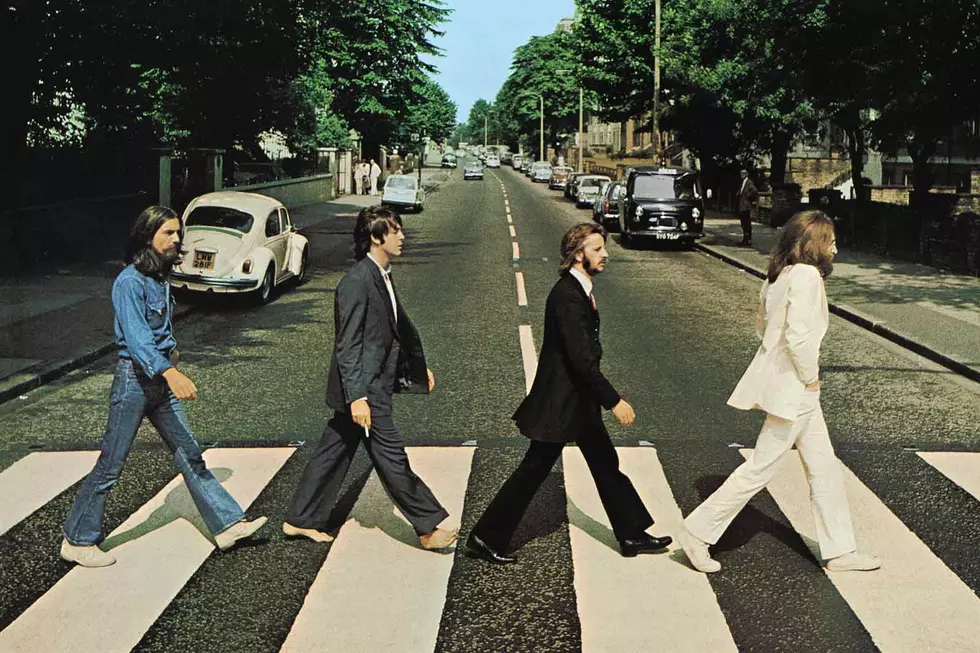

The Story Behind Every Song on the Beatles’ ‘Abbey Road’

The Beatles never meant for Abbey Road to be their last-recorded album together. In fact, John Lennon didn't announce he was leaving until almost a month after the sessions concluded in August 1969.

Yet a sense of finality hung over the project, an elegiac mood that infused even its more rock-focused turns. The Beatles were beat up emotionally, having shelved their last album amid growing internal strife over their business ventures. "The Beatles had gone through so much and for such a long time," producer George Martin said in Anthology. "They'd been incarcerated with each other for nearly a decade, and I was surprised that they had lasted as long as they did."

We all know what happened next. That made it easy to picture the final lyric on the album's Side Two medley as an era-defining sendoff: "And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make." The song's title seemed to say it all: "The End."

Even there, however, the Beatles added an impish coda, tacking on a leftover snippet that brilliantly punctured the self-serious nature of what came before. That moment is a truer representation of what Abbey Road actually was, rather than a Big Statement of Farewell.

They combined recent things with older song fragments, experimented with modern sounds from the just-released Moog synthesizer, and found common musical ground again after trying and initially failing to complete Let It Be. When it arrived on Sept. 26, 1969, Abbey Road was simply the latest thing by the Beatles, a batch of cool new tunes – not a heart-rending goodbye.

We're taking a similarly small-scale approach here, as we tell the story behind every song on the Beatles' Abbey Road.

'COME TOGETHER'

"Come Together" heralds the more song-focused first side on Abbey Road, as Lennon transformed an idea he'd originally written for Timothy Leary's failed gubernatorial campaign against Ronald Reagan. Leary, who was name-checked while attending Lennon's bed-in for peace earlier in the summer, ended up in jail on possession charges. That opened the door for Lennon to take back his song. He originally envisioned it as a Chuck Berry-style rocker, even directly referencing "here come old flat-top" from his 1956 hit "You Can't Catch Me." Paul McCartney suggested they slow things down as a way of differentiating things, leading the way with a swampy, mixed-forward bass line. Unfortunately, that didn't mollify Berry's publisher. Morris Levy sued, saying the two songs were still too similar. They settled out of court, with Lennon agreeing to record a batch of Levy-owned songs that became 1975's covers-focused Rock 'n' Roll.

'SOMETHING'

The original studio version of this George Harrison song ended up stretching to nearly eight minutes, before a four-chord coda led by Lennon at the piano was excised. Lennon later sped up the same pattern to create the foundation on "Remember" for his 1970 solo album Plastic Ono Band. By then, Harrison had scored his first-ever A-side chart-topping single, a sign that the Beatles' other songwriter had officially come into his own. "For the first time," engineer Geoff Emerick later told Music Radar, "John and Paul knew that George had risen to their level." Joe Cocker – who'd already had a U.K. No. 1 hit with the Beatles' "With a Little Help from My Friends" – actually made the first pass at "Something," based on Harrison's original demo. His version wasn't released until after Abbey Road was already on store shelves. "Something" went on to became the second-most covered Beatles tune, after "Yesterday."

'MAXWELL'S SILVER HAMMER'

McCartney was so intent on turning this peppy little number about a homicidal medical student into the Beatles' next single that he basically ran it into the ground. Recording began with 21 grueling takes on the first day; at one point, they spent more than two hours overdubbing guitars. McCartney later sent for an actual blacksmith's anvil, rented from a local theatrical agency, so Ringo Starr could simulate the murders. "I remember George saying, 'You've taken three days, it's only a song,'" McCartney said in Anthology. "'Yeah, but I want to get it right. I've got some thoughts on this one.'" Lennon, who didn't appear on the track, later told David Sheff in All We Are Saying that he hated "Maxwell's Silver Hammer." He wasn't alone. "The worst session ever was 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer,'" Starr told Rolling Stone in 2008. "It was the worst track we ever had to record. It went on for fucking weeks. I thought it was mad."

'OH! DARLING'

McCartney spent days trying to nail this vocal, arriving before the others in an attempt to get the raw-edged attitude he'd brought to earlier rockers. He said he wanted it to sound as if he'd "performing it onstage all week," but the Beatles had long since left the stage. "I remember [McCartney] saying, 'Five years ago I could have done this in a flash' – referring, I suppose, to the days of 'Long Tall Sally' and 'Kansas City,'" engineer Alan Parsons said in Mark Lewisohn's The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions. Lennon later argued that he should have taken over, telling writer David Sheff that his voice would have been more naturally suited to this track. It took almost a month but McCartney eventually got there, adding piano as well. Harrison switched to the bass.

'OCTOPUS'S GARDEN'

Starr's second-ever Beatles original grew out of a tense moment. He temporarily quit the band during sessions for the White Album, borrowing a yacht from Peter Sellers for a family trip to Sardinia. On board, the ship's captain regaled Starr with stories about the local marine life, including the octopus. He began working on this song, with a key assist from Harrison, during the sessions that eventually produced Let It Be. In time, "Octopus's Garden" emerged as a detailed wonder: Harrison played his guitar through a Leslie speaker cabinet to create a distinctive gurgling effect, just as they'd done with Lennon's vocal on "Tomorrow Never Knows." During the solo, the Beatles also used a compressor triggered by a pulsing signal from the Moog's low-frequency oscillator, making it sound as if they were underwater.

'I WANT YOU (SHE'S SO HEAVY)'

A titanic cry of passion, Lennon's "I Want You" was the first Abbey Road song they attempted in the studio, rather than during rehearsals at Apple or Twickenham. He and Harrison almost immediately began multi-tracking their guitars for the outro. "They wanted a massive sound," engineer Jeff Jarratt told Guitar World in 2017, "so they kept tracking and tracking, over and over." In this way, Lennon's song perfectly mirrored his lyric's boiling obsession. He also used the Moog's white-noise generator to create a tornadic wind effect. As "I Want You (She's So Heavy)" built, however, the question of how to end things inevitably arose. "I thought the song was going to have a fade out, but suddenly John told me, 'Cut the tape,'" Emerick told Music Radar. "I was apprehensive at first: We'd never done anything like that. 'Cut the tape?' But he was insistent, and he wound up being right."

'HERE COMES THE SUN'

Harrison had endured a brutal winter marked by the collapse of the Let It Be project, a drug bust and increasingly contentious business meetings; then suddenly the first signs of spring arrived. "'Here Comes the Sun' was written at the time when Apple was getting like school, where we had to go and be businessmen: 'Sign this' and 'sign that,'" Harrison said in his autobiography I Me Mine. "So, one day I decided I was going to sag off Apple and I went over to Eric Clapton's house. The relief of not having to go and see all those dopey accountants was wonderful, and I walked around the garden with one of Eric's acoustic guitars and wrote 'Here Comes the Sun.'" They'd grown close over the previous months, as Clapton sat in on "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" and Harrison returned the favor on Cream's hit "Badge." Harrison completed that skeletal arrangement with more sounds from the then-new Moog synthesizer; Lennon, who was recovering from a car accident, isn't featured on this song.

'BECAUSE'

The last of the Abbey Road songs to make significant use of the Moog -- after "Maxwell's Silver Hammer," "I Want You (She's So Heavy)" and "Here Comes the Sun" -- "Because" was also the last tune recorded for the album. Harrison had the enormous machine specially made, then everyone began trying to make it work. "I don't think even [the late inventor] Mr. [Robert] Moog knew how to get music out of it," Harrison said in Anthology, admitting that at first "it was more of a technical thing." "Because" was inspired by Lennon's wife Yoko Ono, a classically trained pianist. She was playing Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 14 – known as the "Moonlight Sonata" – when Lennon wondered if he could reverse the chords to create something new. Lennon, McCartney and Harrison then sang a three-part harmony – three separate times, for a total of nine Beatles voices. Producer Martin added a harpsichord, which McCartney now has set up in his personal studio.

'YOU NEVER GIVE ME YOUR MONEY'

McCartney kicks off the Side Two medley by directly referencing the quickly unraveling Apple empire, as business manager Allen Klein and attorney John Eastman struggled for control of the group. "'Funny paper,' that's what we get," Harrison later groused. "We get bits of paper saying how much is earned and what this and that is, but we never actually get it in pounds, shillings and pence." The Beatles constructed "You Never Give Me Your Money" using parts of unfinished songs, just as they had with 1968's "Happiness Is a Warm Gun." Eastman eventually became McCartney's father-in-law, but the Beatles' legal and financial issues dragged on into the '70s. That gave added weight to this lament, which McCartney eventually admitted was "me directly lambasting Allen Klein's attitude to us — all promises, and it never works out." McCartney would return to the topic one more time on Abbey Road, later in the medley.

'SUN KING'

"Sun King" started with a Fleetwood Mac-ish guitar signature – Harrison cited the then-new "Albatross" as an inspiration – before Lennon began singing something best described as a delightful combination of Spanish, Italian and Portuguese-inspired nonsense. There's a reason, actually: "Sun King" was said to have come to Lennon in a dream. (One actual phrase jumps out: "Chicka ferdi," Lennon subsequently confirmed, was "a Liverpool expression; it doesn't mean anything, just like 'ha ha ha.'") Though "Sun King" was also an unfinished recording, it was recorded back-to-back with "Mean Mr. Mustard" as the newly energized Beatles rebounded after Let It Be. "The second side is brilliant," Starr later enthused. "Out of the ashes of all that madness, that last section is for me one of the finest pieces we put together."

'MEAN MR. MUSTARD'

The first of two Lennon songs originally demoed at George Harrison's house in May 1968, "Mean Mr. Mustard" underwent one major edit in the interim. As the Side Two medley began to take shape, Lennon changed one character's name so that the song would flow more smoothly into the succeeding "Polythene Pam." "We juggled them about until it made vague sense," Lennon said in Anthology. "In 'Mean Mr. Mustard,' I said 'his sister Pam' – originally it was 'his sister Shirley' in the lyric. I changed it to 'Pam' to make it sound like it had something to do with it." He had initially been inspired by a newspaper story about a cheapskate who hid his money – only instead of up his nose (as the song says), it was in his rectum. Lennon was famously cool to the idea of the multi-song medley on Abbey Road, but eccentric moments like this one give the song cycle a fizzy propulsion.

'POLYTHENE PAM'

Lennon's nostalgic, humorously perverted "Polythene Pam" was recorded at the same time as McCartney's "She Came in Through the Bathroom Window" – the only instance where they directly linked two separate originals. Lennon drew upon a couple of different oddball characters from the band's past, returning to both the Scouse accent of the Beatles' early days and their career-making exclamation "yeah, yeah, yeah." The song's fast pace and a difficult transition to the next cut made it particularly difficult to accomplish a clean run-through. Starr ended up re-dubbing his rhythm part in an effort to get it just right. McCartney also had an audible bass flub, but everyone decided to leave it in. "At one point, he overshot the note on one of his glissandos," Emerick said in Here, There and Everywhere. "Instinctively, he said, 'Oops, let me drop that in and fix it,' but we all spontaneously overruled him, saying, 'No, it's great! Leave it in.'"

'SHE CAME IN THROUGH THE BATHROOM WINDOW'

When you're Paul McCartney, things like this actually happen. "She Came in Through the Bathroom Window" was sparked by an incident with an overzealous fan who took a ladder from his garden and climbed into his home on London's Cavendish Avenue. But she wasn't the only one who attempted to gain entry. Neighbors began to report these break-ins, inspiring McCartney to write: "Sunday's on the phone to Monday, Tuesday's on the phone to me." The rest of it? Well, gibberish, really. But fun. He also threw in a reference to the strip clubs on the Reeperbahn in Hamburg, where the Beatles were in residence before becoming famous. McCartney completed the narrative while in New York City to formally announce Apple Corps., after spying a law-enforcement officer's ID ("So I quit the police department ... "). Joe Cocker made a run into the Top 40 with a cover of this one too.

'GOLDEN SLUMBERS'

The genesis of "Golden Slumbers" goes back further -- much further. Like, centuries earlier. McCartney was visiting his father's home and saw sheet music for a ballad by Thomas Dekker, an Elizabethan poet and dramatist. McCartney combined the lyric – after a few small edits – with an original tune, then recorded the piece as one with "Carry That Weight." "I liked the words so much," he told Barry Miles in Many Years From Now. "I thought it was very restful, a very beautiful lullaby, but I couldn't read the melody, not being able to read music. So, I just took the words and wrote my own music. I didn't know at the time it was 400 years old." Harrison again switched to bass, since McCartney was at the piano. (Lennon was still recovering from his car accident.) Nowhere was the difficulty of this period more emotionally dealt with, as McCartney seemed to mourn the Beatles' lost innocence to a swell of Martin-directed strings: "Once there was a way to get back homeward."

'CARRY THAT WEIGHT'

Everything was heavy at this point, in particular the day-to-day operations at Apple. "That's what 'Carry That Weight' was about," McCartney told writer Barry Miles. "In this heaviness, there was no place to be. It was serious, paranoid heaviness and it was just very uncomfortable." Martin and McCartney add a call back to "You Never Give Me Your Money," which kicked off the Side Two medley, by returning to a brass-led version of the melody with different lyrics. Later, the song's closing guitar notes help bridge "Carry That Weight" and "The End." But not before Abbey Road reveals its darkest moments. "I'm generally quite upbeat," McCartney subsequently admitted, "but at certain times things get to me so much that I just can't be upbeat anymore, and that was one of those times. 'Carry that weight a long time' — like forever!"

'THE END'

"Carry That Weight" featured an unusual four-part harmony. "The End" took things one step further, allowing each of the Beatles – even the typically reluctant Ringo Starr – their turn in the spotlight. ("Solos have never interested me," Starr said in Anthology. "That drum solo is still the only one I've done.") After a brainstorming session, McCartney, Harrison and then Lennon took turns on lead guitar, performing two-bar solos over backing vocals singing "love you, love you." It brought everything full circle. "Hearing that performance was unbelievable – and it was all done live and in one take," Emerick told Guitar World. "When they were finished, everyone beamed. I think in their minds they went back to their youth and all those great memories of working together as a band." They then came to an abrupt halt for McCartney's love-you-make prescription, as Martin's swelling strings brought Abbey Road to a dramatic close.

'HER MAJESTY'

A 23-second acoustic goof, "Her Majesty" was originally situated between "Mean Mr. Mustard" and "Polythene Pam" in the Abbey Road medley, before McCartney changed his mind. A tape-operator decided to place "Her Majesty" after a length of empty tape following "The End," in a safe-keeping move, and everyone agreed this happy accident made the perfect album postscript. "It was quite funny because it's basically monarchist, with a mildly disrespectful tone – but it's very tongue-in-cheek," McCartney said in Many Years From Now. "It's almost like a love song to the Queen." He first brought "Her Majesty" out during January sessions for Let It Be; Lennon memorably joined him on slide guitar for a subsequent run-through in Twickenham. McCartney ended up recording the finished version live with only an acoustic guitar, before the Beatles started on "Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight."

Beatles’ ‘Sgt. Pepper’s’ Cover Art: A Guide to Who’s Who

You Think You Know the Beatles?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock