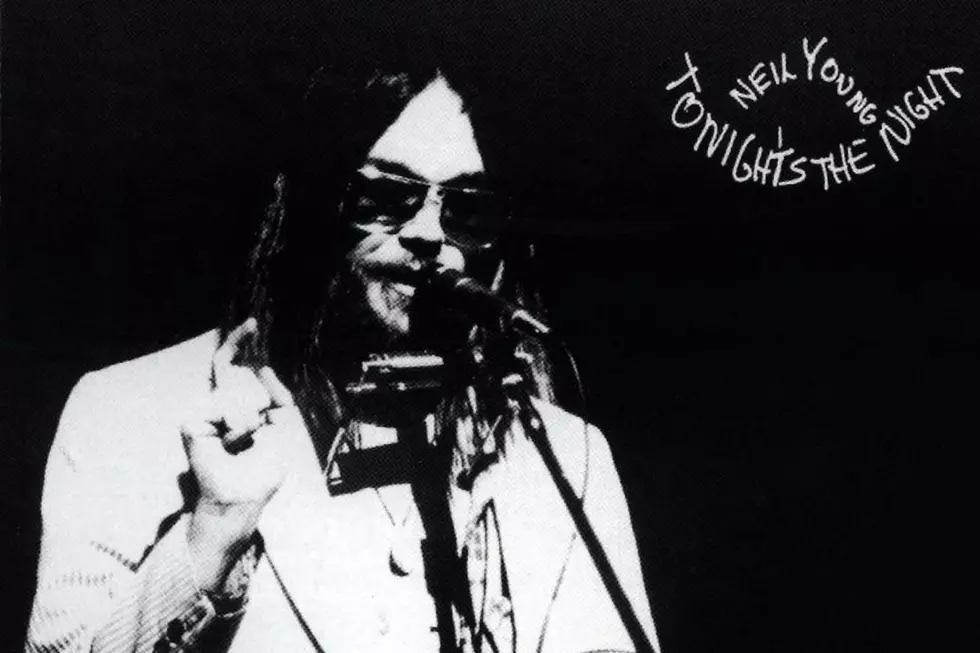

How Fate Fed Into Neil Young’s Mournful ‘Tonight’s the Night’

Like he would do so many other times in his long career, Neil Young followed his soft, introspective 1972 album Harvest with a loud, angry work. But 1975's Tonight's the Night developed more out of circumstance than design. And the path to Tonight's the Night wasn't so clear-cut.

In between the two works, both milestones in Young's catalog, the singer-songwriter released On the Beach, a polarizing record from 1974 that welded both noise and cynicism to some more lyrical and meditative moments. But that LP was recorded after Tonight's the Night, which sat in the vaults for almost two years. Young also put out a live album, Time Fades Away, and a soundtrack, Journey Through the Past, between Harvest and Tonight's the Night.

But for all intents and purposes, Tonight's the Night is the mellow, acoustic Harvest's follow-up. And after his only No. 1 album – Harvest remains one of his most popular records – the abrasive, deadly Tonight's the Night stands in stark contrast. But it wasn't supposed to be like that. Tonight's the Night wasn't even supposed to happen.

After Harvest, his fourth solo LP and commercial breakthrough, Young started working on a record much in the same acoustic style. Some of the songs were new, others were leftovers (one of them, "Lookout Joe," ended up on Tonight's the Night). But, as he's done on many other occasions during his long career, Young put the project on hold and moved on to something else.

Tonight's the Night's dozen tracks were patched together from a handful of different sessions, spanning a 1970 concert date to a home recording from December 1973. But the bulk of the material was recorded on Aug. 26, 1973, in Hollywood, during one whirlwind session that was quickly assembled following the drug-related deaths of two of Young's friends: roadie Bruce Berry and Danny Whitten, guitarist in his occasional backing band Crazy Horse.

Whitten, who was also one of Crazy Horse's prime songwriters (he wrote "I Don't Want to Talk About It," which Rod Stewart later made popular), died of a heroin overdose on Nov. 18, 1972. Berry – who served as a roadie for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, as well as the artists on their solo outings, and who was the brother of Jan & Dean's Jan Berry – also died of a heroin overdose, on June 4, 1973.

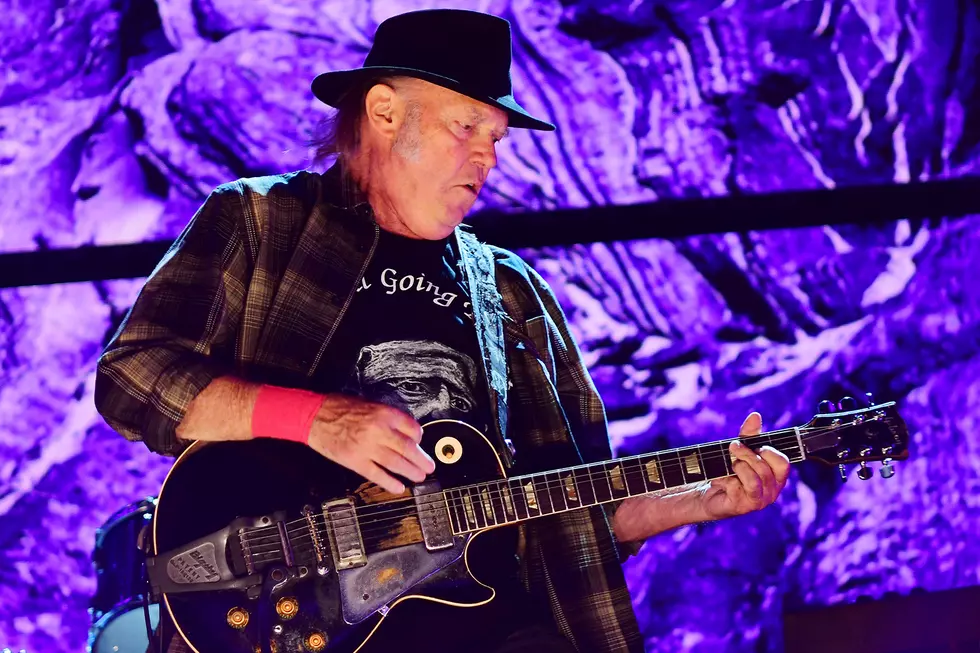

Two months later, Young and a band (which he called the Santa Monica Flyers) made up of Young associates Ben Keith and Nils Lofgren, as well as Crazy Horse's Ralph Molina and Billy Talbot, went into the studio to record a batch of new songs written in the wake of their deaths.

Listen to Neil Young's 'Tonight's the Night'

And like the lyrics to many of the songs, Young's delivery and playing was raw, angry and scarred. This was more than just a cathartic reaction to the senseless deaths of two friends; it was about coming to terms with loss, grief and despair in a world that was filled with it (both Vietnam and Watergate were part of the nightly news when Tonight's the Night was recorded).

Young tries to make sense of it all on songs like the title track (which bookend the album in two different versions), "Roll Another Number," "Albuquerque" and "Tired Eyes." "Come on Baby Let's Go Downtown,' penned by Whitten and recorded with Crazy Horse at the Fillmore East in March 1970, even features the late guitarist as both a tribute to him and as a commentary the LP's theme.

It wasn't what Young's record company was expecting after Harvest. And it sure wasn't something they felt would connect with the artist's new fans, who undoubtedly wanted more acoustic guitars, pretty harmonies and maybe a harmonica or two. The exposed nerves and seething rage tearing through Tonight's the Night made it a difficult listen, no matter where you entered. (And according to Young's dad in his book, Neil and Me, there's even another more despairing version of the LP sitting in the vaults.)

Young knew this, and it's one of the reasons the record sat unreleased for almost two years before it was finally sent to stores in June 1975. The rock press almost immediately hailed it as a masterpiece, a work of emotional release on par with John Lennon's Plastic Ono Band.

The record-buying public, however, didn't feel the same way. Journey Through the Past and On the Beach had already alienated many of the new fans who came in after Harvest; Tonight's the Night did little to bring them back, stalling at No. 25, Young's worst showing, not counting the Past soundtrack, since 1969's Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. Four months later, Young and Crazy Horse regrouped for Zuma, which also struggled its way to No. 25.

Besides the emotional torrent Young unleashed on Tonight's the Night, the record stands as one of the most defining albums in his relentless zigzagging between soft works and hard ones, acoustic LPs and plugged-in records, kinda commercial efforts and off-beat, what-was-he-thinking? concept albums. It was partly tragic fate that brought Young to Tonight's the Night. But in the end, he probably would have gotten there anyway, one way or another.

Neil Young Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock