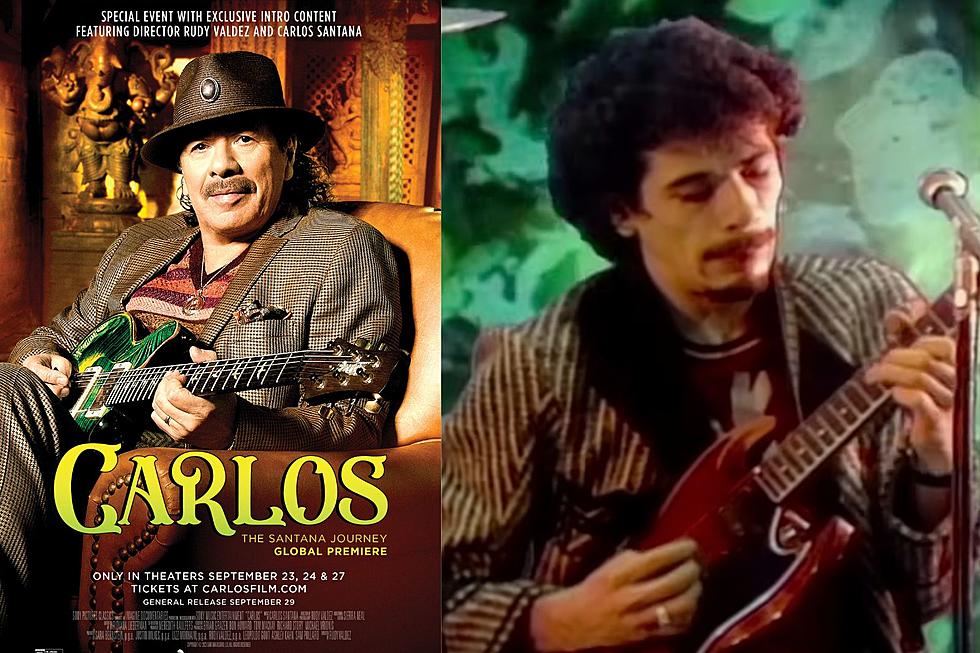

45 Years Ago: Santana Builds on its Woodstock Triumph with a Smash Debut

After their breakout performance before a certain mud-covered populace in upstate New York earlier that month, the August 1969 release of Santana's self-titled debut must have felt like a preordained hit. And big things happened, of course, as 'Santana' rose to No. 4 on the Billboard 200, pushed along by the rambuctious Top 10 hit 'Evil Ways.' But the path Santana took to this moment of overnight success was, like most, both long and winding.

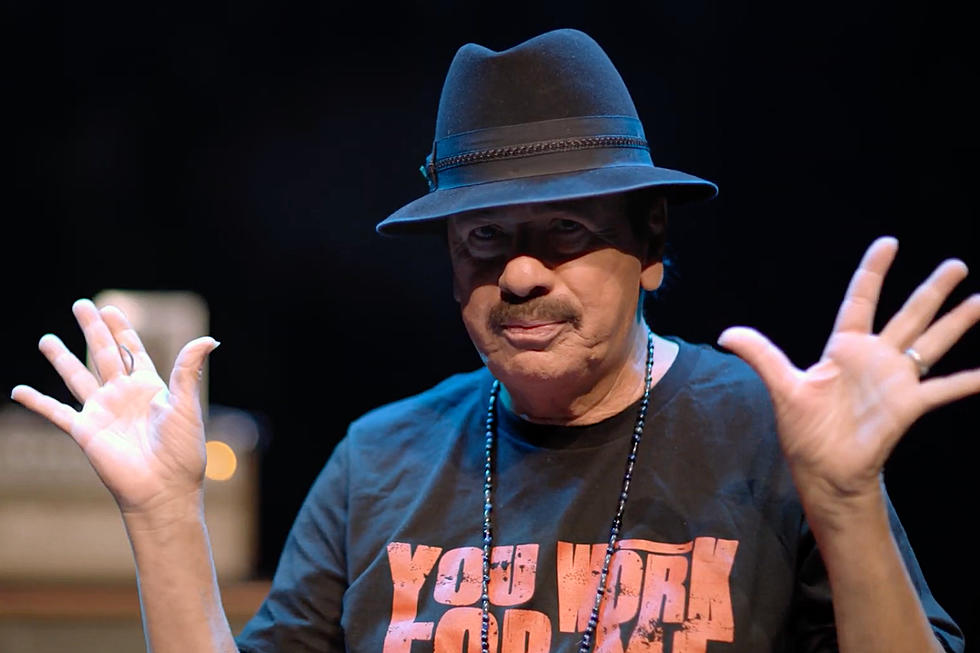

Namesake Carlos Santana began his career in the late '60s with a tight focus on the blues, and he admits that he might have stayed in that rut -- if not for a lineup that had only just recently rounded into its final form prior the sessions for 'Santana.' Early incarnations, which also included percussionist Michael Carabello and organ-playing vocalist Gregg Rolie, were more roots-focused, less inventive.

Still, Rolie had come on board with concrete ideas about what a music career should entail -- and he saw in Carlos a star on the rise. "The general idea of having your own and playing your own music and expressing yourself really appealed to me," Rolie told Rock Cellar last January. "Then I met Carlos and everything took off. We played stuff that nobody had ever done before."

Bassist David Brown joined in 1967, followed just before Woodstock in 1969 by second percussionist Jose "Chepito" Areas, who replaced early member Marcus Malone. Santana himself credits Michael Shrieve, who also joined in '69, as being the final piece of the puzzle -- and not just because of his jaw-dropping skills at the drums. Shrieve helped Santana dig deeper, to hear more, and that took the guitarist's music in an entirely different direction.

Shrieve “opened me up from being a very ignorant, lock mind and feel person," Santana told Guitar Player earlier this year. "If it wasn’t John Lee Hooker, Jimmy Reed or B.B. King, I didn’t want to hear about it. But Michael brought me a whole bunch of records by John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Django Reinhardt, Baden Powell and Wes Montgomery -- and he said to me: ‘You need to listen to this man, because this is you.’”

Shrieve, for his part, became so excited by the sounds they were making together that he reportedly turned down an opportunity to join the Jefferson Airplane, long before Santana rose to fame.

Through it all, Rolie was struck by Carlos' unique approach. Even as he absorbed a dizzying array of sounds, influences from all over the map, he always ended up with something entirely his own. "With Carlos, the best way to describe his playing is expressed by feelings. Carlos plays Carlos; he doesn’t play anybody else. He doesn’t go anywhere else," Rolie once told this writer. "Carlos has stuck to the roots of what he wants his guitar to sound like."

As such, the Santana band had taken the stage at Woodstock for the biggest show of their young musical lives simply bursting with confidence. "The most important thing one has to do -- whether you're playing Woodstock or a parking lot or the Grammys or Carnegie Hall -- is you have to present with love. Your brain and your heart cannot be somewhere else," Santana remembered more recently. "A real musician has to trust muscle memory; you have to know that your hands and fingers will go where they need to go. But at the same time, every note has to come from the center of your heart."

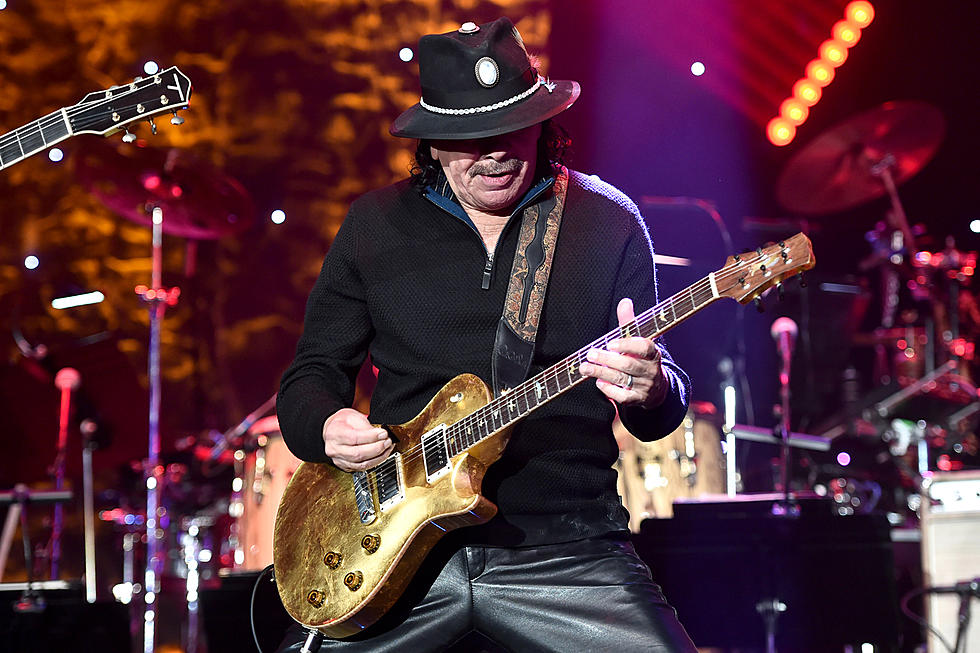

More earth-bound advice through the recording process which preceded that career-making appearance came courtesy of manager Bill Graham, who encouraged Santana to include a few conventional songs with their undulating mixture of jam-band excursions -- and his hunch was right. As much as their more entrenched Bay Area fans must have loved it when Carlos unleashed his liquid expressions of guitar ecstasy, we now know that the band's more compact, Rolie-sung 'Evil Ways' would ultimately streak up the charts.

The important distinction was that Santana had given nothing away in the bargain. That rhythm-driven song still sounded both uniquely like Santana, and utterly unlike anything else on the radio. At the same time, 'Santana' made room for long-form, often decidedly complex instrumentals like 'Waiting' and 'Treat'. Taken for granted in today's multi-cultural media melting pot, 'Santana' marked the big-bang of Latin rock. And the group would only build from there over a stirring three-album run through 1972 that included 'Abraxas,' 'Santana III' and 'Caravanserai.' The template, in no small way, was set here.

"It's amazing; within a year, everybody had congas and timbales -- the Rolling Stones, Sly Stone, Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis," Santana later recalled. "All we really did was integrate Tito Puente, Afro-Cuban musicians like Mongo Santamaria, into the blues that I loved."

Barely known before August 1969, within a few weeks, they were superstars -- with an emphasis on the plural. Santana was, back then, a collaborative event. Five of the nine songs on 'Santana' were credited to the entire band. Both 'Evil Ways' (written by Clarence "Sonny" Henry) and 'Jingo' (by Nigerian percussionist Babatunde Olatunji) were cover songs, but they were completely re-envisioned in this group's collective image. Santana and Rolie co-wrote 'Shades of Time,' and the two of them worked with Malone and the dearly departed Brown on 'Soul Sacrifice.' "One of the things about that original rhythm section," Shrieve once related, "was that everybody was so unique unto themselves, but somehow together it made a sound and groove like no other. It was true chemistry, and David had a lot to do with that sound."

Graham's influence could also be felt in the image used for the album cover, a Lee Conklin illustration that had been adapted from a concert poster used by Santana when they played Graham's Fillmore West. "You know, without Bill, many things wouldn’t have happened for Santana," Rolie said in an interview with Ultimate Classic Rock earlier this month. "It’s just really a fact. He got us on Ed Sullivan as well, Johnny Carson -- and, at the time, I didn’t really know that. It was afterwards that I really realized how much he had done for the band and for Carlos’ career."

Unfortunately, over the years, the Santana name brand came to mean less and less, as original members peeled off -- leaving the guitarist with a rotating group of faceless sidemen. By 1974's 'Borboletta,' Rolie and Neal Schon (an early '70s addition as second guitarist) had adjourned to form Journey, leaving only Areas, Brown and Shrieve from this classic lineup. Brown was on hand for 1976's 'Amigos,' and Areas returned for a pair of subsequent albums. But 'Inner Secrets,' released in 1978, found Santana surrounded by an entirely new group of faces, and so it went.

Ultimately, those lineups had little in common with the one that coalesced in 1969. As Rolie noted, "it was truly a band, not just him. It only became his after the third album." What was missing, thereafter, were communal triumphs like the debut-closing 'Soul Sacrifice,' a highlight of the Woodstock performance that was built upon one of Santana's earliest compositions. The song only took wing, Carlos has admitted, with the addition of Brown into the group.

It's of little surprise, then, that there is talk of a reunion featuring Santana, Rolie, Schon, Shrieve and Carabello -- with Benny Rietveld, a '90s-era Santana band member, filling in for the late Brown. "We were all very fond of each other and protective of each other, and I think we all really appreciated the diversity and what each of us brought to the table," Shrieve said of those early days. "Being in Santana was like being in a street gang, but the weapon was music."

More From Ultimate Classic Rock