching out thoughts and eventually realized he was heading toward actually writing a book.

Something else was different too: "I can tell [you] right now that I never wanted to write an angry or bitter book about the Black Crowes," he told UCR. "Ed’s death removed all of that. It was a level of finality that I didn’t know I needed to get to. Once Ed died, I just felt, oddly, really appreciative and grateful for all of the positives that came from the band, and it just put everything into a really sharp relief."

Gorman found clarity and realized he's been "really pissed off" about how things had ended, but that time had passed. "I’m not angry anymore," he says now. "I can’t imagine it ending in any other way. The band was such a contentious existence on a day-to-day basis and that was all gone. I just thought, 'Fuck, man. Ed died. I’m really not going to feel good about going to my grave without telling my story.'"

Hard to Handle: The Life and Death of the Black Crowes is that story. In the second part of our conversation with Gorman, he talks about Harsch, the Black Crowes' legacy and some of the frustrations he faced as they moved through the '90s.

I found Ed Harsch to be one of the favorite characters that I was reading stories about in this book -- the word “character” used intentionally. But you also did a lot to really give me extra appreciation for everything he added to those records and songs.

He was never a guy who even thought in those terms about, “Man, no one noticed what I did!” That’s the furthest thing from Ed’s mind. But it’s certainly something when I look back, it’s just so crystal clear. I don’t say that to downplay anybody. Everybody contributed mightily. The thing I loved and will always love about the Black Crowes is when it was great, you had an all-hands-on-deck mentality and everybody was putting everything they had into a common feel and sound and mindset. When that was happening, that band was fuckin’ special. That’s the part about it that makes me sad to this day. There will always be a sadness that we couldn’t hang onto that. But I’m really glad it happened. If you had looked at me in 1987 and said, “This is what’s going to happen if you do this,” I’m signing up again, of course.

I found myself, pretty naturally, going back and listening to the albums as I was in the process of reading the book. When you were working on the project, how much time did you spend revisiting the records individually?

None.

Really?

There was a few times when I would hear songs in the car. Something would come up, either on my cloud or on Sirius, flipping channels. I was writing about the making of Amorica and I left the house to just drive for 20 minutes and clear my head and go get a cup of coffee. “Gone” came on the random play. I cranked it up and listened, and I was just like, “Holy fuck, man! That is a track!” It was like, “Holy shit, we were getting it!” It was really exciting. There was a couple of those little moments like that. But I didn’t go back and sit there and listen to things straight through at all. I didn’t need to. Those records, all of that music, it’s not like it’s ever in the back of my mind. It’s all very much in my skin.

Watch the Black Crowes' 'Gone' Video

You’ve talked about your linear memory, for better or worse. But hearing that, you bring some interesting context to each of these records with the stuff you write in the book, so to hear that is interesting. You spent so many years living with those songs and living with that music, it makes sense that you wouldn’t have had to go back to it all as any sort of a refresher.

The thing is, if I hear a Magpie Salute song or if I hear a Chris Robinson Brotherhood song, there’s a part of that song that will needle in my brain and it’s there for life. It’s not every song at all, and I haven’t heard all of the stuff they’ve released or even close to it, but I’ve heard enough where there will be a turn of phrase or a melody or a riff or a chord progression where there’s no question who wrote it, there’s no question that it’s like, “Oh, that’s something I’m supposed to do something with.” That’s Pavlovian.

Does that torture you at all to hear that kind of stuff and wonder what you could have done with it?

No, not at all. It tortures me that it happens. It doesn’t torture me, what might have been. There was probably a time in 2002 and 2003 where I would have denied that happened. Because I was like, “Fuck, why am I thinking about this?” It’s not a question of thinking about it, it’s just like I said, it’s Pavlovian. And it’s way better to acknowledge it and then move on than to pretend it’s not happening. Because for years and years, any idea that either one of those guys brought forward, I’m sitting right there playing along. I just got so attuned to how they do what they do. Which is not to say that if we got in a room that it would work, I’m just saying that it’s just muscle memory type of stuff for me. It’s like, if I smell a grape Nehi [soda], I’m at the first tee of the Hopkinsville Golf and Country Club. It’s the same thing.

Listen to the Black Crowes' 'Sting Me'

You’ve said that The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion is your favorite Black Crowes record. What is it about that album in particular for you?

I haven’t listened to it straight through in forever, but that was a brief period of time when that’s what everything about being in a band was supposed to be. We had a real swagger to our playing and there was such confidence. There were other times when we were fronting how confident we were. Southern Harmony was not that at all. It was just completely, "Oh, this is where we are now? Fuck right, yes sir!" On the heels of the way the Shake Your Money Maker tour had ended and then two months later, we’re knocking this album out, it just felt like, “Holy shit, that was all worth it.” It was everybody doing what they did best. That’s the thing: When the band played to its strengths, we were all generally in better moods, the shows were better, the records were better, the songs were better. I just felt like, when it was authentic, [it was at its best]. And then on the tour for Southern Harmony is when we truly found the ultimate essence of what the Black Crowes were at their best. From ‘92 into ‘96, that was us just being us, the best it ever was. We felt good, but that record, it was proof. “Oh, we just did that? Okay, we really are as bad-ass as we’ve been acting like we were.”

Watch the Black Crowes Perform Live

When I listened as a fan and also someone who was working in radio at the time when By Your Side came out, I would have termed that as a very confident record. So it was really interesting to hear all of the stuff that was going on behind the scenes at that point. I wouldn’t have guessed that.

It’s an interesting thing. I can’t talk about By Your Side without thinking about Band, the record that was lost right before it. I can’t think about By Your Side without thinking about Marc [Ford] and Johnny [Colt] and the fact that they were gone and that we were dumb enough to just keep going. We didn’t say, “Wait a minute.” It’s so basic now, two completely essential and key components in the band leave in the space of a week and we don’t immediately all just say, “Holy shit, what are we doing?” Like, stop this, who needs what? Let’s all get some help. That was never talked about or considered. We hinted at it. [But the feeling was], “We’ve got to make this work.” We felt cornered and we were wounded. And you know, a wounded animal is the most dangerous animal. We were operating on a complete flee-or-fight [feeling] and we decided to fight. So, By Your Side, it’s such a mixed bag of everything. The album itself, because we had just done a record that meant [so much] -- I knew that Band wasn’t possible. We couldn’t put Band out and tour behind it without Marc and Johnny. That didn’t make any sense, because that record was all about cohesion and that lineup. When they left, we were still trying to get Columbia to buy into this album that we’d already made. But the truth is, if we’d gone out and toured on that album with two new guys, it wouldn’t have worked. It wouldn’t have made sense.

When things splintered and different visions became battle lines, the commercial success dropped as well. So it wasn’t like we all got on the same page and then our career went in the toilet. It went hand in hand. In the ‘90s anyway, we were just too stupid to see any of this or at least admit what it all was. I felt it -- nobody else really gave a shit what I thought about that kind of stuff. It was just all about survival at that point by the time By Your Side came around. That being said, there are some tracks on that record that fuckin’ smoke. We had gone through all of this stuff and now we’re just going to play some really straight songs? I was back to a click track and I was like, “Fuck, piece of cake, man. Cool!” I hear from people all of the time they fuckin’ love that record. It was a necessary piece, and if it weren’t for that record and if it weren’t for a lot of things, it wouldn’t have led to Jimmy Page, all of these things. It’s just part of the story and it’s an interesting one.

Listen to the Black Crowes' 'Band'

Hindsight is always 20/20, but hearing you talk about the Band record you had laid down prior to that, when you go back and listen to that Band album now vs. By Your Side, you can hear what was lost by that stuff not coming out at that time.

I still say that two of the best things that we ever did were never released. Then when Band was released in 2006 as part of The Lost Crowes. I love Paul Stacey and I think he does great mixing, I don’t think that was really well done. It’s a hard record to mix, because it was all just live and with all of the bleed -- the rough mixes we left the studio with in ‘97, you were never going to top those. Any thought put into it would only kind of lessen them. So the [version] that’s on The Lost Crowes, I’m not a fan of, but the original rough mixes that we all walked home with in the spring of ‘97, I’ll put that next to Southern Harmony. I fuckin’ love it.

See the Black Crowes and Other Rockers in the Top 100 Albums of the '90s

More From Ultimate Classic Rock