How Mick Jagger and Pink Floyd Could Have Been in a ‘Dune’ Movie

The first serious attempt to bring Frank Herbert's Dune to the screen nearly had music by Pink Floyd and Mick Jagger in a key role.

Following the mid-'70s success of avant garde movies El Topo and The Holy Mountain, cult writer-director Alejandro Jodorowski was given the opportunity by French producer Michel Seydoux to make any movie he wanted. Jodoroski chose Dune, even though he hadn't yet read the novel. (“I have a friend who [told] me it was fantastic,” he said.) Seydoux bought the film rights from Planet of the Apes producer Arthur P. Jacobs, whose own plans hadn’t gone far.

Within months of his appointment, a far-reaching plan for an adaptation ranging anywhere from 10 to 20 hours was underway. Jodorowski had no intention of making a feature that was faithful to Herbert’s book; instead, he had a far weightier and personal proposition. He wanted to tell the story of a messiah for the psychedelic generation, and to create the effects of an LSD trip without anyone actually taking any drugs.

“I wanted to create a prophet to change the young minds of all the world. Dune would be the coming of a god – an artistic, cinematic god,” he explained in the 2013 documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune.

He got to work with the pre-production budget. He hired the artists H.R. Giger, Gene “Moebius” Giraud and Chris Foss, each of them tasked with creating a different visual aspect of the Dune universe. Dan O’Bannon was to oversee the visual effects. The director told spaceship designer Foss, “I wanted jewels, machine-animals, soul-mechanisms ... womb-ships, antechambers for rebirth into other dimensions ... whore-ships driven by the semen of our passionate ejaculations ... humming-bird ornithopters which fly us to sip the ancient nectar of the dwarf stars giving us the juice of eternity ... caterpillar-tracked hot rods so vast that their tails would disappear behind the horizon ... machines greater than suns wandering crazed and rusted, whimpering like dogs seeking a master ... thinking wheels hidden behind meteorites, waiting, camouflaged as metallic rocks, for a drop of life to pass through those lost galactic fringes to slake thirsty tanks with psychic secretions.”

Giger later spoke of the first commission he’d been given for the movie, that of creating Castle Harkonnen, which he called “a symbol of intemperance, exploitation, aggression and brutality” that was built of “jagged bones and excrement.” He added: “The only link with the outside world is a drawbridge which can be lowered like an enormous penis to admit visitors. The main gate is only an entrance, never an exit, for it has barbs like sharks’ teeth which prevent anyone from turning back. The two walls of the drawbridge can be brought together hydraulically, crushing visitors who are hostile to the castle. … Every visitor is materially or spiritually exploited (as I was for this film project).”

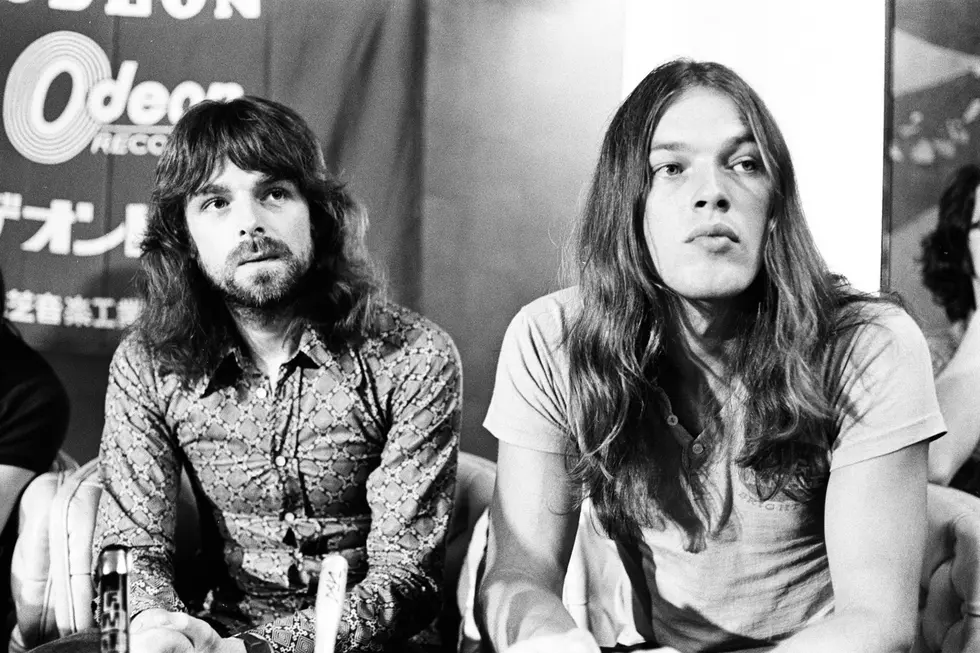

Original contributors to the soundtrack were to include prog bands Magma and Henry Cow plus composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. Then, Pink Floyd were signed to cover the majority of the music, with a double album expected. (Hans Zimmer’s take on Floyd’s “Eclipse” features in the trailer to the 2020 Dune movie.)

His casting was equally ambitious. Salvador Dali was to play Emperor Shaddam IV at a fee of $100,000, to which Jodo agreed, for only an hour of work. Orson Welles was to play Baron Harkonnen and Mick Jagger would appear as Feyd-Rautha, the same role that Sting played in David Lynch's 1984 version. David Carradine (Duke Leto) and Gloria Swanson (Reverend Mother Mohiam) were among other leading roles, with Jodo’s son Brontis cast as Paul Atreides.

The art team put together a complete storyboard of what they planned to put on screen, with lavish illustrations of the spacecraft and structures needed. Everything was assembled into a large, thick book, of which around 20 copies were made. Jodo set off to sell the project to a movie company, but no one took him up.

Among the criticisms leveled at the project were its scale, the fact that the story promoted the concept of following a charismatic leader while the book argued against it, and the argument that many of the things Jodo wanted to achieve on screen weren’t possible at the time. However, there’s potentially another reason – while moneymen were impressed with what they were shown, they may have been far more cautious about risking their cash on Jodo himself. Seydoux, who’d backed Jodo all the way and accompanied him on the fundraising trip, remarked, “Everything was great except the director."

Perhaps Jodo’s comments about actually raping actress Mara Lorenzio during the production of El Topo made it difficult for the mainstream to accept him. “After she had hit me long enough and hard enough to tire her," he said in a 1972 book about the film. "I said, ‘Now it’s my turn. Roll the cameras.’ And I really… I really… I really raped her. And she screamed. Then she told me that she had been raped before. You see, for me the character is frigid until El Topo rapes her. And she has an orgasm.”

In the 2013 documentary he described what he’d done to Herbert’s book as a similar sexual assault: “When you make a picture, you must not respect the novel. It’s like you get married, no? You go with the wife, white, the woman is white. You take the woman, if you respect the woman, you will never have child. You need to open the costume and to… to rape the bride. And then you will have your picture. I was raping Frank Herbert, raping… But with love, with love.”

With no takers, work was abandoned after $2 million had been spent on pre-production (the estimated completion cost was $15 million, compared with George Lucas spending $11 million on Star Wars). But Jodo’s Dune found a future of its own – his four “spiritual warrior” artists went on to create Alien. In the documentary a number of industry professionals testify that their work on Dune went on to influence Star Wars, The Terminator, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lynch’s Dune movie and The Fifth Element, among others. Jodo and Moebius went on to create The Incal graphic novel series, which also made use of the abandoned work.

Frank Pavich, who directed the documentary, said that he’d personally seen the storyboard sketches that he could identify as having appeared in other movies. “[W]e were kind of discovering it as we were going along, and they were these amazing revelations that we would come across,” he said.

He added: “[P]eople laugh at that… a 20-hour movie, who’s going to watch 20 hours? But how many people do you know that sit at home on a weekend and binge-watch an entire season of a TV show? I think people are looking for longer narrative, a longer story that they can become completely immersed in. And maybe that’s what he was going for. So it stopped at this kind of perfect moment of closure with that book. And maybe that’s as far as it was supposed to go.”

Jodo himself blamed the movie companies for refusing to accept a story that wasn’t “enough Hollywood,” insisting: “Almost all the battles were won, but the war was lost. The project was sabotaged in Hollywood.”

Perhaps that didn’t upset Herbert too much, although he’d said he had an amicable relationship with the director. But while taking part in promotional appearances for Lynch’s Dune, the author described himself as happy with the version of his story that had made it onto screens, and added: “Dino [de Laurentiis] called me… and said that he had hired David Lynch. And this was after a couple of, um, well, I think they would have been disasters! And David knows why.”

Watch ‘Jodorowsky’s Dune’ Trailer

The Stories Behind 19 Trippy Pink Floyd Album Covers

More From Ultimate Classic Rock