50 Years Ago: ‘Monty Python’s Flying Circus’ Takes First Flight

It took the bedraggled castaway 52 seconds to wade out of the sea, collapse on the sand, crawl towards the camera and say: “It’s…” before the opening credits rolled. So began the iconoclastic experience known as Monty Python’s Flying Circus on Oct. 5, 1969.

What followed was a half-hour of mind-stretching comedy, including Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart presenting a series of famous deaths, an Englishman teaching Italian to Italians, an animated advert for Whizzo Butter, Pablo Picasso painting live on a bicycle, composer Arthur “Two Sheds” Jackson’s lack of a second shed and the most deadly joke in the world, amid a series of dying pigs.

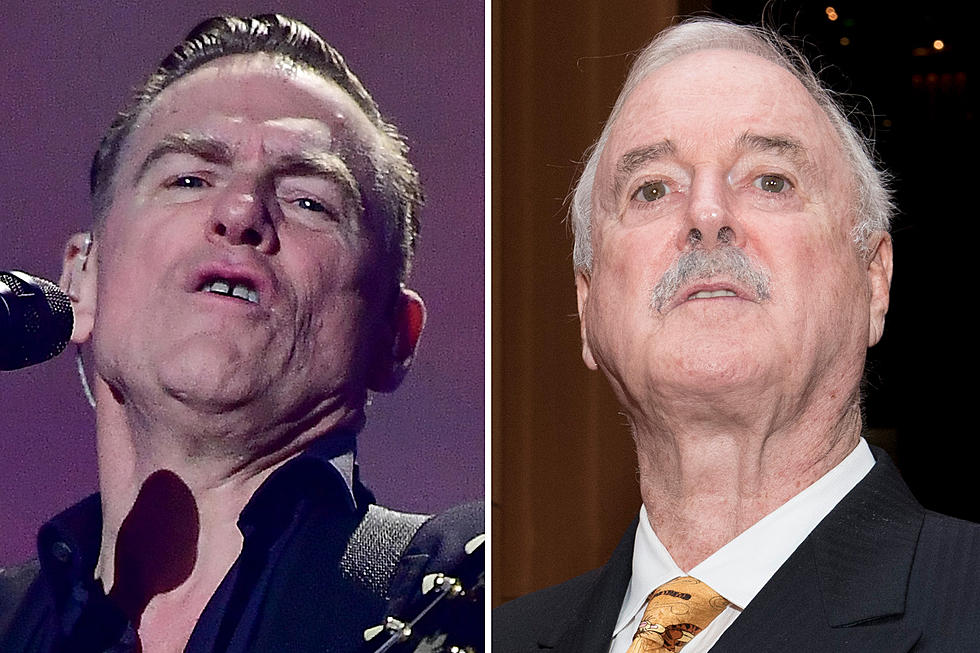

Very much a product of its time and geography, the comedy created by Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Eric Idle, Michael Palin, Terry Jones and Terry Gilliam grew out of Britain’s post-war years. It had its roots in the nation’s class system, where those regarded as “betters” often appeared to be worthy only of scorn. It was also fueled by the comedy of war survivors such as Spike Milligan, who sought to underline the sheer nonsense of being told to behave while waiting to die on command. The cultural turmoil of the ‘60s had also played a part, of course.

The result was a show that poked fun at the structure of society, while also being attractive in a surreal and silly level. The fact that it was produced by the BBC – a bastion of class structure – made it all the funnier.

Series 1, Episode 1 had been filmed a month before its broadcast, and was the first of 45 over four seasons. It was titled “Whither Canada?” – one of the names the group had wanted to use for the show itself, along with Ow! It's Colin Plint!, The Toad Elevating Moment and Owl Stretching Time. They’d settled on the idea of Monty Python as an untrustworthy entertainments agent and a First World War fighter squadron to create the name they went with.

“From the very beginning, Monty Python's Flying Circus demonstrated quite clearly that the group's six members were after something quite uncategorizable,” a feature on the show website reported. One of the sketches that had created the Python ambition was one about sheep in trees, which was rejected by David Frost’s The Frost Report. Jones recalled: “[Cleese]’s thing was always, 'The great thing about Python was that it was somewhere where we could use up all that material that everybody else had said was too silly.'"

From the outset, the group were as enthusiastic about performing as they were with writing. “Everybody wanted to go out there and put the dress on or whatever,” Palin said. “I rarely heard instance where someone said, 'Well, I don’t want to do that.' The great thing was, because we were all brought up in the university cabarets, to get out there and show your own material was part of it. Writing was merely 50 percent; the other 50 percent was the performing of it."

By nature rather than design, Chapman and Cleese wrote together, as did Palin and Jones; while Idle and animator Gilliam tended to operate solo. They’d come together and attempt to “sell” their sketches to the rest of the team, and those which received the most votes made the cut.

"I think our budget was £5,000 a show," Jones recalled. "It had been kind of a tight operation. Everything was planned very rigorously. We'd do the outdoor filming for most of the series before we started shooting the studio stuff. We had to write the entire series before we even started doing anything, because we'd be shooting stuff for show 13, show 1, or show 2 while we're in one location, so that while you're at the seaside you can do all the seaside bits."

The response to the first episode was polite but understated, although the Pythons were quickly regarded as “intellectuals’ darlings,” Palin noted. Cleese reflected: “I suspect you would probably get to show 9 or 10 of the first series before anybody was really writing that something remarkable was happening… A few people got it right away. But critics on the whole did something that they do when they're insecure: they describe what the show was like without really committing themselves to a value judgment.”

In a retrospective review, A.V. Club writer Zack Handlen argued that Python had indeed stood out from the very first show. “What gets me every time I watch this episode… is how unapologetic it is. How weird and manic and punk the show is from the very first frame, like it’s not so much a television program that was planned and scripted and rehearsed, as it is the end result of a group of lunatics seizing control of some cameras and costumes and holding the studio hostage until the police arrive.

“[T]here are a number of scenes with clear beginnings and middles. Some of them have endings. … [I]t’s worth nothing that the pilot does not try and hold our hands.” He added: “There have been many sketch shows in the wake of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and nearly all of them owe something to this one.”

Monty Python’s Flying Circus finally landed in the U.S. in 1974, around the time the show ended. (Cleese had left before the six-episode fourth series, but the resulting change in format to longer plot lines heralded their progression into movie-making.) PBS station KERA in Dallas was the first to broadcast, followed by ABC the following year. However, the network had decided to edit the episodes, losing the Pythons’ original intentions in the process. A lawsuit led to the comedians retaining control over later U.S. broadcasts, and also to recovering rights from the BBC.

The first season secured three BAFTA nominations and won two special BAFTA awards – one for production, writing and performance, the other for Gilliam’s palate-cleanser animations. Idle said later that he regretted how the rebellious Python spirit didn’t seem so rebellious for long. “Once when filming, a British middle-class lady came up and said, 'Oh, Monty Python, I absolutely hate you lot,’” he recalled. “And we felt quite proud and happy. Nowadays I miss people who hate us; we have sadly become nice, safe and acceptable now, which shows how clever an Establishment really is, opening up to make room inside itself.”

The Best Rock Movie From Every Year: 1955-2018

More From Ultimate Classic Rock