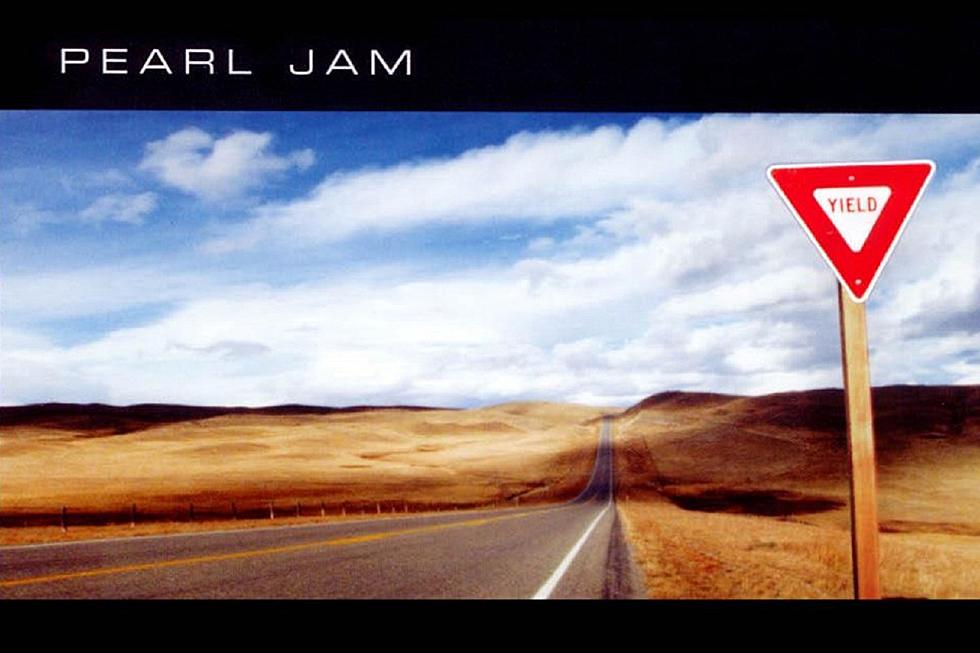

When Pearl Jam Decided to ‘Yield’ to Maturity

In the years after Pearl Jam became a blockbuster band, the group became embroiled in high-minded and self-protective battles. They stopped playing venues associated with Ticketmaster, whom they sued. They stopped making music videos. They stopped giving interviews. And they nearly stopped being a band.

But with maturity often comes some measure of wisdom and acceptance. In the back half of the ’90s, Pearl Jam began to soften some of their hardline stances, not as a betrayal of their ethics but as a method to focus on the music. They ceased putting up stop signs and learned to yield – which became the name of the rockers’ fifth album.

“I think the title Yield has to do with maybe being more comfortable within ourselves, with this band,” guitarist Mike McCready said in 1998. “Whereas the earlier records were like Vs. – we were kind of reacting to the storm of press and craziness that was happening. Now, we’re all a little bit older and a little more relaxed and maybe just kind of yielding to those anxieties and not trying to fight it so much.”

Some of that comfort came in the form of increasing collaboration within Pearl Jam. Near the end of the recording process for 1996’s No Code, frontman Eddie Vedder spoke frankly to his bandmates (McCready, guitarist Stone Gossard, Jeff Ament and drummer Jack Irons) about wanting the band to be more democratic, in terms of the lyrical and conceptual burden, on the next record. Vedder would remain the primary lyricist, but yearned for some of that weight to be alleviated.

The guys responded to the request, with Irons contributing the music and lyrics for one track (“Untitled”), Gossard writing two (“No Way,” “All Those Yesterdays”) and Ament also penning two (“Pilate,” “Low Light”) – which were the bassist’s first lyrics written for a Pearl Jam record. Unlike the band’s previous four albums, Yield would find Vedder singing words which did not originate with him.

“I think the fact that everybody had so much input into the record, like everybody really got a little bit of their say on the record,” Ament told MTV, “and I think because of that, everybody feels like they’re an integral part of the band.”

That shift meant that the members of Pearl Jam came to their 1997 sessions at Seattle’s Studio Litho and Studio X with more concrete musical ideas and more complete songs. Producer Brendan O’Brien noticed the change between the rough-hewn “we’ll figure it out as it goes” aesthetic of No Code and the bolder, hookier material that would fill Yield.

“I remember there was a concerted effort to really put together the best, more accessible songs they possibly could,” O’Brien told Spin in 2001.

Listen to Pearl Jam Perform 'Given to Fly'

Many of the tracks were Pearl Jam’s most aggressive in a while, from the chugging kickoff of “Brain of J.” to the glimmering distortion of “MFC” to Vedder’s maniacal howl on “Do the Evolution.” The album’s lead single, “Given to Fly,” would earn comparisons to Led Zeppelin – albeit the gentler, folksy “Going to California” and not something Hammer of the Gods-like.

“Given to Fly,” with its steady rise of melody and power, became the band’s biggest hit in a couple of years, going to No. 21 on the Bilboard chart. It also encapsulated the balance discovered by a more mature Pearl Jam on Yield. This album contained a synthesis of arena and punk rock influences, melodies and experiments, blazing guitar and strummed whispers. And it all seemed so comfortable.

The lyrics reinforced that comfort and maturity. With all members now in their 30s, they took a more contemplative but positive look at life’s struggles. Vedder and pals drew from literature (Charles Bukowski, Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael) as well as more personal feelings about the future (“Low Light”), interaction (“In Hiding”) and the power of love in the face of struggle (“Given to Fly”).

Pearl Jam put out Yield on Epic Records on Feb. 3, 1998, selling hundreds of thousands of copies in the first week of release, although the album was kept at No. 2 on the U.S. charts by the Titanic soundtrack. The band’s fifth album was the first to not top the Billboard chart, although it gradually went platinum and eventually outsold No Code.

Yield was greeted with enthusiastic reviews, many of which hailed the record as something of a return to form. The record’s commercial success was also aided by Pearl Jam’s willingness to actually promote this album (which had been lacking on past releases) with press interviews, a music video (co-directed by Spawn creator Todd McFarlane and Batman: The Animated Series director Kevin Altieri) and an enormous tour that took the band to Australia and all over North America.

However, between the Oceanic portion of the trek and the Stateside dates, drummer Irons decided that the big tour was too much for him and he departed the band after about four years behind the kit. Pearl Jam recruited Matt Cameron (of the recently disbanded Soundgarden) to play the North American shows and he’s been part of the group ever since.

Cameron’s first run with Pearl Jam was recorded for the band’s first-ever concert album, Live on Two Legs, which was released in the fall of 1998 and featured hits, fan favorites and tunes from Yield. The new stuff fit comfortably amongst the steadily growing Pearl Jam oeuvre.

“Yield was a superfun record to make,” Ament reflected. “And so much of it was Ed kind of sitting back; we worked on all of our songs before we worked on any of his stuff. That was a huge thing.”

Top 100 '90s Rock Albums

Gallery Credit: UCR Staff

What Classic Rockers Said About Grunge

More From Ultimate Classic Rock