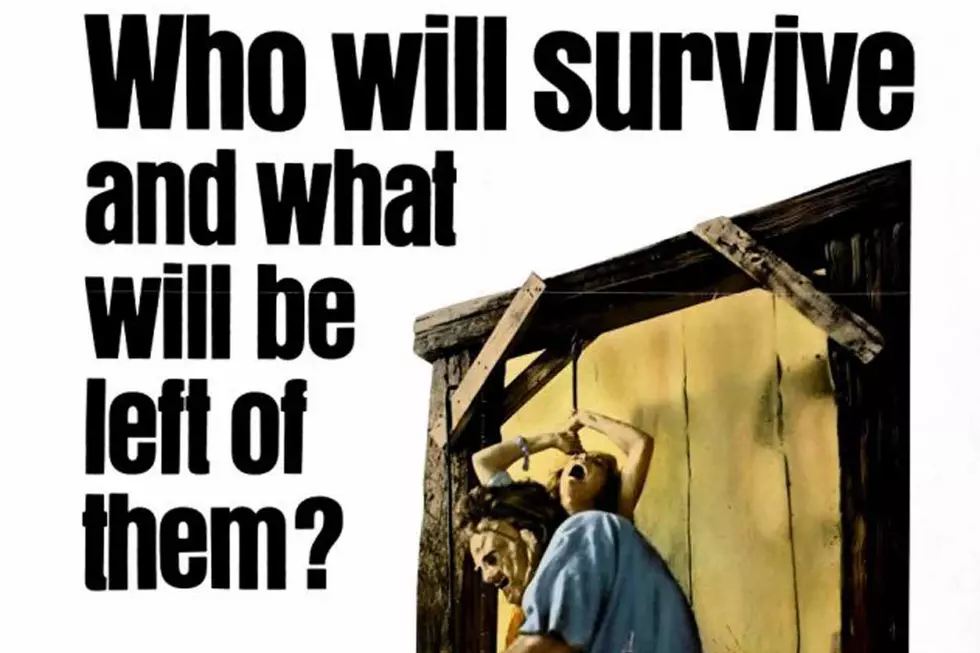

45 Years Ago: ‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’ Scares the Hell Out of Everyone

If you wanted to make the argument that The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is the greatest horror movie of all time, that argument might go something like this.

On the technical side of things, it's nearly flawless. It sets precedents, small and large, that are still routinely followed by scary movies. It has a devastating sense of humor, and it manages to suggest a scathing social commentary without being heavy-handed. And its small budget enhances rather than detracts from its fear, and despite its formidable reputation, it relies on a surprisingly low level of blood and gore.

Most importantly, it feels as much like an actual descent into nightmare as any film ever made.

The plot of the movie -- which was released on Oct. 1, 1974 -- is deceptively simple and also perfectly constructed to slowly and inexorably move the viewer from the real world into this nightmare. A group of five young people is on a day trip through the Texas countryside. Someone has been desecrating graveyards, and the two main characters – Sally (Marilyn Burns) and her wheelchair-bound brother Franklin (Paul A. Partain) – want to make sure that their grandparents' resting places haven't been disturbed.

After stopping at the graveyard, they decide to visit an abandoned house their family once owned. On the way, they have two encounters.

First, they pick up a hitchhiker (played by Edwin Neal) who's about their age but obviously comes from a far different background. While they seem well-adjusted and ordinary, he's strange, has a large birthmark on his face and is from a family that used to work at a nearby slaughterhouse. At first fascinated by him, the group soon becomes repelled. When he cuts his hand with a pocket knife, takes a Polaroid of them that he burns as they're driving and then playfully slashes Franklin's arm with a razor, they kick him out and leave him on the side of the road.

The second encounter involves a stop at a small gas station and barbecue joint. The station is out of gas because the tanker truck hasn't shown up yet, so the kids decide to go visit the family house and then return to fill up the van. They do this even though the slightly unhinged man who owns the station (Jim Siedow) warns them that they probably don't want to go up there.

At the house, they poke around for a while and then slowly separate. Two of the group – Kirk (William Vail) and Pam (Teri McMinn) – wander down to look for a swimming hole. They hear the sound of a generator from a nearby house and walk over to ask to borrow gas.

It's at this point that the disturbing tone the film has set up takes a sudden turn into violence.

The kids are, one after another, killed by a large man known as Leatherface (Gunnar Hanson) who wears a mask made of human skin. Sally alone survives, only to stumble into the macabre truth.

The hitchhiker, the man who runs the gas station and Leatherface are all members of a family that used to support itself by working at the slaughterhouse until modern methods of killing rendered them unemployable. They now live with their near-mummified grandfather (John Duggan) in a house festooned with human and animal bones; it seems clear that the barbecue they serve, and which the kids ate when they stopped at the gas station, is, in part at least, made from humans.

The extreme visceral force of the movie is developed in a number of ways. There's little visible blood, in part because director Tobe Hooper thought that by taking that tact the film may get a PG rating; instead it was viewed as so violent and offensive that it was banned in many countries. Even though The Texas Chain Saw Massacre eschews onscreen splatter, it embraces the actuality of death – twitching bodies, human pain as a reality rather than a titillation for the audience – in a way many horror films don't.

Hooper also does a masterful job of creating tension and using the camera as a vehicle for edging the viewer into a state of fearful anxiety, in much the same way Edgar Allan Poe did with language. From his subtle use of dolly shots to his ghastly use of foreground and background to show Leatherface cutting up a body while a girl dangles from a meat hook to his use of close-ups of the murderous men's faces that put us in Sally's point of view in the climactic scene, Hooper continually maximizes the potential of the medium.

The low budget helps him in this. Shot on 16mm by cinematographer Daniel Pearl, the film feels raw and almost documentary-like in its graininess, without any overly produced glossiness that can actually help viewers remember that they're only watching a movie.

Similarly, the archetypal patterns of the film make it feel unconstructed rather than imitative. It's one of the earliest horror movies to feature what would become called that "final girl" trope, in which the heroine is the only one to survive. It's also one of the first films to feature a killer with a signature weapon: Leatherface's chainsaw. And even though the cinematic idea of a villain hiding his face goes back at least as far as Lon Cheney's Phantom of the Opera (1925), Leatherface's mask sets the template for numerous subsequent slasher movies.

Watch 'The Texas Chain Saw Massacre' Trailer

But perhaps the deepest source of the movie's power comes from its presentation of its family of maniacs. Unlike many of the horror-movie killers he would inspire, Leatherface is not a mindless automaton. He is clearly human.

One of the film's greatest moments comes after he's killed his first two victims. Distraught and confused, he sits in a chair by a window and tries to figure out what to do. Because he's not capably of speech, this is captured in a remarkable moment of physical acting by Hanson. Leatherface is not upset by the killing, it becomes retrospectively clear; he's upset because he's going to get yelled at by his family for making a mess of things. And indeed, later on he gets yelled at because as he was chasing one of the kids, he had to chainsaw down the front door of the house.

The movie casts the slaughterhouse family as having actual, recognizable dynamics: They are an insane version of an American nuclear family. And this is where the importance of the movie's references to the slaughterhouse come in. While the kids who are killed are middle-class people, the family that kills them is their dark, lurid, underclass reflection. They are the people who do the terrible jobs that keep the rest of us fed and clothed, thrown out of work by the vast economic forces of modernization. One of the most shocking suggestions of the film is that it is this social dislocation that has brought out the most taboo elements – grave-robbing, murder, cannibalism – of what is still a recognizable human psyche.

In the end, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is terrifying because it presents its madness as an aspect of humanity, rather than as something alien. It's certainly not for everyone. But in its importance to the genre as well as its impact on moviegoers and subsequent filmmakers, it's one of the best horror movies ever made.

The Best Rock Movie From Every Year: 1955-2018

More From Ultimate Classic Rock