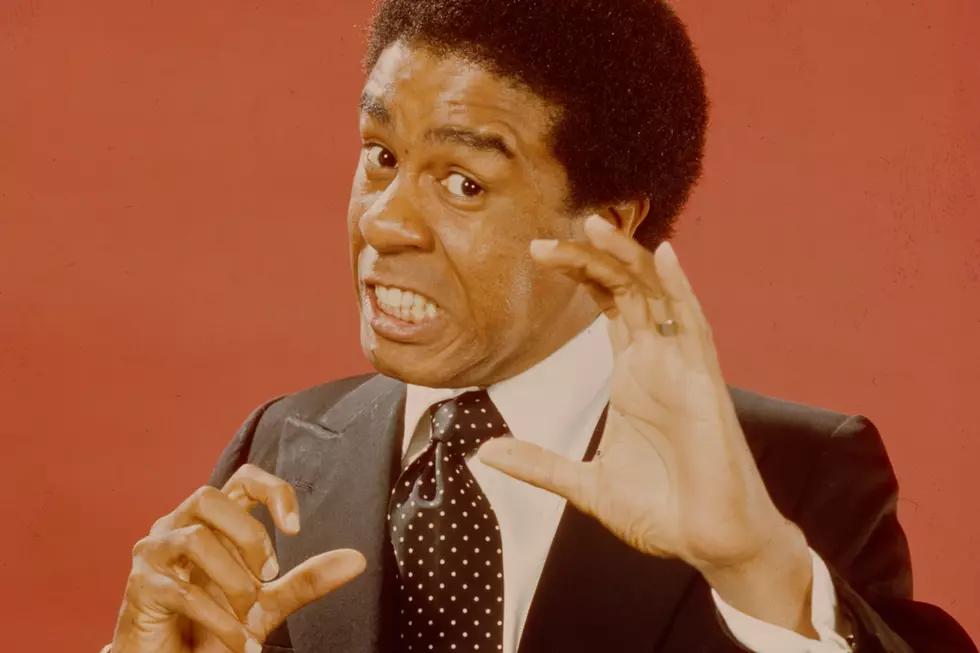

45 Years Ago: ‘The Richard Pryor Show’ Begins Its Brief Run

Richard Pryor’s now-legendary 1975 hosting stint on the brand new Saturday Night Live offered up plenty of evidence as to why NBC would never give the brilliant and volatile stand-up comedian a sketch comedy show. Then, two years later, they did anyway.

The Richard Pryor Show started as The Richard Pryor Special?, a one-shot sketch and variety broadcast that aired on May 5, 1977. Pryor, having won an Emmy as part of the writing staff for Lily Tomlin’s 1973 CBS special, Lily, made similar use of the sketch template, offering a sly deconstruction of the traditionally glitzy, kitschy celebrity variety hour. Dressed in a tuxedo on his way to deliver his network-approved monologue, Pryor is waylaid by a series of loquacious oddballs (played by notable Black character actors Glynn Turman, Shirley Hemphill and LaWanda Page), all of whom spur Pryor to daydream of the comic premises he’d presumably like to be doing instead.

And what Pryor wanted to do was shake things up. The cold open for his first-ever network special saw Pryor as just one of the dozens of shirtless Black men being whipped on a slave ship (by a cameoing John Belushi), with Pryor eventually being singled out for the worst punishment imaginable: to work for NBC. The sketches that follow allow Pryor to do some outsized character work (in a lavish takedown of flamboyant religious grifters), parody current events (Pryor dons a military uniform to provide an NBC rebuttal from notorious Ugandan dictator Idi Amin) and indulge his love for playing cantankerously wise old Black men (double work allows Pryor to get a shoeshine and lecture from himself).

There’s even a spin on the requisite musical act, as Pryor, after promising one insistent fan an appearance by the Pips (without frontwoman Gladys Knight), booked the three-person backup singers to perform just their parts of several songs.

Not all of the sketches hit, as the small writing staff included not only Pryor and lifelong creative partner Paul Mooney, but some more experienced (and white) TV writers (including Alan Thicke, of all people) whose takes, one suspects, account for some of the more familiar material. (Jokes about Idi Amin eating his enemies were late-night monologue fodder at that point.) Still, Pryor and Mooney went into this prime-time venture ready to open some eyes, both by bringing in more Black faces than prime time was used to and by defiantly stretching the sketch form with stylistic boldness.

The show included a poetic interlude featuring gorgeously dressed Black women of various skin tones reciting Langston Hughes’ rapturous ode to Black beauty, “Harlem Sweeties.” Hughes’ authorship is never referenced in the piece, leaving the uninitiated undoubtedly baffled, and signaling that Pryor’s special wasn’t going to concern itself with slowing down so as not to lose anyone. A pair of unsupervised little boys accost Pryor backstage to complain about his stereotypical plans for youth-focused sketches (clowns, athlete cameos), with one precociously lecturing, “You have a unique vehicle here, Mr. Pryor, and we think you should use it as a forum for meaningful expression.” “Take advantage of the medium and conceptualize,” advises the other, leading to Pryor conjuring up a vision of a militantly inclusive Sesame Street-style children’s show, with a multicultural child cast singing an anthem extolling the overlooked historical places of everyone from Sacagawea to Crispus Attucks. With Pryor nowhere to be found in the sketch, it’s safe to say that The Richard Pryor Special? indeed took advantage of the medium to conceptualize.

But the centerpiece sketch is the true masterpiece, starting as a crowd-pleasing piece (pulled partly from Pryor’s 1974 album That N------’s Crazy) about a boastful drunk at a neighborhood bar (manned by Belushi’s bat-wielding, seen-it-all barkeep). Pryor is hilarious, alternately berating and buttering up his fellow barflies before being beaten up and staggering drunkenly across the street to his apartment and his long-suffering wife — played by legendary author and civil rights pioneer Maya Angelou.

The back half of the sketch is all Angelou’s, her emotional and poetically virtuosic lament over the state of her passed-out husband framing Pryor’s already telling knockabout comedy of drunken dissipation as a tragic love story where a good man’s experiences with a racist and unjust world have broken them both. What 1977 audiences made of this pivot to lyrical, played-straight drama by one of the country’s most acclaimed writers is a matter of speculation. (Just to note that the highest-rated shows of the day were Laverne & Shirley, Happy Days and Three’s Company.)

Watch a Clip From 'The Richard Pryor Show'

It’s also up for debate why NBC sought Pryor for an ongoing sketch series. The Richard Pryor Special? had done well enough in the ratings and with critics, but both Pryor’s volatile reputation both on- and offstage and the special’s content made the prospect a risky one. Still, on Sept. 13, 1977, The Richard Pryor Show aired its first episode. That the show ended on Oct. 20, 1977, after only four episodes isn’t surprising. That the show was aired in the first place sort of is.

In the 2004 DVD box set (which includes all four episodes plus The Richard Pryor Special?), an unaired stand-up set saw Pryor refuting any idea he’d been canceled, claiming, “The motherfuckers didn’t cancel me — we were only supposed to do four shows and that’s it. I’m getting my ass out of here.” Sources suggest that 10 episodes were originally contracted for, but, regardless, Pryor’s inevitable battles with the network pegged the over/under for The Richard Pryor Show’s life expectancy at right around the four-episode mark.

Assembling a larger writing staff led by Mooney (Pryor receives a “special material by” credit), and an in-retrospect ridiculously stacked supporting cast (Robin Williams, Sandra Bernhard, Tim Reid, Marsha Warfield, John Witherspoon, Thalmus Rasulala, Edie McClurg, Johnny Yune and Putney Swope’s Arnold Johnson among them), Pryor continued the special’s mission of kicking against the supposed limits of network comedy. Pryor lost his first fight against network notes in the never-aired cold open to Episode 1, where Pryor originally intended to come out nude, reassuring his fans that working for NBC wouldn’t cost him a single thing — before it's revealed that his exposed crotch is as smooth and emasculated as a Ken doll. (The cold open is included on the DVDs, serving as each episode’s menu screen.)

The four episodes that followed are like a glimpse into an alternative TV America where Black voices are in charge of network programming. (In that way, it’s akin to groundbreaking public television series Soul!, where dapper host Ellis Haizlip was as likely to feature the poetry of Nikki Giovanni or an interview with James Baldwin as to throw musical performances by the Jackson 5 or Al Green.) Like the special, not all the sketches are gold; there’s still an occasional whiff of sentimentality or broadness that would have slotted right into the elbow-in-the-ribs chumminess of The Dean Martin Show. But more often than not, when The Richard Pryor Show misfires, it’s due to ambition. And when a sketch hits, it leaves the indelible marks of a show far, far ahead of its time.

A sketch in which Pryor is America’s first Black president not only anticipates Fox News’ carefully engineered undermining of Barack Obama but tosses in a reference to the lack of Black quarterbacks, coaches and owners in the NFL. A fourth-episode sketch set in a gun store looks like it’s headed for tiresome cliche when Pryor’s timid shopper is confronted by a Travis Bickle look-alike but quickly becomes profoundly chilling, as each firearm, when handled by Pryor, tells its inevitably bloody backstory. A shotgun hints in a Southern accent that it was responsible for murdering Freedom Summer activists, while an offscreen Robin Williams adopts an icy precision to brag about his rifle’s human-killing expertise, and Tim Reid’s pistol weeps uncontrollably, crying, “I don’t want to be a gun!” as it becomes clear it was used in the accidental shooting of a child. Asked by the owner if he sees anything he likes, the rattled Pryor stammers out that he does not before fleeing.

Meanwhile, The Richard Pryor Show takes the time to set up sketches that have the patience to set up and pay off a premise - the opposite of SNL's traditional quick-hit sketch pacing. Two WWII veterans’ visit to a Black-owned nightclub turns into an extended showcase for lovingly kitted-out Black performers to dance and sing at length, Pryor and Rasulala’s doughboys content to sit in rapt attention. When Pryor’s intent to propose to his childhood crush turned show-stopping burlesque performer Satin Doll (a stunning Paul Kelly) is thwarted by his realization that her slick manager is also her husband, the sketch ends in rueful but affectionate melancholy, the entire piece coming off like an episode from a lost, Black-fronted omnibus drama series like Playhouse 90. Even a show-opening action sequence like “Black Samurai” is staged like a Kurosawa fight scene rather than Belushi’s then-famous comedic Saturday Night Live samurai, Pryor’s choreographed besting of a small army of robed fighters played completely straight — until the victorious Pryor asks a female bystander, “How was that, mama?”

Throughout the show’s brief run, we see Pryor chafing against the restrictions of his network bosses. Episode 3 opens with a reference to Pryor being put on tape delay on SNL, the comic’s increasingly furious monologue playing out in animated pantomime while a network-censored dubbed voice assures everyone of how much Pryor loves working there. Later in the episode, Pryor notes that a reassuring stand-up segment was ordered by NBC since viewers “see Black people and they get nervous.”

However, if a fourth-episode roast of Pryor was intended to evoke Dean Martin once again, the expansive resulting segment is anything but comforting to prime-time America, with otherwise little-used side players like Williams, Bernhard, Witherspoon, and Warfield allowed a few minutes each to do some harder-hitting material at their boss’ expense. (Bernhard’s line about Pryor giving his kids everything “including a flat nose and big lips” is perhaps the most controversial.)

Watch a Clip From 'The Richard Pryor Show'

Backstage battles aside, the material that Pryor and his writers did manage to put on NBC’s airwaves is bold enough. Pryor’s mission to spotlight those traditionally shut out of mainstream TV saw him booking Native American stand-up Charlie Hill to do a strong five minutes, while comic Al Alen Peterson reprised an earlier SNL guest bit where his macho construction worker does a defiant striptease - right down to bra, panties and a long blond wig - while crooning “I’ve Gotta Be Me.” Some pieces are experimental to the point of revolutionary, as when a silly Richard-as-Little-Richard bit is signal-interrupted by a confessional reverie of a young woman relating her first lesbian experience. Episode 3’s “Ward 8” found Pryor, Rod Serling-like, noting that we all end up in the titular psychiatric ward sooner or later, with cast members taking turns acting out traditional American roles (cop, consumer, housewife, actress) in increasingly manic desperation. And future Roger Rabbit Charles Fleischer makes his one appearance as the severed but still living head that Pryor keeps in a birdcage in his backstage dressing room. When the expected rug-pull or punchline never comes, these sketches are left lingering in the mind precisely like regular sketch comedy doesn’t.

Pryor and Mooney being in the driver’s seat, race is naturally a major theme. A To Kill a Mockingbird courtroom sketch gives Williams his juiciest role as the Jewish lawyer attempting to save his framed-for-rape Black client from hanging. He succeeds (thanks to the witness being too farcically phony even for the all-white jury) but is himself taken out for execution, the foreman explaining how the actions of the “pinko Jew-boy lawyer” might set a bad example for Black citizens expecting regular justice. A lifeboat sketch saw Pryor’s accommodating Titanic steward duly rescuing a gaggle of racist white passengers, all of whom greet his efforts with literally every (uncensored) racial slur in their arsenal. Broad though they are, sketches that put white racism in such bald and unsoftened language earned the show and NBC no end of outraged complaints from viewers.

The Richard Pryor Show wound up ranking 86th (out of 104 shows) in the 1977-78 network TV season, an unsurprising fate considering both the content and NBC’s unwillingness to go to bat for Pryor and his team with committed marketing. (The series aired during the so-called “family hour” instituted by the FCC in 1975, with The Richard Pryor Show’s flaunting of the vague and unenforceable rules on family-friendly programming one of the final nails in that experiment’s coffin.) But anyone looking for precursors to later acclaimed, boundary-pushing sketch series like The Chappelle Show or Key and Peele will discover a little-known but undeniable inspiration in Pryor’s brave, ultimately doomed foray into network sketch comedy.

Rock's 60 Biggest 'Saturday Night Live' Performances

More From Ultimate Classic Rock