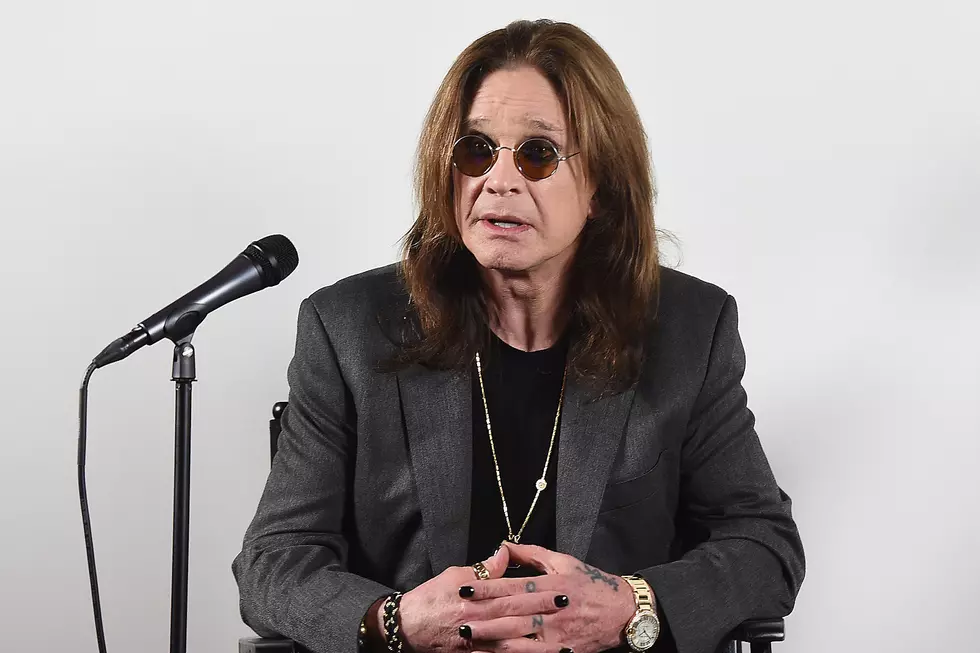

When Bernie Torme Played Ozzy Osbourne’s First Post-Randy Rhoads Shows

There’s a particular type of unsung hero, one who’ll play an essential role in a moment of history, even though that moment will remain invisible because of the scale of the moments around it. You’ll never know he was a hero.

In fact, you might even think he was a villain. But those with the wit and intelligence to read between the lines will spot that kind of hero in the historical accounts – and they almost always have the best stories to tell.

Such a hero is Bernie Torme, who played seven shows with Ozzy Osbourne over a 10-day stint with the band, then left, to be regarded by many as a sell-out, a cash-grabber or even just a failure. The opposite of all those things is true of the Irish guitarist.

Former Black Sabbath vocalist Ozzy was suffering on the road in 1982. The Diary of a Madman tour, supporting the release of his second album, had already featured his notorious bat-biting incident, his collapse on stage, his even more notorious Alamo scandal and a heated disagreement between him and guitarist Randy Rhoads. The singer would later go on to shave off his hair in an attempt to escape his personal torment, while several sets of dates were postponed as he struggled with addiction and depression.

Rhoads was killed on March 19, 1982 during a flight on a small plane. The musicians had loved and respected each other – but they were in disagreement about their future directions when the tragedy struck. Ozzy’s manager and later wife, Sharon Arden, seemed to feel that if Osbourne stopped at that point, he might never return to music. So their thoughts turned to replacing Randy, and they quickly settled on Torme, who’d recently quit Deep Purple singer Ian Gillan’s solo band.

“I’d been on Jet, Don Arden’s label, and I kind of knew Sharon,” Torme told UCR, two years before his death. “I was on the periphery of the family, and I’d just left Ian. They thought, ‘He’s out of a job – he’ll jump at it!’” But he had his own album and tour to work on. “Big artists have a thing where it’s totally incomprehensible that anyone would say ‘no.’ When I was saying, ‘I can’t, I have all this going on,’ David Arden [Don's son] was thinking, ‘He’s probably only saying that to up his price. Typical muso!’”

Bills need to be paid, and so when David offered Torme £2000 a week, and paid a week’s wages in advance, the guitarist agreed to step in – as long as it was only for a month. So he flew out to the U.S. to join a band that included keyboardist Don Airey, bassist Rudy Sarzo and drummer Tommy Aldridge. “When I got there Sharon told me it wasn’t 2,000 pounds a week … it was 200 dollars a week," Torme remembered. "She said, ‘David’s on drugs. He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.’ I said, ‘But I’ve had two grand already!’ She said, ‘Well then, we ain’t going to pay you anything until it’s paid off.’ Start off on the best footing!”

As someone who’s not mainly motivated by money, he was already able to dismiss the moment as funny rather than frustrating; but other parts of the problem weren’t so easy to dismiss. “It was horrible,” Torme said of the emotional situation. “I was out there on the Thursday and Randy had died the previous Saturday. It wasn’t even a week. I don’t think anyone spoke to me the day I arrived, other than Don Airey. It was a really bad atmosphere, and understandably so. I suppose, on some level, Tommy and Don wanted to carry on. Ozzy had no desire and Rudy certainly hadn’t.”

An audition successfully passed, three days of rehearsals took place, and Torme began to realize the lose-lose position he’d got himself into. “Even if I played okay, even if I played a nice solo or whatever, if anyone looked at me on stage they thought, ‘Oh, shit. It isn’t Randy,'" Torme said. "The first show [on April 1, 1982 in Bethlehem, Pa.] was appalling. I didn’t have my amps, my pedals and I had one guitar. There were three or four tracks where we re-tuned and I had to use a hire guitar that was a piece of shit. And apart from anything else, I did not know the songs.

“It was incredibly hard to hear anything on that stage – you had the castle and everything, and all I could hear was the snare drum and Ozzy. I was literally stood at the bottom of Tommy’s pyramid, staring up trying to see when he was hitting things. It was really terrifying.”

And Ozzy? “He was having a really bad time. I’d come off stage and he’d be standing at the back, crying his eyes out. Any day off he was out of his face. He wasn’t able to cope. I think he had a terror because his career has been in complete shit for years, and he’d had a kind of life again because of Randy.

“And again, I had this situation where Sharon and him thought I was just playing hard to get. I was saying, ‘I have to go home in a month – I have this tour booked,’ and they were going, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah.’ Ozzy, underneath his persona, is really insecure, so Sharon was protecting him by saying, ‘Bernie really wants to do it, Ozzy.’”

On reflection, Torme feels it’s likely that he was Don Arden’s pawn in a political game that stretched across the Atlantic, between Jet Records in the U.K. and their U.S. distributors. “By the time we did Madison Square Garden I was fairly okay. I wasn’t by any means playing what Randy played; I wasn’t even able to try. When we got to MSG I kept saying, ‘When’s the sound check?’ They said, ‘Don’t worry about that.’ I didn’t get a sound check – they told me, ‘The record company demanded that we try out Earl Slick!’ I was pissed off about that. I’m here, I’ve carried off these shows, you keep asking me to stay … and then you do that?”

He only met Night Ranger guitarist Brad Gillis - who would go on to take over the guitar slot in Osbourne's band on April 13, after Torme had played just seven shows - by accident. “The American label wanted Brad out, but he wasn’t able to get an audition and he was in the crew coach. In a Holiday Inn I went down for breakfast, and this healthy-looking Californian had a guitar at the table, and he was stunning. He knew all the songs and he’d seen Randy playing. He said, ‘I’m here because the label think you’re going to fuck off.’

“Don Airey was the only person who had any interest in auditioning anyone, so I said, ‘Don, I want to go home. This guy is great. Give him an audition.’ I’d already told Ozzy and Sharon that I was leaving, but that I’d hang on until they found a replacement. Then I discovered they were carrying a replacement but they wouldn’t audition him!”

Torme hung on until Gillis had performed his first show, which the Irishman watched from the crowd. “I would have to say it did not look happy,” he said of seeing the band play without him. “I’d seen a lot of things with the Gillan band, and even when there was an amount of hatred and people being pissed off with each other, it had a kind of a gel. Ozzy’s band didn’t come across like that. It was not a happy bunch of campers.”

He went home the next day, believing that his frontman still had a low opinion of him. “When I’d gone to their hotel suite to say, ‘I’m going to leave,’ Ozzy had looked absolutely flummoxed," Torme added, "Sharon said, ‘It’s because he wants to play a completely different type of music, Ozzy.’ It was protective, and I understand it, so I’d just gawped and said, ‘Yeah!’

“I saw Oz when they did the U.K. tour. Rudy had left and they had Pete Way on bass, and I think Don had left too," Torme said. "We had a laugh, but it was very stressed because there was a massive row in the dressing room between Tommy and Pete. I came away thinking, ‘I’m glad I’m not doing this!’”

Fools rush in where angels fear to tread – although Torme was all too aware of the heaviness of where he’d been, even if he wasn’t able to comprehend it all at the time. “I’d had a problem because I thought, at some point in the show, Oz ought to have said something about Randy’s passing. He didn’t," he said. "For years that really bothered me; but I can see now that he wasn’t able to. If he’d said something he’d have crumbled and crawled off. His onstage persona is incredible, but I don’t think he was able to let that drop at all.”

Torme did receive a fair amount of gratitude, though. “Less so from the band, because they had no interest in being there," he said. "Emotionally, I don’t think they ought to have carried on. But Ozzy had 40 crew and all these people had their families and mortgages hanging on the tour going on. I had all these American giants coming up and saying, ‘Hey man, thank you. You saved my family.’”

Sometimes in life, there’s no right answers. Sometimes it’s all about taking action, just because standing still is the only wrong thing to do. Torme is absolutely clear that, while he’s glad that he did what he did, it will be someone else’s turn if a similar situation should ever arise.

It’s fair to wonder if that someone will do such a great job of braving the emotional turmoil, delivering a passing performance without the essential tools, tolerating the winds of politics howling around him, identifying his own replacement and getting him set into place, then leaving with the knowledge that he’ll never be fully recognized for saving jobs, careers and the future of the then-tarnished icon that was Ozzy Osbourne.

“For years I regretted that I hadn’t met Randy,” said Torme, who died in 2019. “Five or six years ago I met his brother Kelly and had a long chat. There were a lot of things I didn’t know. He was half-Irish; I’d always thought he was pure Yank. That’s a small, tribal thing to say, but it made a difference to me. It helped with the emotional aspect.

“People just don’t understand what it was like," he added. "You get the most inane comments, and people are allowed to say anything, but it was emotionally a terribly hard thing for me. I still have nightmares about it.

“I’m glad I was able to keep people’s wages being paid, but at the same time I think, ‘Would you have done it if you hadn’t been offered two grand a week? You selfish bastard!'" Torme concluded. "But then I think, ‘Ah yes … but I did good.’”

Ozzy Osbourne Albums Ranked

Think You Know Ozzy Osbourne?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock