How Frank Zappa’s ‘Mothers of Prevention’ Responded to the PMRC

In the first four-and-a-half minutes of the 1995 reissue of Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention, variations on the phrase "I don't care" are repeated more than 30 times. But he might have been a bit defensive.

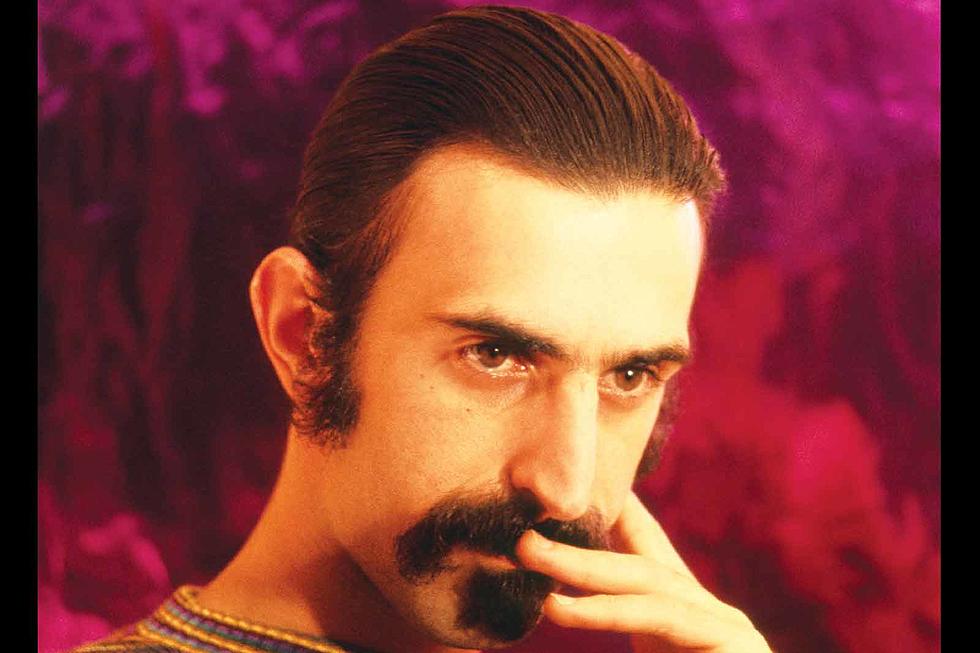

Frank Zappa cared about a lot of things. He was an exceptional businessman who wasn't above publicly shaming anyone who put his livelihood at risk. He cared about serious music, too, a fascination that went all the way back to his childhood discovery of Edgar Varèse. He cared about innovation and technology: Zappa was an early adopter and advocate of the Synclavier, one of the first digital synthesizers.

But above all Zappa's life's work reveals two consistent concerns: bullies and First Amendment issues. Frank Zappa was a true iconoclast, ready to burst political, religious and pop culture bubbles with a wave of his baton. The only thing Zappa seemed to hold sacred was his individuality. Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention, released Nov. 21, 1985, is the great big raspberry atop a then-nearly 20-year career of tilting at windmills.

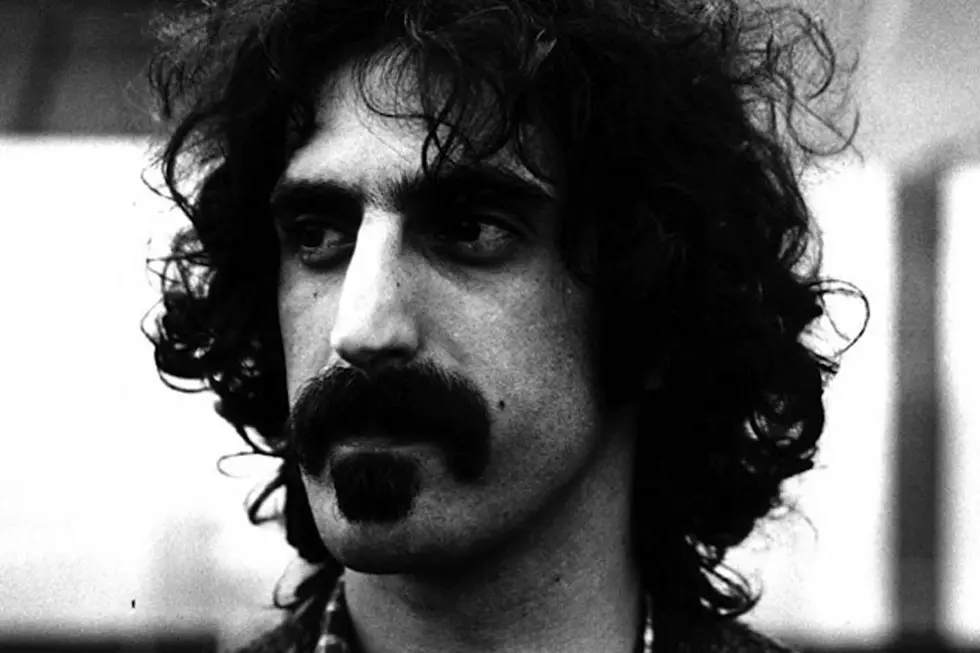

To understand Zappa's passion regarding free speech, we have to make a side trip to 1965 in Cucamonga, California, "a blotch on a map, represented by the intersection of Route 66 and Archibald Avenue," as the composer describes it in his autobiography, The Real Frank Zappa. It was a bow-ties-and-crew-cuts kind of town located in the desert outside of Los Angeles – an unlikely place for young Frank Zappa set up Studio Z, a recording studio with ambitions to be a B-movie studio, too.

The local sheriff decided that the resident long-hair must be up to no good and framed Zappa on a ridiculous pornography charge. Frank spent 10 days in jail and three years on probation "during which I could not violate any traffic laws or be in the company of any woman under twenty-one without the presence of a competent adult." The Cucamonga police confiscated all of his work in that raid and never returned it to him.

Author Barry Miles in his essential biography – simply titled Zappa – summarizes the impact that this episode had on the young artist: "By the time he got out [of jail]," he wrote, "he no longer believed anything the authorities had ever told him. Everything he had been taught at school about the American Way of Life was a lie. He would not be fooled again. He made sure that his pornographic tape was heard by everyone: He remade it time and time again, at least a couple of times on each album, rubbing it in the face of respectable society, making America see itself as it really was: phony; mendacious, shallow and ugly."

Skip ahead to 1985.

Senator Al Gore's daughter brings home a copy of Prince's Purple Rain, and his wife, Tipper, flips her bouffant when she hears "Darling Nikki." According to Zappa, she "rounded up a bunch of her Washington housewife friends, most of whom happened to be married to influential members of the U.S. Senate, and founded the PMRC."

The Parents Music Resource Center's primary goal was a rating system for records similar to that used in the film industry, but Zappa saw the group as an effort to censor artists. The so-called "porn wars" were the cause celebre of 1985, attracting the attention of the nightly news back in the days before the 24-hour news cycle. At the center of it all stood the "Filthy Fifteen," the PMRC's list of most objectionable songs. Black Sabbath and AC/DC made the list, and so did Def Leppard. Even Cyndi Lauper was too dangerous for young ears according to the PMRC, but Zappa wasn't on the list.

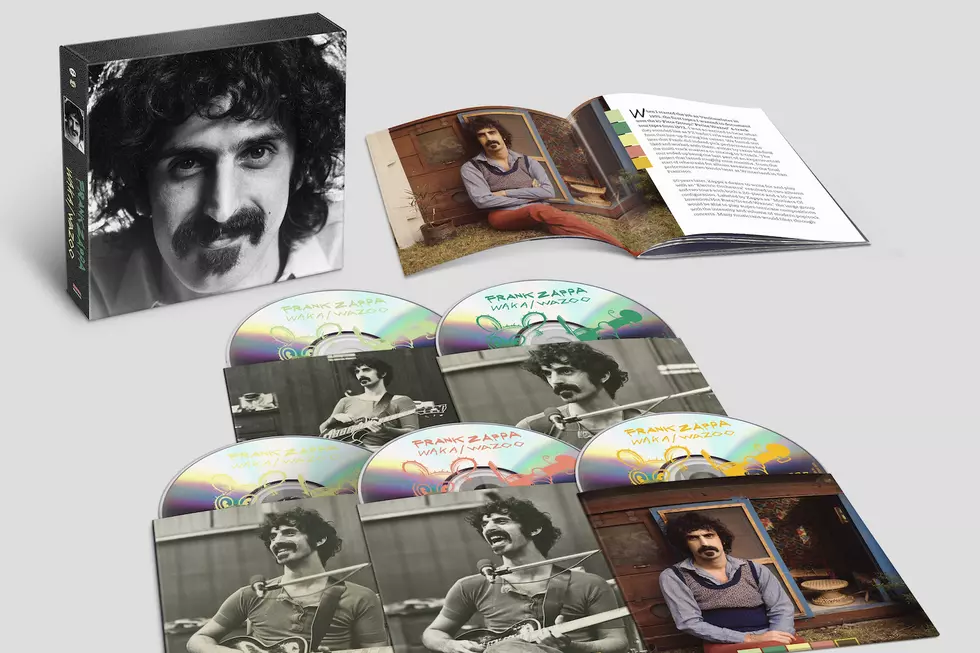

It didn't matter. This was Cucamonga all over again, and Zappa wasn't having any of it. When the PMRC Senate hearings commenced on Sept. 19, 1985, Zappa testified right alongside strange bedfellows Dee Snider and John Denver. Two months later, Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention hit the streets. Its centerpiece on the American edition was the 12-minute "Porn Wars," a sound collage of testimony from the Senate hearing intermingled with Synclavier and some leftover "under the piano" recordings from Lumpy Gravy.

Listen to Frank Zappa's 'I Don't Even Care'

For some, "Porn Wars" is a masterpiece, for others it's self-indulgent and unlistenable. One of the challenges that Zappa faced in his post-Warner Brothers career was that his autonomy left him without an editorial voice – no label or producer to say, "I don't know, Frank, maybe it's a little too long, too on the nose, not quite right for the album." The man was a workaholic, spending hours in his home studio, the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen (UMRK) twiddling knobs, splicing tape and programming Synclavier tracks. Twelve minutes of sped-up Fritz Hollings and future vice-president Al Gore may have been a fine catharsis, and it's a blast for fans of Mothers-era freak out recordings, but if you're looking for something to throw on while rocking down the freeway, "Porn Wars" isn't your best choice.

On the other hand, the aforementioned "I Don't Even Care" is one of the funkiest tracks in the prolific Zappa's catalog. A co-write with Johnny "Guitar" Watson, the track is simple, straight ahead guitar-crunching funk that would have been right at home next to "Apostrophe." For fans of the guitarist's mid-'70s output, dropping the needle on that track must have felt like a long-awaited homecoming, but there's a catch: "I Don't Even Care" didn't appear on the U.S. edition until 1995, when the album was reissued by Rykodisc. It was one of three tracks that replaced "Porn Wars" on the international edition's first release.

The other two are instrumental pieces for Synclavier, the first of which is "One Man, One Vote," which sounds roughly like montage music from a Revenge of the Nerds movie. The other "international" track was "H.R. 2911," which was basically a shortened rewrite of the musical accompaniment to "Porn Wars." "Little Beige Sambo" and "Aerobics in Bondage" round out the album's Synclavier pieces. Some fans love Zappa's synthesizer works, others find them cold and boring. Regardless, next to the dirty groove of "I Don't Even Care" they sound out of place (or vice versa).

This leaves four tracks that fall into the jazz and/or humor categories of the Zappa oeuvre. "We're Turning Again" is a pretty nasty jab at the hippies that were the artist's earliest fans and, according to Miles, perhaps a swipe at his former band mates. "Zappa was still seething at having to part with money in unpaid royalties to the former Mothers of Invention and his anger and resentment seems to have been expressed in [the song]," the author writes.

Bitter and cruel it may be, but that's sort of the point: Nobody messed with Zappa's livelihood without being cut by his sharp tongue.

"Alien Orifice" and "What's New in Baltimore" feature some of the last brilliant Zappa guitar work on record, as he turned more toward serious music and punditry in his later years. "Yo Cats" finds Johnny "Guitar" Watson in lounge lizard mode, mocking union musicians: Watch your watch, play a little flat / Make the session go overtime, that's where it's at. This was yet another thing that Zappa cared deeply about: the primacy of the composer. Dealing with musicians and unions was one of the reasons that Zappa turned to the synthesizer, writing in his memoir that "it allows me to create and record a type of music that is impossible (or too boring) for humans to play."

In a way, Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention is the artist's masterwork. Its weakness, a lack of cohesive style, is also its strength. All of the Frank Zappas are on display: the comedian, the guitar virtuoso, the pedant, the self-indulgent avant garde composer, all while incorporating material spanning the length of his career up to that point. It may not be the favorite album in the Zappa discography, but it is an essential document.

There's a nice footnote to this story. Even after their bitter fight both in the press and on the Senate floor, as Frank Zappa lay dying from prostate cancer, the PMRC's Tipper Gore paid her respects to the great man. Miles quotes Zappa in his biography: "She sent me a sweet letter when she heard I was sick, and I appreciate that."

Parents Music Resource Center's 'Filthy Fifteen'

More From Ultimate Classic Rock