The Complicated, Generation-Defining History of Woodstock

Some 500,000 people descended upon Max Yasgur’s farm on Aug. 15, 1969 in Bethel, N.Y., to take part in one of the most memorable spectacles of the decade. Through all the mud, the mayhem, and the music, Woodstock is still remembered as the greatest music festival of all-time.

It actually began the year before, however, almost 1,300 miles away in South Florida where Brooklyn native Michael Lang had organized the Miami Pop Festival. Afterward, Lang returned to New York where he was introduced to the vice president of A&R at Capitol Records, Artie Kornfield. The two men began to think up ideas for a new festival in upstate New York, similar to the one Lang had staged in Miami.

Just then, fate intervened in the form of a well-placed ad in the New York Times. Placed by a couple of venture capitalists, it read: "Young men with unlimited capital looking for interesting, legitimate investment opportunities and business propositions." Lang decided to pitch them on another music studio around Woodstock, NY, but found the pair unenthused with the idea. They did, however, express interest with their ideas about a music festival upstate. The four entered into a partnership called Woodstock Ventures.

Of course, based solely on his hippie attire, Lang didn't present like the savvy businessman that he was. He quickly set about extrapolating from the Miami budget, and selected the Winston Farm site in Saugerties, NY -- though, unfortunately, the farm’s owner had no interest in leasing his land for a festival. Finally in July, a mere month before they planned to kick things off, Lang was introduced to Yasgur, a dairy farmer from Bethel.

He'd ultimately do more than allow Woodstock Ventures to use his land. He also helped grease the skids with the local community, and paved the way for the organizers to receive the necessary permits. "Max was our savior," Lang would later write in ‘The Road to Woodstock.' The next month was a whirlwind of construction, booking, and advertising. Up to the final two days, organizers scrambled to get basic things like water and electricity pumped into the venue space. They were consistently hampered an array of unpredictable weather events, a freak fire that burned down the staff's living quarters -- and, already, by crowds of people.

It seems Lang's marketing campaign had worked a little too well. Having built up such a rudimentary infrastructure in such a short amount of time, Lang and his partners were left with only one option to prevent what could have been a disastrous riot. Just before the first day, all of the fences surrounding the stage site were torn down. Woodstock would now be completely and totally free.

Day One: Friday, Aug. 15

Woodstock was advertised to start at 4PM. The only problem was in finding someone willing to go onstage first. The plan had been for the L.A. rock band Sweetwater to kick things off, but they were still stuck in the snarl of traffic around Bethel. With nowhere else to turn, Lang approached Greenwich Village mainstay Richie Havens and asked if he’d go on. Havens was reticent -- his bass player hadn’t made it yet -- but he nevertheless he agreed.

Over the next two hours, Havens regaled the crowd with every song he knew, having been sent back on stage each time he tried to leave. Finally, he was left to simply vamp on his guitar and sing the word "freedom" over and over again. “I think the word 'freedom' came out of my mouth because I saw it in front of me," Havens later recalled. "I saw the freedom that we were looking for. And every person was sharing it, and so that word came out."

Sweetwater followed, and then Burt Sommer and Tim Hardin respectively. Ravi Shankar went on at 10:00PM, playing for a little over half an hour during a rainstorm before giving way to Melanie. The last two slots of the first day were pegged for two icons of the folk movement, Arlo Guthrie and Joan Baez.

A late start and time overruns had pushed Baez's closing set start time to nearly 1:00AM. Later, Baez said she was actually grateful for the early morning time. “It had been so long waiting and that’s one of the dynamics that can happen with that. I was all set to be dealing with stage fright and now it’s gotten so late I’m not going to bother. And I knew I was singing to a city.”

After a stirring rendition of 'We Shall Overcome,’ at 2:00AM, the first day of Woodstock was in the books. It had gotten off to a bit of a rocky start, but the performances and the behavior of the crowd exceeded anyone’s expectations.

But then the crowd, already massive, continued to grow.

Day Two: Saturday, Aug. 16

The second day of Woodstock began just after noon with a Northeastern psychedelic rock group named Quill, followed by Country Joe McDonald. (The promoters had found McDonald hanging out backstage and asked him to fill time to allow the next band, Santana, to get ready.) Rain from the previous evening had turned the massive field into a quagmire of mud and bodies. Speculation ran rampant that New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller would declare the site a disaster area.

This unkempt environment made the perfect setting for what became McDonald's career-defining moment -- a profane cheer that swept through the crowd. "I said, 'Give me an F,'" McDonald remembered in Lang's book. "And everybody turned and looked at me, and said, 'F.' Then I said, 'Give me a U.' And they yelled back, 'U!' And it went on like that. And I went on singing the song and they all kept staring at me. My adrenaline got really pumping.”

Santana, then still a month away from its debut album, received an invite by way of rock promoter Bill Graham, who had proven invaluable in helping book acts for the festival. Their incendiary Latin rock performance launched Santana toward super-stardom, but not without one small regret. “I was under the influence of LSD,” Santana has said. “The guitar neck, it felt like an electric snake that wouldn’t stand still. That’s why I’m making ugly faces, trying to make the snake stand still so that I can play it.”

John Sebastian, founder of the Lovin’ Spoonful, followed, then Keef Hartley Band, the Incredible String Band, Canned Heat and Mountain -- the latter of whom was performing before a live audience for only the third time ever. All of that was supposed to have prologue to the legendary Grateful Dead on tap next, but the legendary San Francisco jam band fell flat.

“The weekend was great, but our set was terrible,” Jerry Garcia later admitted. “We were all pretty smashed, and it was at night. Like we knew there were a half million people out there, but we couldn't see one of them. There were about a hundred people on stage with us, and everyone was scared that it was gonna collapse. On top of that, it was raining or wet, so that every time we touched our guitars, we'd get these electrical shocks. Blue sparks were flying out of our guitars.” The Dead’s set ended, perhaps appropriately, a half hour early with a set of blown amps.

But the evening was far from over. Creedence Clearwater Revival took the stage, playing for just under an hour to an increasingly drowsy crowd. "We were ready to rock out and we waited and waited and finally it was our turn ... there were a half million people asleep," singer John Fogerty recalled in the book 'Bad Moon Rising.' "And this is the moment I will never forget as long as I live: A quarter-mile away in the darkness, on the other edge of this bowl, there was some guy flicking his Bic, and in the night I hear, 'Don't worry about it, John. We're with you.' I played the rest of the show for that guy."

The evening wore on, with sets from Janis Joplin and Sly and the Family Stone. Sly didn't take the stage until almost 4:00AM “We just looked at each other, grabbed each other’s hands, and said, ‘Let’s just go do our thing and do it the best we can,’” Family Stone drummer Greg Errico remembered. “Fortunately by about the third song, we got everybody to come out of their bags and tents. By the third or fourth song there was unbelievable energy being transferred between the stage and the audience. When you watch the movie, you can feel it. It’s funny looking back and knowing it was 4:00AM. three days into the festival.”

As the sun was threating to rise, it was The Who's turn. But then, midway through, they were interrupted by Yippie movement leader Abbie Hoffman -- who’d jumped onstage in an attempt to make the audience aware of the plight of imprisoned poet, John Sinclair. As Hoffman began his speech he was cruelly interrupted by a whack from Townshend’s instrument. “I knocked Abbie aside using the headstock of my guitar,” Townshend remembered in his book 'Who I Am.' “A sharp end of one of my strings must have pierced his skin because he reacted as though stung, retreating to sit cross-legged at the side of the stage.”

Jefferson Airplane wouldn't take the stage until 8:00AM. It had been a grueling wait. “[We] stayed onstage all night – no bathroom – taking lots of drugs,” Grace Slick said. “I’m surprised we were able to perform at all!”

Day Three: Sunday, Aug. 17

The first act on the next day's slate was the show-stealing Joe Cocker. “We were kind of lucky because we got onstage real early,” he said. “It took about half the set just to get through to everybody, to that kind of consciousness. You're in a sea of humanity and people aren't necessarily looking to entertain you. We did 'Let's Go Get Stoned' by Ray Charles, which kind of turned everybody around a bit, and we came off looking pretty good that day.”

Country Joe then followed for his second appearance of the festival, this time with his band the Fish. They were followed by Ten Years After and then the Band, whose homey brand of proto-Americana got lost in the hoopla. “I remember I looked out there, and it seemed as though the kids were looking at us kind of funny," Robbie Robertson explained in the book ‘Woodstock: Three Days that Rocked the World.' "We were playing the same way we played in our living room, and that might have given the impression that we weren’t up for it.”

Johnny Winter and Blood, Sweat and Tears then set the stage for the long-awaited debut of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. Their entrance was awe-inspiring, Graham Nash remembered in his book ‘Wild Tales.’ “It was pretty wild. We flew up along the Hudson River and then over this … sight!” he wrote. “David [Crosby’s] description of it was the best. He said it was like flying over an encampment of the Macedonian army. There were a lot of people there. It was more than a city of people -- it was tribal. Fires were burning, smoke was rising, a sea of hippies clustered together, shoulder to shoulder, hundreds of thousands of them.”

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band took the festival stage next, then Sha Na Na. But by then, the third day of Woodstock was over. There was only one act to go.

Day Four: Monday, Aug. 18

Jimi Hendrix was always going to be the Woodstock headliner. “For what I thought would be the midnight close of Sunday night, it had to be Hendrix,” Lang wrote in his book.

Hendrix had, of course, headlined Lang’s earlier Miami Pop Festival, but in the meantime, his career had taken off. As he'd gotten more famous, his band's lineup had shifted, too -- going from a tough trio to a large newly formed ensemble, as seen at Woodstock. It seemed, by 9:00AM on Aug. 18, that they may have outnumbered the fans -- which were estimated to have numbered only 40,000 by then. That didn't stop Hendrix from unleashing one of his longest sets ever, though -- because of all of the new faces in his band -- it was also one of his more rough-edged.

Noticing that the thinning crowd, Hendrix stepped to the mic to say, “You can leave if you want to, we’re just jamming, that’s all. OK? You can leave or you can clap.” And with that, he launched into a medley that would include his unforgettable take on 'The Star Bangled Banner.' “It was the most electrifying moment of Woodstock, and it was probably the single greatest moment of the '60s," rock journalist Al Aronowitz wrote in the book ‘Room Full of Mirrors.’ "You finally heard what that song was about, that you can love your country, but hate the government."

After four more songs, Woodstock concluded at 11:10AM.

Aftermath

Woodstock moved into mythical status, however, through the dual media of film and audio. In his gut, Lang knew that the event had to be captured -- and he put a premium on making it happen, hiring director Michael Wadleigh to film the festival in its entirety. On the audio end, Lang brought in producer/engineer Eddie Kramer who’d already worked with acts like Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin.

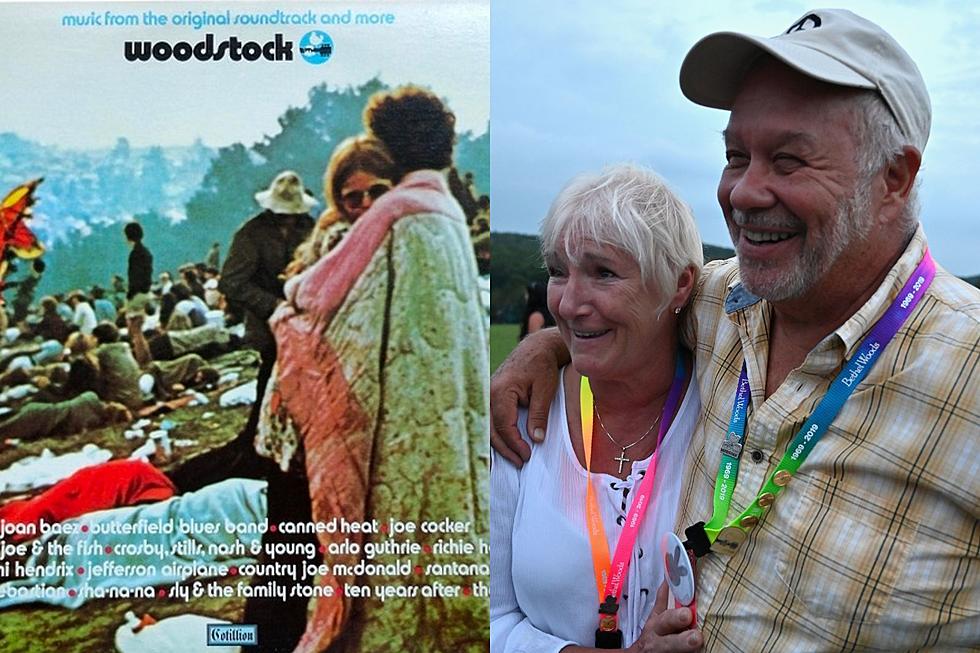

‘Woodstock’ made its onscreen debut on March 26, 1970 and became a runaway success. Beginning with a modest budget of just $600,000 the film went on to net some $50 million. The three-album soundtrack was a smash as well, replacing the Beatles' final album ‘Let It Be’ at the No. 1 position on the Billboard 200. That said, Woodstock still nearly ruined the men who had dared put it on in the first place. “It was determined that Woodstock Ventures was $1.4 million in the hole,” Lang explained. He and Kornfield were forced to accept a buyout from their other partners.

In the end, Woodstock began more than a money-making venture, however. Even more than an event. “For those who passed through it, Woodstock was less a music festival than a total experience, a phenomenon, a happening, high adventure, a near disaster and, in s a small way, a struggle for survival," a Life Magazine writer once said. "Casting an apprehensive eye over the huge throng on opening day, Friday afternoon, a festival official announced, 'There are a hell of a lot of us here. If we are going to make it, you had better remember that the guy next to you is your brother.' Everybody remembered. Woodstock made it.”

10 Artists You Didn't Know Played Woodstock

Watch Crosby Stills & Nash Perform 'Marrakesh Express' at Woodstock

More From Ultimate Classic Rock